Folk Arts and Crafts

Document Presets

To download, choose the "Save as PDF" option when asked to choose a printer.

Primary Source Set

Folk Arts and Crafts

While there is some debate over the terms, folk arts are art items or performances created by untrained, non-academic artisans using traditional or cultural methods of art production. These do not usually have a functional use beyond being an art piece. Folk crafts are similar, though these crafts do serve some functional purpose beyond their aesthetic use. This source set examines a variety of examples of folk arts and folk crafts from North Carolina and the many people who have lived here.

Time Period

1931-1995

Selected Sources

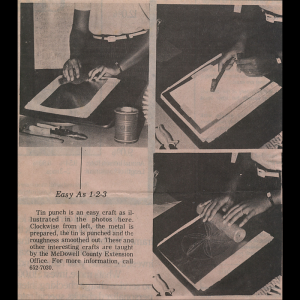

Arts and Crafts in McDowell County Scrapbook 1

McDowell County, NC (McDowell County), 1975

Tin production increased during colonization throughout colonies in what is now called the Americas. English colonizers brought the art of tinsmithing to the now United States and the art of tin punching spread with the craft. In other areas, tin production made the metal significantly cheaper and became incorporated into previous folk art and craft traditions, like in Mexico. Tin punching is done by using thin sheets of tin and punching patterns into the sheet to make art or craft pieces like lantern covers. Artists in McDowell County taught this folk art, an important aspect of the revival of many folk arts and crafts.

Contributed to DigitalNC by McDowell County Public Library

Clement Tombstone

Davie County, NC (Davie County), 1978

Tombstones, or grave stones, became an interesting folk art in North Carolina; stone carvers typically did this ornamentation without training or recognition as an artist. Over time, these artisans developed an intricate and widespread folk art practice. The designs became more elaborate and lengthy epithets were added. Here, Reverend Albert Clement’s granddaughters stand with his tombstone, an example of the growing trend in this folk art with its dove design and long script carved into the stone.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Davie County Public Library

Jubilee Folk Singers Present Black Music in Historical Perspective

Raleigh, NC (Wake County), 1972

An early genre of folk music in the American colonies, the spiritual is part of the foundation of Black folk music, which originated in the American South during slavery. This music is an intertwining of West African musical traditional and European Christian hymns that tell the stories of slavery and oppression, passing on these stories of death, violence, resistance, spirituality, and hope. This folk art has been preserved through the generations and is now performed on stage by groups like the Jubilee Folk Singers. Some have started to call these spirituals African-American or Black spirituals, but others maintain that they should be referred to as they were originally. Dr. Everett McCorvey, researcher and founder of the American Spiritual Ensemble, has this to say about the history and naming of this folk music:

“The term ‘American Negro Spirituals’ speaks to the history, the suffering, the hope and the resolve of a people who were able to sing through their suffering and tell and re-tell their heroic stories of triumph and survival through these songs. It is a story and a history that hopefully will never be forgotten. And while the songs were born out of this very dark period in our American History, these songs are now sung, celebrated, and revered all around the world. While some of the language in the music is updated in order to be sung in a more contemporary style and to remove the barrier of dialect, the melodies, the sentiment and the stories of the spirituals are over 400 years old and need to be sung and remembered. I would encourage teachers and singers to be comfortable with calling the melodies what they are. They are ‘American Negro Spirituals.’ Please feel free to call them ‘Negro Spirituals’ or just ‘Spirituals’ or ‘American Negro Spirituals,’ but the ultimate goal is for these melodies to be celebrated and sung by all.”

Contributed to DigitalNC by Wake County Public Libraries

Folk Dancing

Brasstown, NC (Cherokee County, Clay County), 1970

This photograph was taken at the John C. Campbell Folk School, an example of a folk dance being taught and learned there. A project begun by John C. Campbell and completed by his wife Olive and her friend Marguerite Butler, the school was developed by non-Southerners looking to establish a folk school like those found in Denmark. They decided to build in Appalachia as the fascination with the mountain region and interventions there became more popular. Olive and Marguerite settled on Brasstown after revisiting the area and finding substantial community interest in the possibility of a folk school. This was also during the time when tourism to the area and subsequent sale of handicrafts were on the rise, potentially contributing to the community’s interest in establishing the school. The school has continued to be a hub of learning and practice for a variety of folk arts and crafts; notably, it has helped the local tradition of Brasstown carvers continue to flourish over the years.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Clay County Historical and Arts Council

Over & Under, Around & Through: A Basketry Exhibition

Brasstown, NC (Cherokee County, Clay County), 1993

Basketry, or basket weaving, has been practiced for millennia as a functional folk craft to store or carry items. Basket weaving is the process of using either organic materials (like reeds or plants) or synthetic materials and interlacing them in a specific way to create a container. This can be done through coiling, plaiting, twining, wicker weaving, or ribbed construction. There are many folk traditions with basket weaving, and the full exhibit program describes Black/African American, Indigenous, and Appalachian basketry. The photo shows an example of the Cherokee tribe’s folk tradition of basket weaving.

