Analyzing Political Cartoons

Document Presets

To download, choose the "Save as PDF" option when asked to choose a printer.

Primary Source Set

Analyzing Political Cartoons

One of the ways that newspaper publishers express their views is through political cartoons. This editorial form became popular over the 20th century for the way it can quickly and forcefully deliver a viewpoint to its audience—particularly in decades when not all adults could read. This primary source set uses examples of political cartoons from school and community newspapers to show how the form has evolved over the last 100 years.

Proceed with caution and care through these materials as the content may be disturbing or difficult to review. Please read DigitalNC’s Harmful Content statement for further guidance.

Time Period

20th Century

Grade Level

9 – 12

Selected Sources

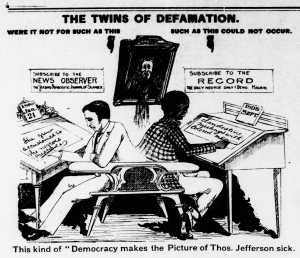

The Caucasian (Clinton, N.C.), October 20, 1898

Clinton, N.C. (Sampson County), 1898

Despite its name, The Caucasian was a prominent newspaper for the Farmers’ Alliance and Populist party, which tended to oppose the white-supremacist Democratic party of the late 1800s. It was owned by Marion Butler, a farmer and teacher from Sampson county who went on to become a U.S. Senator in 1895.

In this cartoon, the two newspapers being referenced are the white-owned Raleigh News & Observer and the Black-owned Daily Record, based in Wilmington, N.C. These two newspapers were at the center of the 1898 Wilmington Coup, when the owners of the Raleigh News & Observer used political cartoons to stoke fear among white voters about the Black prosperity in Wilmington and overthrow the elected government. On November 10, 1898, a white mob seized control of the government, burned down the offices of the Daily Record, and killed at least 60 Black citizens.

This cartoon was published just a few weeks before, on October 20, 1898. The articles that the two people in the cartoon are writing were famous at the time; the first one, published in the News Observer, condemned a relationship between a white woman and a Black man. The response article, written by the editor of the Daily Record, Alex Manly, argued that white women entered relationships with Black men willingly—a claim that enraged white conservatives. The blurb below the cartoon (omitted here due to racist language) reprints excerpts from both articles.

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The Morning Post (Raleigh, N.C.), Jan. 14, 1900

Raleigh, N.C. (Wake County), 1900

From the mid-1800s until the ratification of the 19th Amendment in 1920, many women rallied behind the cause of women’s suffrage, or the ability to vote. Though women’s suffrage was most popularly associated with white leaders like Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, Black women, like Ida B. Wells and Mary Church Terrell, were also central to the fight.

This cartoon was published in 1900, when Susan B. Anthony stepped down as the movement’s central leader. Her successor, Carrie Chapman Catt, began directing energy toward a constitutional amendment rather than voting rights in all states. While this strategy created public discussion of women’s rights, activists struggled for many years to convince people that women should participate in civic life.

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

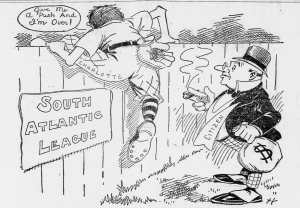

The Charlotte News (Charlotte, N.C.), December 7, 1906

Charlotte, N.C. (Mecklenburg County), 1906

While some political cartoons take a stance on national issues, in the early 1900s, several cartoonists also focused on local issues that readers of their towns or counties would recognize. Andrew Hutchinson, who used the name “Hutch” to sign his work, was a local artist who drew cartoons for The Charlotte News.

The subject of this cartoon appears to be the Charlotte Hornets, Charlotte’s minor league baseball team from 1902-1972 (not to be confused with the basketball team of today). Baseball teams are assigned to play in regional leagues based on players’ talent, and in 1906, the South Atlantic League (nicknamed the “Sally League”) was apparently one to reach for.

