Over the last few months I’ve been working on a pilot project that looks at how NCDHC staff have portrayed women through metadata (the information that accompanies the images on DigitalNC) over time. This is a small step towards finding unconscious bias in our work and making our metadata more equitable. I’ve accumulated some interesting examples, and I thought I’d share them here.

Anyone who’s ever tried to trace a matrilineal line knows the frustration of women being referred to only in the context of marriage. This was the convention in historic American culture – you’ll see it in newspapers, books, correspondence – and special collections are no exception. It was pretty easy for me to start looking at bias in our metadata with a simple search on Mrs., which netted me over 2,000 results.

If you browse that search yourself, you’ll see how many records don’t include the woman’s first name. The information that’s been written on or passed down with a photograph often inherited that cultural bias towards a woman’s married state. When NCDHC staff set out to describe a photograph, if all we have is “Mrs. Lewis Dellinger” then that’s what gets transferred to our metadata. Even if we had time to do research to try to locate Mrs. Lewis Dellinger’s given name, in most cases we couldn’t be positive it was the correct identification. So there are a lot of records that can’t be improved given the reliable information we have on hand.

Still, after browsing through DigitalNC, I started seeing places where a simple and quick change could make a difference. Here’s one example:

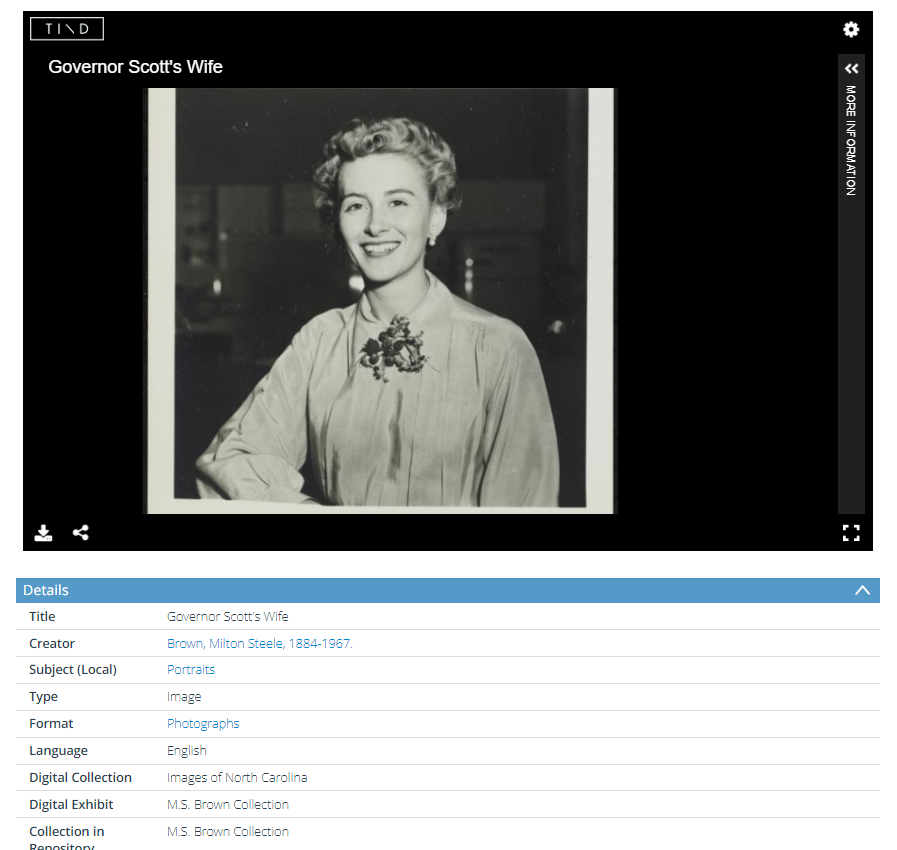

A screenshot of how this record looked initially, with the photograph entitled “Governor Scott’s Wife.”

Unlike many individuals in our collection, I knew this woman’s name and identity would be easy to confirm. Jessie Rae Osborne Scott was a graduate of what is now UNC-Greensboro. She taught high school, helped run a farm, raised five children, and was active in a number of charities and social causes. Other verified photographs of her are available online because she also happened to marry a governor. That fact is notable, but I’ve amended the record so that her own name is foremost while retaining the information originally included with the photograph in the description.