Contributed to DigitalNC by North Carolina Humanities Council

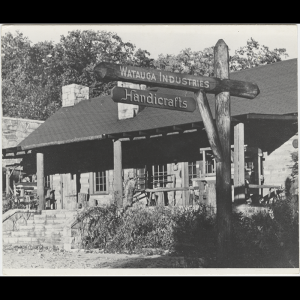

Watauga Industries: Handicrafts

Boone, NC (Watauga County), 1950

During the late 19th century and early 20th century, interest in American folk traditions increased, creating a demand for folk arts and crafts. This demand created the Craft Revival in Appalachia, where people began creating folk art and crafts for sale for those interested in these “by-gone” practices. The combination of this consumer culture and the economic hardships for many in Appalachia saw the rise in these handicrafts shops and expanded sale of folk traditions. The success of these shops were due in part to the increase in tourism to Appalachia over the years.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Watauga County Public Library, Appalachian Regional Library

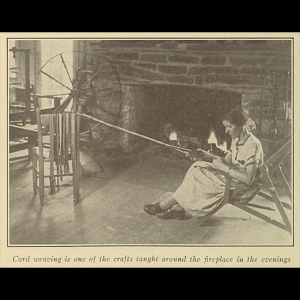

Penland Cord Weaving (Catalogs, 1939-1943)

Penland, NC (Mitchell County), 1943

Cord weaving is a practice used in both basket weaving and seat making for chairs. The cord is used in weaving techniques and was a popular method in mid-century Scandinavian furniture making using Danish cord. This example is from a cord weaving demonstration at Penland School of Craft. The School was founded in 1929 by Lucy Morgan, who returned to Penland after studying weaving at Berea College. She eventually took her economic development project of teaching the local women how to weave into a fully functional folk craft school. Penland continues to teach the practice of a variety of crafts, and has taught many people over the years folk crafts and traditional methods of making. Today, they teach in-person classes, online workshops, and host artisan residencies.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Penland School of Craft

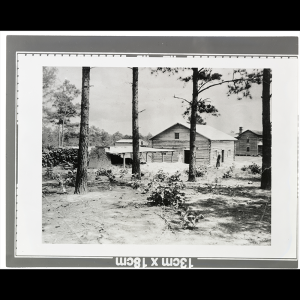

Cole Pottery - Building and kiln

Sanford, NC (Lee County), 1934

The folk craft tradition of pottery in North Carolina predates colonization with indigenous folk ways creating pottery. Later settlers used the knowledge of the area’s rich clay soil to begin their own pottery traditions. One of the prominently known settler families that contributed to the craft was the Cole family. Their history of practicing pottery is traced back to their origins in England and Wales, adopting their techniques once settling in North Carolina. This photo shows the upright kiln and business building for Cole Pottery in Lee County, which was moved from its original location in Randolph County in 1934. The owner and primary potter, Arthur Cole, was known for his spatterware and signature red-orange glaze. That specific colored glaze technique was lost after Arthur Cole’s death in 1974, two years after the State Highway commission ordered Cole to move his kiln and pottery studio in order to use the land for a new highway and interchange. The family has at least ten generations of potters, which continued this folk craft tradition through to the 21st century.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Railroad House Historical Association and Museum

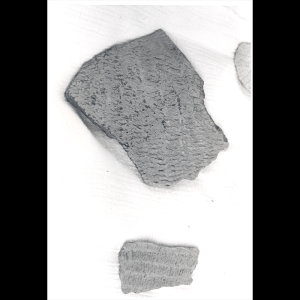

Fragments of American Indian Pottery from Collection of Richard Flint, Edgecombe County, N.C.

