Jim Crow South: Life in North Carolina Post Civil War-1930’s

Document Presets

To download, choose the "Save as PDF" option when asked to choose a printer.

Primary Source Set

Jim Crow South: Life in North Carolina Post Civil War-1930’s

Following the long history of enslavement and the resulting Civil War, states within the U.S. adopted racist and segregationist policies that became known as Jim Crow laws. The years that these laws were in place (starting after the Civil War through 1968) came to be known as the Jim Crow era. This assortment of newspapers, photographs, and other types of documentation describes the lived experiences of people in North Carolina during Jim Crow post Civil War to the 1930’s.

Proceed with caution and care through these materials as the content may be disturbing or difficult to review. Specifically, there are mentions and descriptions of racist and white supremacist violence and murders, oppression based on race, racist and white supremacist language, and offensive former race labels. Please read DigitalNC’s Harmful Content statement for further guidance.

Time Period

1865-1930's

Selected Sources

The South II

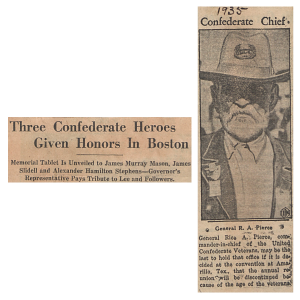

Granville County, North Carolina (Granville County), 1935

This scrapbook contains a collection of newspaper articles, photographs and annotations showing varying Southern perspectives post-Civil War. There are articles about the Confederacy and the ending of the war, many from a pro-Confederacy stance, including the featured articles on honoring confederate soldiers, including R.A. Pierce. In viewing the entire sources, there are also articles from the 1950’s and 1960’s about integration efforts, showing both the vitriol experienced by many Black students entering white schools and some examples of relatively easier integration efforts.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Granville County Public Library

Tis Sixty Years Since: A Story of the University of North Carolina in the 1800s

University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (Person County, Orange County), 1970

The author, James Lee Love, attended the University of North Carolina and wrote this book about the history of the university post-Civil War to 1945, when the book was published. Here, Love describes the general atmosphere on the campus during this time, which was prior to the admittance of any Black students. However, this is not the beginning of Black history at UNC Chapel Hill, enslaved people were sold for services to the university and students during slavery, David Swain (former governor and university president) alone had 40 people enslaved for the university. Love begins the book detailing the Reconstruction era after the Civil War and its impact on UNC and the college “servants” who were most likely the same formerly enslaved people that continued their roles at the university post-enslavement. He then goes on to describe UNC students in 1886 threatening local residents of the historically Black neighborhood near campus.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Person County Public Library

The weekly standard. (Raleigh, N.C.) [7/27/1870]

Raleigh, NC (Wake County, Alamance County, Guilford County, Caswell County, Cumberland County), 1870

The Weekly Standard, whose editor at the time was Wiliam Alexander Smith, was based in Raleigh, NC. This edition included opinion pieces on the rise of the Klu Klux Klan (KKK) and the ties to North Carolina’s Democratic party and its politicians. While still politically motivated to increase support for the Republican party, the articles in the newspaper reflected the conditions in the state and the connections between Democratic politicians and the rise of the KKK. On page two, the paper had reprinted a statement by the current Governor and the Standard’s former editor, William W. Holden, on the long list of racial violence perpetrated by the KKK in North Carolina in detail, as well as the governor’s call for military intervention to end the KKK’s activity in the state. Eventually, the persons detained for these crimes were released, and the Democratic party gained momentum in North Carolina, effectively instituting white supremacy and Jim Crow across the state.

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

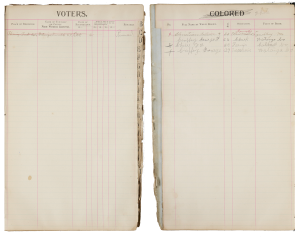

Blowing Rock's First Voter Registration Poll

Blowing Rock, NC (Watauga County, Caldwell County), 1970

This shows the vote registration for Blowing Rock, NC, for different elections from 1890-1900. Throughout the documented registration, voters were recorded according to race. Some lists designating the race have been marked out and re-written to reflect the race of the registrants listed.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Blowing Rock Historical Society

The Wilmington herald. (Wilmington, N.C.) [10/18/1894]

Wilmington, NC (New Hanover County), 1894

“We applaud the right and condemn the wrong; justice to all and malice to none,” was the tagline of The Wilmington Herald, a Black newspaper in Wilmington, NC. This issue appeals to Black voters to reject populist Democrat candidates and instead vote for the Republican ticket. It shares their observations that the Republican officials do not always follow through with their campaign promises, but that it is a better alternative to a Democrat-ran government “filled with ex-klukluxes.” It also includes an ad from James Fowler soliciting funds to purchase property in the West for an independently Black community, free from the oppression faced in the rest of the country.