When I first searched our website for the word “wife” I received 221 results; “husband” yielded 54. Because of ingrained bias, even if a woman’s name is available in the metadata her relationship to the man or men in the picture is privileged instead. Conversely, unless the woman was particularly well known or the overt focus of a photograph, husbands aren’t named as such. Here’s an example:

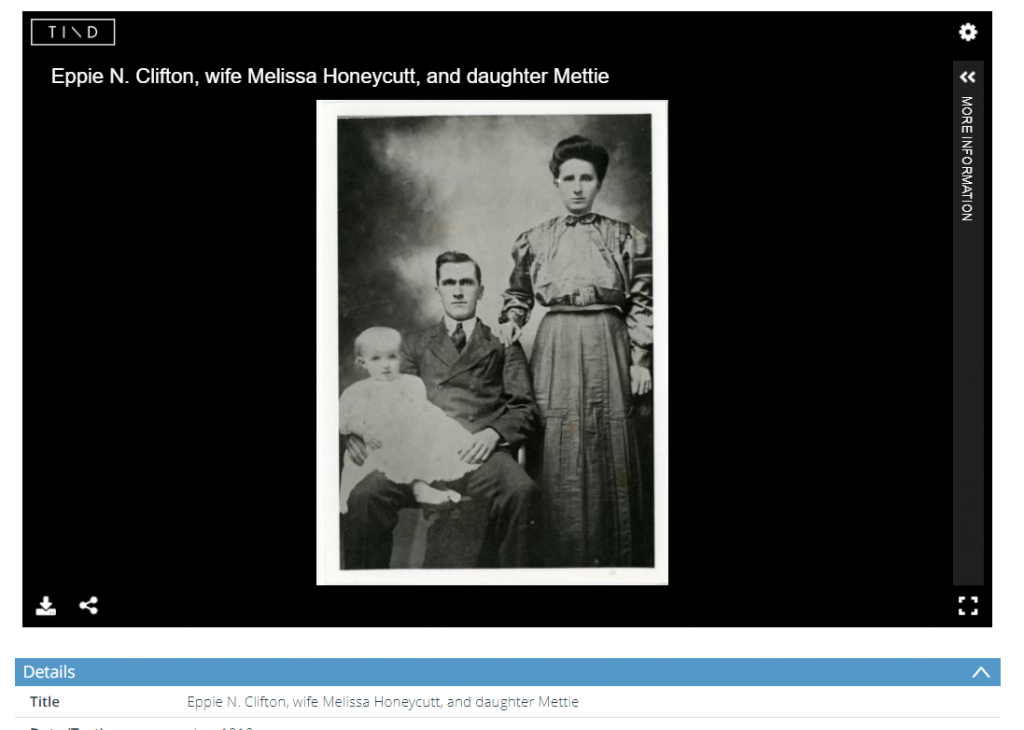

This photograph is entitled “Eppie N. Clifton, wife Melissa Honeycutt, and daughter Mettie.”

Note that the man is mentioned first, and the woman and child are described in relation to him. Here’s how I amended the photo’s metadata:

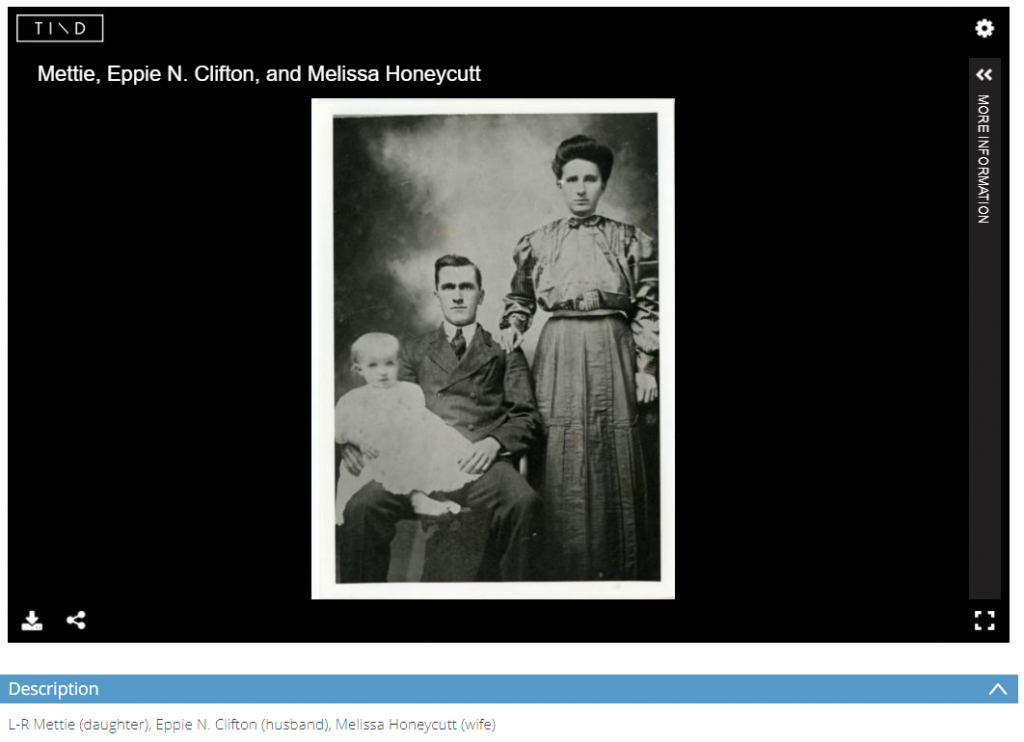

This photograph is entitled “Mettie, Eppie N. Clifton, and Melissa Honeycutt.” The Description reads “L-R Mettie (daughter), Eppie N. Clifton (husband), and Melissa Honeycutt (wife).”