Edgecombe County, NC (Edgecombe County), 1976

Native potters, as the original inhabitants and stewards of this land, developed pottery techniques specific to the clay rich soil and natural resources found here. Cherokee potters typically used coil-building methods for their craft tradition. Meanwhile, Catawba potters typically painted their pottery with red-orange and black colors. In the 20th century, the indigenous folk tradition of pottery transitioned towards appealing to the growing tourism in the state and the accompanying market for folk crafts and art. The pottery fragments featured here were part of a collection in Edgecombe County, which would make the creators potentially either from the Skaruhreh/Tuscarora tribe or the Lumbee tribe according to the land tracking available through Native Land Digital for Edgecombe County.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Edgecombe County Memorial Library

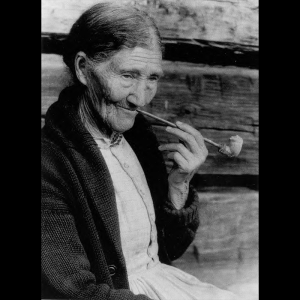

Aunt Sophie Campbell

Haywood County, NC (Haywood County), 1931

Shown with one of her pipes, Sophie Campbell was a folk crafter that produced clay pipes and bowls. She lived in the Smoky Mountains area of Appalachia and has been remembered by both East Tennesseans and Western North Carolinians from Gatlinburg, TN, and Maggie Valley, NC. People recalled that she would sell her wares to passing hikers on their way through the Appalachian Trail. This is reflective of typical folk pottery found in North Carolina, along with pitchers, jugs, and churns. As a part of this craft, an interesting folk tradition that made its way into North Carolina was face pottery, specifically face jugs, that originated with potters who were enslaved in South Carolina.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Haywood County Public Library

Arts in Durham, Jazz in the Park and Taproots

Durham, NC (Durham County), 1979

Growing out of African musical traditions, spirituals, and rural African American/Black work songs, jazz has been seen as a folk art that was brought into the musical mainstream in the early 1900’s. Folk musicians incorporated their own community’s musical traditions to make distinct practices of jazz within the overall folk tradition of this musical genre. Jazz musician and composer Yusuf Salim can be seen in this filmed performance during Jazz in the Park. Salim became a prominent figure in the jazz culture of Durham

Contributed to DigitalNC by Durham County Library

Arts in Durham, Arthur Hall Dance Company

Durham, NC (Durham County), 1980

Afro-American dance is a term encompassing a wide range of dance styles and traditions. It is used to group together the folk dances originating in African American/Black communities. Many of these dances were later taken from these communities and their roots in local dance halls and community gathering spaces to the mainstream dance world. Examples of the different folk traditions or trends in Afro-American dance are the twist, break dancing, disco, and the Harlem shake. In this film produced by the Durham Arts Council and the Durham Technical Institute, Arthur Hall, a dancer and choreographer originally from Memphis, TN, spent time in Durham in 1980 teaching Afro-American dance. In this interview, he speaks on his experience and highlights the classes he was teaching in the Durham community.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Durham County Library

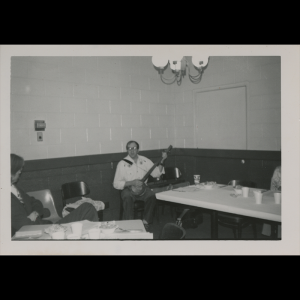

Folk Musician Clark Jones

Sanford, NC (Lee County), 1976

Clark Jones, who grew up in Charlotte, NC, traveled around North Carolina absorbing folk music found in North Carolina communities. He had learned to play many stringed instruments, like the guitar, banjo, and dulcimer, and later recorded some of the over 600 folk songs he had learned during his life. North Carolina, like many other places, have folk songs centering on religious themes, labor, and daily life. Each community has its own traditions and influence, but interesting cultural influences found in some of the state’s regions are from Irish, Scottish, and Caribbean traditions.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Central Carolina Community College

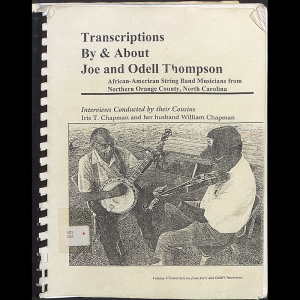

Transcripts By & About Joe and Odell Thompson: African-American String Band Musicians from Northern Orange County, North Carolina

Carrboro, NC (Orange County, Alamance County), 1995

Joe Thompson and Odell Thompson, cousins from outside of Mebane, NC, were folk musicians that played African-American string band music, or what they referred to as “old-time music.” This style is highly influential in many veins of now-American folk music as it enmeshed African rhythms and the banjo with European fiddle and dance music. As with all music, each folk musician takes the traditional and adds their own personality to it, advancing the lineage of folk music practitioners. Joe played the fiddle, the same instrument his father played, and Odell similarly played the same instrument as his father, the banjo. While they played much of their lives, they were encouraged to share their music more broadly after being visited by a UNC Chapel Hill graduate student studying folklore. They eventually went on to be awarded a North Carolina Folk Heritage Award in 1991, recognizing the lasting mark the cousins left on North Carolina’s folk music history.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Alamance County Public Libraries