Contributed to DigitalNC by State Archives of North Carolina

'To the Executive Committee' The Daily Record. (Wilmington, N.C.) [8/26/1898]

Wilmington, NC (New Hanover County), 1898

The Daily Record was a Black newspaper in Wilmington, NC, that published until the Wilmington Massacre (also known as the Wilmington Coup) in November 1898. The paper had been under scrutiny throughout the state for an article published on August 18, 1898, stating that the recent lynchings against Black men for allegedly sexually assaulting white women were unfounded murders. In this issue, the paper addresses the renunciation it has received from the Republican party and the attention of Democrat-leaning papers. Unfortunately, there are now only seven issues known to remain of the Daily Record.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Cape Fear Museum

'What Is There to Fear?' The Daily Record. (Wilmington, N.C.) [10/20/1898]

Wilmington, NC (New Hanover County), 1898

The Daily Record was a historically Black newspaper in Wilmington, NC, that published until the Wilmington Massacre (also known as the Wilmington Coup) in November 1898. In this issue, the editor included commentary on the upcoming election. The article addressed the rising tension and inflamed rhetoric from anti-Black politicians, newspapers, and paramilitary terrorist groups (i.e. the Red Shirts) that did not want to see democratically elected Black politicians in power. The paper stated that “They [the Red Shirts] have talked freely of forcing their way to election, and to those who are not familiar with the people of this city they get the impression that there is danger of bloodshed and riot… If Wilmington was the half civilized town some try to make it appear, there might indeed be danger, but such is not the case. We have here a class of people who delight in law and order, who will not lend aid to any act of violence and they are the ones wh[o] very largely control the masses.” This was published less than a month before the election of Black public officials for the town of Wilmington and the resulting massacre of at least 14 confirmed deaths (estimated total deaths range from 60 to over 300 people), along with the burning of the Daily Record’s office building and many homes.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Cape Fear Museum

The semi-weekly messenger. (Wilmington, N.C.) [11/25/1898]

Wilmington, NC (New Hanover County), 1898

The Semi-Weekly Messenger was a part of The Wilmington Messenger publication. This paper features an article on the front page addressing the Wilmington Massacre (also known as the Wilmington Coup). It states that the Republican papers are “liars” and had misconstrued the facts for their own political agenda. The article states that the Black population of Wilmington had actually started the fight and that the two days after the election had been a government of “disorder and danger.” The paper states that the actions of the massacre were justified and because of this, there was “no further trouble between the two races here unless caused by the [Black population] themselves. All is quiet and peace reigns supreme.”

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, State Archives of North Carolina

Greensboro telegram. (Greensboro, N.C.) [7/7/1900]

Greensboro, NC (Guilford County), 1900

The Greensboro Telegram was a newspaper based in Greensboro, NC, and in 1900 it had a strong Democrat, white supremacy leaning to its editing. This edition features an article titled “Plea for White Supremacy: Strong Speech by a Brave Man,” which features a public speech given by Dan Hugh McLean, who was a former Confederate soldier. The paper applauded his statements that Black voters were a “menace to the safety of the white man” and his warning that a failure to vote would lead to racial equality that would spur mass Black migration to the state of North Carolina.

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

'Negroes Must Be Given Equal Accommodations With Whites On Rwy’s' The Charlotte news. (Charlotte, N.C.) [7/8/1907]

Charlotte, NC (Mecklenburg County), 1907

The Associated Press made an appearance in this edition of The Charlotte News, through a reprinted article on a recent court case. It addressed the discrimination in interstate transportation by railroad companies which provided substandard accommodations to people of color. The courts maintained the ‘separate but equal’ Jim Crow laws governing the country, stating that there had to be separate accommodations based on race, but that the accommodations should effectively offer the same amenities.

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, State Archives of North Carolina

'Judge Pell Fears Abolition of “Jim Crow” Cars Under Government Control' The Raleigh independent. (Raleigh, N.C.) [12/21/1918]

Raleigh, NC (Wake County), 1918

The Raleigh Independent was an influential Black newspaper in the Raleigh area, reporting on local and national issues affecting the Black community. In this issue, the paper reports on North Carolina Judge Pell imploring senators to oppose the nationalization of railroads to “prevent the calamity” of ending Jim Crow and integrating public transportation. This issue also includes reports on Black military members, who were in their own segregated military units, and the upcoming Emancipation Day celebration.