In the updated version I’m just going left to right and taking each person in turn, communicating what was written on or with the photograph. Their family relationship is still given, so that information isn’t lost, but it’s recorded in a way that’s more equal across the group.

Here’s another example I found interesting:

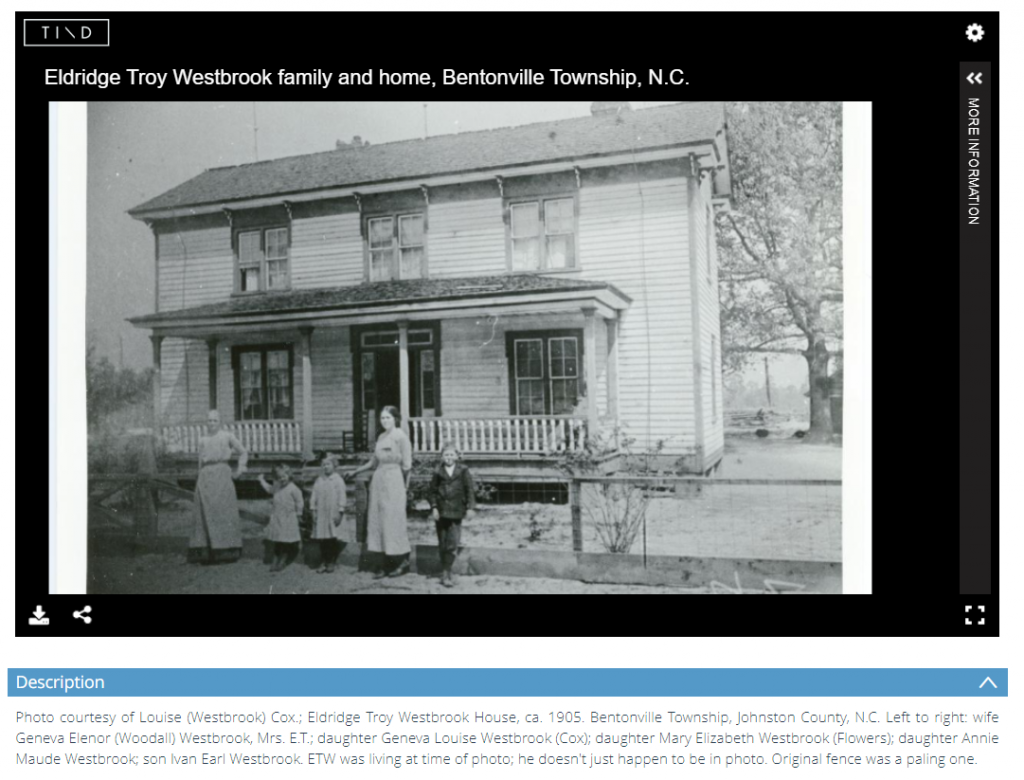

This photo is entitled “Eldridge Troy Westbrook family and home, Bentonville Township, N.C.”

Note that the house is named after the male head of household and his name is noted in the title, but he isn’t in the photo. (The original description we were given even mentions that “ETW was living at time of photo; he doesn’t just happen to be in photo.”) I don’t want to remove the entire name of the house – it might have been identified that way among those who lived in the area – but I can easily improve the equity shown to the individuals who are actually shown in the photo without losing any important information. See what you think. All I did was keep the surname, and move the male’s name down to the description. I also put the familial relationships in parentheses instead of having them precede each name. I think this might subtly shift how people see this photograph and those pictured within. To me they seem less like they’re just hanging around waiting for ETW to arrive.

To sum it up, here are the types of changes we will regularly make to help improve the equity of our metadata:

- We’ll note the full known identity of all of the photograph’s subjects in the title, moving from left to right, as in the example above.

- When a couple’s only known information is a surname, we’ll record the honorifics for individuals from left to right. (In other words, we won’t default to always placing Mr. first.) Example: Mrs. and Mr. Detweiler

- If a familial relationship is recorded about those in the photograph, we’ll note that in parentheses within the description. We’ll give equal consideration to noting relationships of all genders.

Why is this work worth doing? How we name things influences power. It changes who gets noticed in a crowd. It shifts who gets resources when they’re scarce. Every individual has a right to their own identity; we don’t believe that the fact that a woman who lived in a time when she was considered secondary because of her gender should endure the same condition today. Why should we sustain a bias that’s been proven to do harm to society as a whole?

I’m sure I’m not doing a perfect job. I’ll miss my own biases as I make corrections. But with just a few small changes researchers will be able to find people they might not have found in the past. Even more, people viewing these photographs won’t have social conventions keeping them from really seeing all of the individuals in the pictures.