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

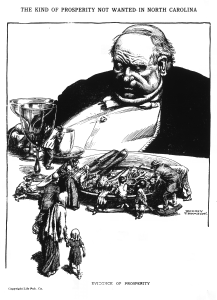

The State Journal (Raleigh, N.C), March 7, 1913

Raleigh, N.C. (Wake County), 1913

This cartoon was published as the cover of The State Journal on March 7, 1913. The paper was founded not long before, in February 1913, with the purpose of “help[ing] North Carolinians to know each other better.” Many of the articles are opinion pieces written by R. F. Beasley and Alex J. Feild.

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

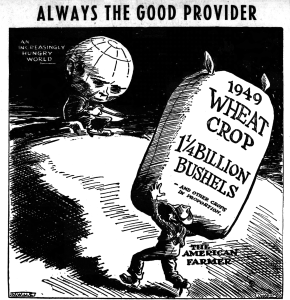

The Elkin Tribune (Elkin, N.C.), July 28, 1949

Elkin, N.C. (Surry County, Wilkes County), 1949

Many North Carolinians in the 1940s were farmers—and many of them faced similar problems to farmers today. After World War II (1939-1945), for example, farmers had better technology for producing more crops, but that didn’t guarantee them economic security. One solution used by the federal government was the creation of Farm Bills, which helped address income support, agricultural education programs, and more. This cartoon was published in the rural community of Elkin between the Agricultural Acts (Farm Bills) of 1948 and 1949.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Elkin Public Library, Northwestern Regional Library

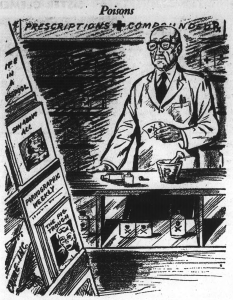

North Carolina Catholic (Nazareth, N.C.), May 22, 1953

Nazareth, N.C. (now Raleigh, N.C.) (Wake County), 1953

The North Carolina Catholic comes from Nazareth, a Catholic community in Raleigh. This paper circulated for Catholics all over the state since, in 1953, all of North Carolina was within the Diocese of Raleigh (a diocese is the district of one bishop). The “Poisons” cartoon, published on May 22, shows a pharmacist making medications at his work bench in a drug store—which looks different from the drug stores of today. The article criticizing the cartoon was published two weeks later.

While the cartoon and the response are most critically focused on the magazines in the store (which read “Life in a Cesspool,” “Sin Above All,” “Pornographic Weekly,” etc.), these titles allude to a larger social issue. In the early 1950s, there was some experimentation with hormonal birth control (the FDA approved the first contraceptive pill in 1960), which would allow people greater freedom to have sex, especially outside of marriage. The Catholic Church was one of the strongest opponents of contraceptives, which may be part of the reason that this cartoon targets pharmacists specifically.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Catholic Diocese of Raleigh

North Carolina Catholic (Nazareth, N.C.), June 5, 1953

Nazareth, N.C. (now Raleigh, N.C.) (Wake County), 1953

The North Carolina Catholic comes from Nazareth, a Catholic community in Raleigh. This paper circulated for Catholics all over the state since, in 1953, all of North Carolina was within the Diocese of Raleigh (a diocese is the district of one bishop). The “Poisons” cartoon, published on May 22, shows a pharmacist making medications at his work bench in a drug store—which looks different from the drug stores of today. The article criticizing the cartoon was published two weeks later.

