If you’re a big fan of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s hit musical Hamilton (based on the life of Alexander Hamilton), you may remember the song that Aaron Burr sings about his daughter, “Dear Theodosia.” But what you may not know is that Theodosia Burr’s story comes to a head (that joke will make sense in a minute) in North Carolina.

Theodosia Burr was primarily raised by her father and received the kind of education that was typically reserved for the men of her time. She had a strong relationship with her father and admired him greatly, according to her letters. Among the country’s early framers, Aaron Burr was one of the few early defenders of women’s rights (7:18) (due partially to the influence of Theodosia Prevost, Theodosia Burr’s mother).

Aaron Burr’s dedication to Theodosia’s education helped her become one of the most distinguished women in early American society—and one of the most sought-after. She was apparently pursued by the artist John Vanderlyn and the writer Washington Irving. Vanderlyn allegedly painted Theodosia’s eye as a “memento of his love” (10:32) and wore it on his lapel. The most appealing suitor, though, was Joseph Alston, who would go on to become governor of South Carolina. They were married in February 1801 in Albany, New York (11:34). In 1802, Theodosia gave birth to a son, Aaron Burr Alston (15:09).

In 1807, Aaron Burr was tried and acquitted of treason, leaving his political reputation in a sorry state. To escape the negative attention, he went into self-imposed exile in England, where he stayed for four years. The separation was apparently hard on Theodosia, who didn’t see her father during that period. Then, in 1812, her son died of malaria at the age of 10 (19:50), leaving her even weaker and and more depressed.

When Aaron Burr finally returned to New York in June of 1812, Theodosia was desperate to reunite. However, her poor health made her family worry about travel on land, and the ongoing war meant that most ships had been seized by the Navy to fight the British (20:14). Finally, in the fall of 1812, Alston secured a small pilot boat, The Patriot, to take Theodosia up the East Coast from Charleston to New York. As Oscar Stradley explains (5:26), the boat was designed to sail close to the shore and arrive in New York in 5 to 6 days. Theodosia and the crew of The Patriot left Charleston on December 30, 1812.

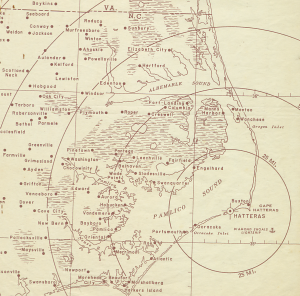

A quick sidebar is necessary here to explain what happened next—and it involves our old friend Hamilton. As many North Carolinians know, the Outer Banks has a long history as a treacherous area for sailors, especially on dark nights, when the coastline is hard to see (not to mention the threat of pirates, which we’ll get to in a minute). Alexander Hamilton, who was personally familiar with the “graveyard of the Atlantic,” used his influence within the Washington and Adams administrations to get funding for lighthouses (1:50). He was successful in securing funding for one famous gal in 1794: Cape Hatteras.

Although Cape Hatteras provided some light for ships around Hatteras and Ocracoke by the time it was lit in 1803, by 1812, there still wasn’t good lighting around Nags Head, which is to the north (close to Kitty Hawk and Kill Devil Hills). This set up the perfect opportunity for land pirates in the area.

Although Cape Hatteras provided some light for ships around Hatteras and Ocracoke by the time it was lit in 1803, by 1812, there still wasn’t good lighting around Nags Head, which is to the north (close to Kitty Hawk and Kill Devil Hills). This set up the perfect opportunity for land pirates in the area.

On dark nights (which are especially common in the fall and winter in the Outer Banks), pirates would lure ships aground with a sneaky trick: they would tie a lantern to the neck of the ponies commonly found on the islands and lead them up and down the hills (6:48). From the perspective of boats on the water, this looked a lot like the light on another ship bobbing nearby (a “nag” is a name for an old horse).

Although the details of what happened to Theodosia and the crew of The Patriot are still a bit of a mystery, accounts of pirates that surfaced in the 1830s led people to believe that the boat was taken in by this trick at Nags Head. Stradley notes that the crew may have been trying to determine their location when they accidentally ran ashore and fell victim to pirate murder (8:20).

The reason that we think Theodosia made it to the Outer Banks comes down to one enticingly-vague clue: a portrait that is probably of Theodosia. In Stradley’s telling, Theodosia escaped the initial pirate attack with the portrait of herself, which she intended to give to her father when she arrived in New York. The pirates may have left her on the beach, he posits, because of superstition surrounding people with mental illness, or people “whose minds had been taken by God” (10:59).

The portrait was rediscovered by Dr. William Poole, a physician from Elizabeth City who made a house call to a small fishing cabin on Nags Head in 1869 (12:06). Apparently, the owner of the cabin gave the portrait as payment for medical treatment. The portrait has a strong resemblance to Theodosia’s earlier portraits, and when it was discovered, some of her surviving family members confirmed the likeness (39:10).

Stradley tells this part of the story as if Dr. Poole was called to treat Theodosia herself (who, in 1869, would have been in her late eighties). Before Dr. Poole could take the portrait, however, Theodosia allegedly grabbed it off the wall, ran out of the cabin, and disappeared into the night (she was a sprightly eighty-six) (12:55). The portrait was later found washed up on the beach, and Theodosia was assumed to have drowned.

Another version, explained by Marjorie Berry, historian for Pasquotank County, says that Dr. Poole was called into the cabin of Mrs. Polly Mann, a fisherman’s widow (27:30). The portrait stood out in the otherwise plain cabin, so Dr. Poole asked where it came from. Mrs. Mann explained that her old beau, Joseph Tillet, had been one of the ship’s wreckers, and that he had gifted her two black dresses and the portrait, which he had taken as his share of the loot. (In this version, the wreckers had found the ship already empty when they arrived.)

In contrast, the report that Aaron Burr received, according to Berry, was that Theodosia was drowned by a storm. Since British ships were waiting off the coast of North Carolina (they were, after all, in a war), one admiral sent Burr a message describing a rough storm that hit the Outer Banks on January 2, 1812—around the time that The Patriot would have been there (29:44). The fact that there was a huge storm in the area is a detail missing from all the pirate confessions that came forward, leaving some doubt as to their veracity.

Whatever happened to Theodosia Burr, the story of her life and disappearance has been told and retold in Northeastern North Carolina many times; a copy of her portrait is on display in the Our Story Exhibit at the Museum of the Albemarle. You can hear the Oscar Stradley’s full version of the story here (courtesy of Mitchell Community College) and Marjorie Berry’s version in the recording of “History and Highballs: Theodosia Burr” from the North Carolina Museum of History.