Knitting and crochet class

Sanford, NC (Lee County), 1980

Some of the earliest examples of knitting can be found in Egypt and the practice of knitting spread across the globe, communities implementing their own versions and creating their folk art of knitting. The origins of crochet can be found in various cultures, distinct examples from China as well as what we now call the Middle East and South America. Notably, cultures across the world from each other developed traditions of folk crafts with fiber material that were practical and artistic. These traditions have also become influenced by each other, particularly in a US context; many of us have probably seen or owned a pair of mittens with Lithuanian folk art influence. Like the Central Carolina Technical College class featured here, The John C. Campbell Folk School in Brasstown, NC, teaches knitting and crochet classes to continue the tradition of this folk craft. They also highlight an employee and crafter Kate Clayton Donaldson who was known for her appliqued crochet blankets that can now be seen on display in the school’s History Center, Southern Highland Craft Guild, and the American Folk Art Museum. Another North Carolinian recognized for her contributions to the craft is Nancy Lavada Miller Fisher from Transylvania County, who was known for her crocheted blankets and clothing.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Central Carolina Community College

Background

When learning about the history and traditions of folk arts and crafts, we must define the terms ‘folk art’ and ‘folk craft’.

Folk art is a term used to describe art that is created by untrained artists that use traditional and/or cultural methods for creating art instead of following an academic or professional methodology. These folk arts usually do not have any functional purpose beyond being a piece of art.

Folk crafts are also made by untrained, non-academic people who use traditional and/or cultural means of producing items, though folk crafts do have a functional purpose beyond their artisanal aesthetic. The two are extremely similar in terms of who makes them and the culturally grounded creation process, but it is the functionality that distinguishes them in formal definitions.

Folk arts and crafts have existed for as long as people have been creating, and these traditions continue through to today. Artists and craftspeople create paintings, pottery, wood carvings, sculptures, and even tombstones They reflect the folklife (or the ways of living) of a given community, and showcase both similarities and differences between communities. These communities are often defined geographically, but also have roots in religious, racial, ethnic, and/or cultural identities. Some communities overlap and meld in identity and tradition, from Appalachian to African-American/Black folk arts and crafts.

Folklife and traditions like folk arts and crafts help people to form and define their identities and better understand how they relate to others. By examining folk arts and crafts, this source set aims to show the variety of folklife and traditions found in the state and asks us to examine our own relationship to folklife and each other.

Discussion Questions

Assumptions About Folklife

- Before starting with this primary source set, what were your assumptions or knowledge of folklife and folk arts and crafts?**

- What did these folk arts and crafts reveal about life in North Carolina for the communities featured in the primary sources?**

- What evidence did these primary sources provide to either reinforce or challenge your previous understanding of folklife, arts, and crafts?**

- How might this impact the way you engage with folklife and practices in the future?**

Folk Traditions across Communities

- When considering folk music, what connections are evident between the folk musicians Clark Jones, Yusuf Salim, Odell Thompson, and Joe Thompson?*

- What other examples from the primary source sets can relate to these folk music traditions?*

- What might be different about their experience with and traditions of folk music?**

- Examples of pottery traditions were shown from unnamed indigenous people held in Edgecombe County, the Cole family in Lee County, and Aunt Sophie Campbell in Haywood County.

- What points of connection can be made between the different traditions?*

- How do these traditions differ?*

- How might the different communities these people belonged to impact how their pottery is treated and viewed today?**

- What North Carolina communities represented in the primary sources were you already familiar with in regards to their folk art and craft traditions?*

- What communities’ traditions had you not encountered before?*

- What may have contributed to your previous familiarity or lack thereof?**

- What communities’ traditions had you not encountered before?*

- In what ways have folk arts and crafts changed over time?**

- What are the factors that contributed to these changes?**

- When considering folk music, what connections are evident between the folk musicians Clark Jones, Yusuf Salim, Odell Thompson, and Joe Thompson?*

Folk Art and Craft Influence

- What influences were noticeable in the primary sources?*

- What influences on North Carolina folk art and craft traditions can be found through further research or reviewing the context for each primary source?**

- What does this reveal about folk life in general?**

- What does this reveal about the impact of globalization and colonization on folklife and folk traditions?**

- What influences were present that you would not have expected?**

- What influences were absent that you may have expected to be present?**

- What influences were noticeable in the primary sources?*

For Teachers

- "Selling Tradition" Chapter 5 'I Start as Early as I Can and Work as Hard as I Can: Mountain Craft Producers and Their Work' by Jane S. Becker

- "Selling Tradition" Chapter 6 - 'Labor or Leisure?: Industrial Homework and the Redefinition of Craftsmanship' by Jane S. Becker

- "Selling Tradition" Chapter 7 'Selling Tradition' by Jane S. Becker

https://www.digitalnc.org/primary-source-sets/folk-arts-and-crafts/

This document was prepared for print on September 1, 2025.