Contributed to DigitalNC by State Archives of North Carolina

Mrs. Dusenbury and Mrs. Cooper Classes, Hill Street School [1919]

Hill Street School, Asheville, NC (Buncombe County), 1919

Pictured is a classroom at the Hill Street School shared by two teachers and their classes, displaying the overcrowding. Students are seated at desks and standing in their segregated school in Asheville, NC. This school was located in a historically Black neighborhood in Asheville. This can be compared to white schools which were better funded and therefore tended to have more resources and less issues with overcrowding.

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Asheville

The Raleigh Independent. (Raleigh, N.C.) [9/4/1920]

Raleigh, NC (Wake County), 1920

The Raleigh Independent was an influential Black newspaper in the Raleigh area, reporting on local and national issues affecting the Black community. Here, the paper reprints articles from the Raleigh Times on the recent lynching in Graham, NC, and from the Associated Negroe Press on women’s suffrage and the potential future for Black women who can now legally vote. The Independent reported on the passing of the 19th amendment and that with the new reality of Black women entering the voting population “[w]hite supremacy is again shaken to the very cellar floor.”

Contributed to DigitalNC by State Archives of North Carolina

Chinqua-Penn Plantation Gate House

Reidsville, NC (Rockingham County), 1923

The Chinqua-Penn Plantation was a home constructed circa 1923 and owned by Thomas Jefferson Penn of Reidsville, NC. Shown here are people in front of the plantation gatehouse being constructed, which was located in Rockingham County, NC. In the photo, there are two groups physically separated in the photo by race, with all the white people on the left, and all the Black or non-white people on the right. Penn was also the author of ‘My Black Mammy: A True Story of the Southland.’

Contributed to DigitalNC by Rockingham Community College

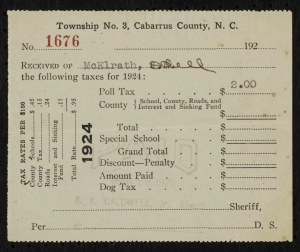

Poll Tax Receipt of Odell McElrath, 1924

Cabarrus County, NC (Cabarrus County), 1924

In 1924, Odell McElrath is shown to have paid his $2 poll tax. His receipt was a part of an exhibit at the Levine Museum of the New South. This is after the amendment to the state’s constitution to eliminate poll taxes as a requirement to vote in 1919. This accompanies his other poll tax receipt from 1922.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Levine Museum of the New South

Background

The Advent of Slavery in the United States

Slavery had become a global institution with the rise of colonialism and the ideology of distinct races; a chosen hierarchy accompanied this construct, now known as white supremacy, and was used to justify the violence enacted through colonization. As the now named Americas were colonized, enslaved people from Africa began to be brought to the colonies during the early 1600’s, and the practice of slavery grew exponentially from this point.

Slavery was a strongly held American institution until the idea of abolition began to gain more widespread support in the early and mid-1800’s. Many people had been strongly advocating against the violent practice of slavery and undermining its power over enslaved people since its inception, and the 1800’s saw a culmination of these efforts. Regardless of the motivations, whether moral or economic, the reality of abolition became clear and a Civil War (1861-1865) resulted between the industrial Northern states within the Union and the Southern states, which held most of the enslaved population and, consequently, those that most directly profited from the continued practice of slavery.

Post-Civil War Reconstruction

After the Emancipation Proclamation (1863) issued by president Lincoln declaring the end of slavery and then the Union’s victory in the Civil War (1865), the Reconstruction period began in the South to rebuild and restructure the post-war region, circa 1865-1877. The 13th amendment was ratified into the Constitution and officially prohibited the practice of slavery within the United States. However, the legacy of slavery and racism persisted; its influence could be found in the language of the 13th amendment that abolished slavery (except for slavery in the form of being incarcerated), in the newly created laws that continued white supremacist ideology, and in the everyday actions and anti-Black beliefs held by individuals throughout the country.

“Jim Crow”

The term ‘Jim Crow’ came from the phrase coined by a popular song used in minstrel shows, which were performances centered on mocking African Americans. This is also where the act of Black-face gained popularity. The racist phrase ‘Jim Crow’ became the name given to the era of repression and segregation in the United States marked by racist and segregationist laws. It prohibited non-white people from certain areas or from engaging in certain activities (e.g. drinking from separate water fountains or only being allowed to sit in designated sections of public venues). More discreet laws were implemented discriminatorily, like requiring a poll tax or written test in order to vote. This began primarily after the Reconstruction period in response to the increased participation of Black people in the community and politics, especially with the success of Black politicians in being elected in Southern states.