While the cartoon and the response are most critically focused on the magazines in the store (which read “Life in a Cesspool,” “Sin Above All,” “Pornographic Weekly,” etc.), these titles allude to a larger social issue. In the early 1950s, there was some experimentation with hormonal birth control (the FDA approved the first contraceptive pill in 1960), which would allow people greater freedom to have sex, especially outside of marriage. The Catholic Church was one of the strongest opponents of contraceptives, which may be part of the reason that this cartoon targets pharmacists specifically.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Catholic Diocese of Raleigh

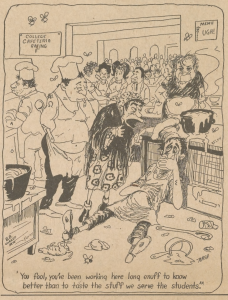

The Campus Echo (Durham, N.C.), April 30, 1962

Durham, N.C. (Durham County), 1962

Another place where hyper-local political cartoons can be effective is on school campuses, where students likely have their own set of interests and issues. This comic is from North Carolina Central University, then called North Carolina College at Durham, which is a historically Black university. This cartoon was drawn by Willie Nash, a student at NCC who went on to become a prominent artist.

Contributed to DigitalNC by North Carolina Central University

Watauga Democrat (Boone, N.C.), Jan. 7, 1965

Boone, N.C. (Watauga County), 1965

This cartoon was created by Henry McCarn, a political cartoonist born in Belmont, N.C. In 1963, he started a syndicate that sent weekly cartoons to small newspapers across North Carolina and other states. Part of his business strategy was to create cartoons that were politically neutral to avoid offending newspaper readers.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Watauga County Public Library

The Front Page (Raleigh, N.C.), Feb. 28, 1980

Raleigh, N.C. (Wake County), 1980

The Front Page was a newspaper published in Raleigh for gay and lesbian readers (it later merged with Q-Notes, based in Charlotte). Many of the articles focus on issues relevant to gay readers, and the advertisements show businesses that were LGBTQ-friendly. This cartoon was created by Robert Kirby, a cartoonist featured in gay publications around the country.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Duke University, University of North Carolina at Charlotte

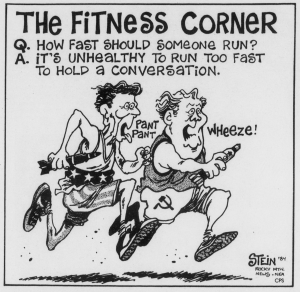

The Guilfordian (Greensboro, N.C.), September 12, 1984

Greensboro, N.C. (Guilford County), 1984

This cartoon was published in 1984, which was during a period of tension between the United States and the Soviet Union (a federation of countries including modern-day Russia, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, Belarus, and others). This tension was part of the end of the Cold War, an extended conflict between these two world powers and their allies to gain global influence. A major part of the Cold War was the arms race, where both sides endeavored to create and stockpile more powerful nuclear weapons than their rival.

Near the end of the Cold War, there was public pressure on world leaders to engage in diplomacy and eliminate the threat of nuclear warfare. Readers of The Guilfordian, the student newspaper at Guilford College in Greensboro, N.C., would have recognized the two people in this cartoon as U.S President Ronald Reagan (left) and Konstantin Chernenko, the leader of the Soviet Union (right). This cartoon was created by Ed Stein, a famous cartoonist for The Rocky Mountain News in Denver, Colorado.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Guilford College

The Winston-Salem Chronicle (Winston-Salem, N.C.), January 1, 1998

Winston-Salem, N.C. (Forsyth County), 1998

This cartoon comes from The Winston-Salem Chronicle, a Black-owned newspaper in Winston-Salem, N.C. It references the government’s gradual involvement with the HIV and AIDS epidemic between 1981 and the late 1990s, a time when millions of people were infected with the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which can lead to acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS).

While HIV and AIDS activism during this time is most commonly associated with white gay men in groups like ACT UP New York, in 1998, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that Black Americans accounted for 49% of AIDS-related deaths—nearly ten times the rate of white Americans. Additionally, the vast majority of people infected with HIV worldwide (70%) lived in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Forsyth County Public Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

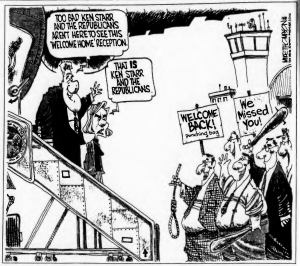

The News-Journal (Raeford, N.C.), July 22, 1998

Raeford, N.C. (Hoke County), 1998

Caricatures of public figures became more prominent in political cartoons in the second half of the 20th century. This example is from July 1998, the beginning of an investigation into claims of sexual assault by President Bill Clinton. In this cartoon, Clinton is shown stepping off an airplane with his wife, Hillary Clinton. Ken Starr, the person they are talking about, was the lawyer (known as independent counsel) who was investigating President Clinton.