These laws were in place throughout the country, not only the South, although the South’s history with slavery and resentment from its abolition among politicians and former slaveholders created a hostile environment in the region. Many people began to identify certain areas as “Sundown Towns” because they knew them to be unsafe for any Black person to visit after dark. Some towns even had signs that proclaimed the entire area “for whites only,” much like those posted by businesses or on public restrooms throughout the country.

People experienced oppression both structurally through these racist laws and personally from individual people. Strongly held racist ideologies gave rise to white supremacist organizations, like the Klu Klux Klan, and spontaneous mobs that resulted in terrorizing Black people and the practice of lynchings. The reality of life throughout the South was marred by violence and oppression, and these occurrences became mostly Southern violence.

Resistance to Oppression

In response, communities began to organize and resist structural and communal oppression. Many Black communities were founded during this time due to segregation, and their exclusion from public life saw the creation of many Black-owned businesses. In North Carolina, there were multiple Black-run newspapers that reported both on the issues their community was facing and that celebrated their joys and accomplishments. For example, you could find on a front page both an update on possible desegregation of interstate transportation, as well as congratulations for the recently graduated local high school students.

While the passing of the Civil Rights Act in 1965 and the Fair Housing Act of 1968 saw the legal end of explicit Jim Crow laws, some would argue that Jim Crow persists in the racist policies and practices still ingrained in many institutions, like under-funding historically Black communities. By exploring the documented history and the lived experiences of people during this time in North Carolina, we can understand its impacts and lasting effects on people and our communities.

Discussion Questions

Wilmington Massacre

- Compare the article written by The Daily Record prior to the massacre and then the article by the Semi-Weekly after the massacre. With no other information, what would you conclude to have happened during the Wilmington Massacre?*

- Now read this article on the background of the events. Did your perspective of the events change? What information was brought to light that was not included, was altered, or was denied by the semi-weekly?*

- What political or personal agendas/perspectives were at play in the publishing of the daily record and the semi-weekly? How might people have determined the truth of the events in 1898?**

- When analyzing mass media (e.g newspapers, tv news outlets, etc.), how can people determine the underlying agendas that influence how information is presented?**

- In a world supposedly filled with “fake news,” how do people determine what is “true” news? Should news be true to be considered information? If so, is untrue news not information? Why or why not?**

- How does morality and ethics relate to truth and what does it mean for certain ideologies (e.g. integration or racial justice) to become societal norms/truths?**

Greensboro Telegram (1900) and Goodbye Carolina (1964)

- Read the article “Plea for White Supremacy: Strong Speech by a Brave Man” from the Greensboro Telegram and then watch the “Goodbye Carolina” video from 1964. How do these pieces of media stand in opposition to each other?*

- Were the fears of mass Black migration to North Carolina if racial equality through voter’s rights were achieved as described in the article in the Greensboro Telegram a founded fear? Why or why not?**

- Review this 1962 article “Elections and Mass Media” by Stanley Kelley Jr. What role did mass media play in campaigning during the 1900 election cycle in North Carolina? How does it play a role in our elections today?*

- Read the article “Plea for White Supremacy: Strong Speech by a Brave Man” from the Greensboro Telegram and then watch the “Goodbye Carolina” video from 1964. How do these pieces of media stand in opposition to each other?*

Reality of Voting in NC

- Review this article on NCPedia’s website about the history of the poll tax in NC. What would you say the policy for access to voting would be before and after the amendment in 1919?*

- Now review these poll tax receipts (one and two), this voter registration list from Blowing Rock, NC, and this 1952 article regarding access to voting in NC. What do these documents tell you about the realities of voting and access to voting in North Carolina during Jim Crow? Do you think that access to voting was consistent across the state?**

- Based on historic methods of undermining access to voting, how do you think that legacy impacts us today? Can you find any evidence that confirms or refutes your suppositions?**

After reviewing the examples of newspaper articles from historically Black-owned newspapers and historically white-owned newspapers in North Carolina, what is the significance of having Black-run newspapers during this time?**

After viewing the classroom of Mrs. Dunesbury’s and Mrs. Cooper’s classroom, compare this to Jamestown, NC white school classroom. What differences do you notice? What does this tell you about the funding and support for these different schools?*

- Does this point to any issues with the “separate but equal” policy instituted through Plessy v. Ferguson? Why or why not?**

What can you conclude about the reality of the Jim Crow era in North Carolina based on these sources?**

* Questions that check for comprehension

** Questions that involve a “deeper dive” in conceptual and historical analysis

These materials were compiled by cal lane. Updated May 2025.

https://www.digitalnc.org/primary-source-sets/the-jim-crow-south-life-in-north-carolina-post-civil-war-1930s/

This document was prepared for print on September 1, 2025.