A few months later, in September 1998, Congress charged President Clinton with four articles of impeachment—crimes such as lying under oath and obstructing justice—to try to remove him from office. While this cartoon was published before the impeachment process began, it captures some of the political tension between Clinton (a Democrat) and Republicans in Congress. This cartoon was drawn for a national audience by Mike Thompson.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Hoke County Public Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

The Seahawk (Wilmington, N.C.), April 24, 2003

Wilmington, N.C. (New Hanover County), 2003

Another example of a national cartoon finding a place in a local paper is this one from the University of North Carolina Wilmington’s (UNC-W) student newspaper. In 2003, amid heightened fear of Islamic extremism after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush conducted a U.S. invasion of Iraq. He asserted that the attack was motivated by the desire to remove Saddam Hussein from power and based on fear that Hussein had stockpiled “weapons of mass destruction.” Vice President Dick Cheney also warned against Iraqi control of oil.

By the end of April, U.S. forces had seized power and were beginning work on a transitional government in Iraq. In this cartoon, President Bush (right) is assembling a puppet with his Secretary of State, Colin Powell (left). This example is one of the many critical cartoons made about the Bush administration since no weapons of mass destruction were discovered in Iraq, though U.S. troops stayed in the country until 2011.

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Wilmington

The Daily Tar Heel (Chapel Hill, N.C.), September 15, 2003

Chapel Hill, N.C. (Orange County), 2003

This cartoon is an example of a student journalist applying a national issue to a local context. In the early 2000s, a company called Napster allowed people to share music files with each other for free—though they quickly ran into copyright infringement problems. This cartoon depicts two neighboring dorm rooms; on the left are two students smoking, and on the right is a student being arrested by the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) as she listens to what is likely illegally downloaded music.

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Background

Many newspapers in the 20th and 21st centuries include editorial sections designed to make arguments or give opinions about topics in the news. One way for newspaper editors to present an opinion is through political cartoons. While these cartoons can be funny and entertaining, their primary purpose is to quickly make an argument about a political or social issue. Political cartoons can be found in all kinds of newspapers published in many different countries and can be used to address any issue that the audience of the newspaper recognizes. Many times, the artists address polarizing issues with cartoons or push the boundaries in an effort to evoke a reaction from readers.

Political cartoons often use some of the same rhetorical devices as written articles, including irony, symbolism, and analogy. Cartoons also have their own rhetorical devices, such as exaggerating characteristics of a particular person and labeling things to tell you what they represent. Sometimes, the meaning of the cartoon is made clear through a short title or caption. Additionally, understanding political cartoons usually requires knowing their contexts. Many of them contain representations of famous people or references to historical events. It may also help to know the intended audience of the newspaper.

Note: Some political cartoons depict stereotypes that may be uncomfortable to see. While the examples in this set avoid offensive imagery as much as possible, other pages of these newspapers may include it.

Discussion Questions

What do you see in this cartoon? Who are the characters? What are they doing?

What rhetorical devices is this cartoonist using? What elements are exaggerated or humorous?

What is the argument the cartoon is making? How do you know?

What does this cartoon tell you about this newspaper? Who is their primary audience? What viewpoints do they want to convey?

Do you find the cartoon’s point persuasive? Why or why not?

These materials were compiled by Sophie Hollis. Updated March 2025.

https://www.digitalnc.org/primary-source-sets/political-cartoons/

This document was prepared for print on September 18, 2025.