Viewing search results for "University of North Carolina at Greensboro"

View All Posts

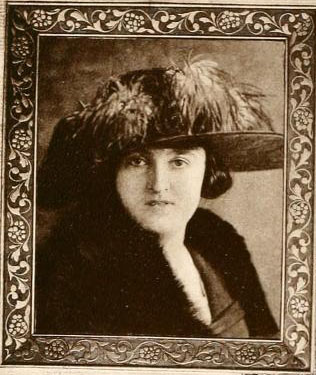

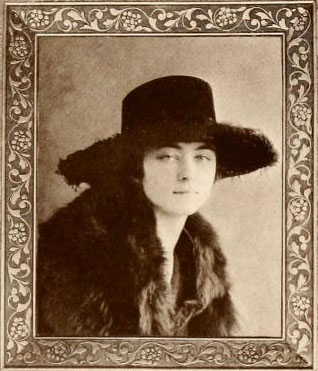

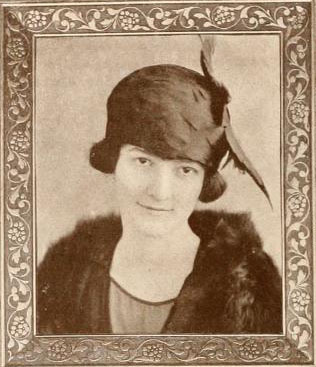

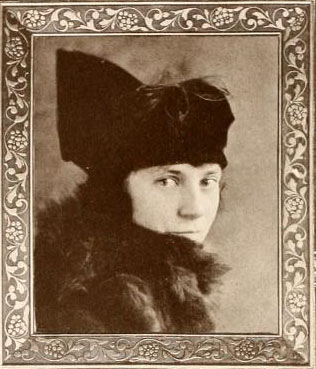

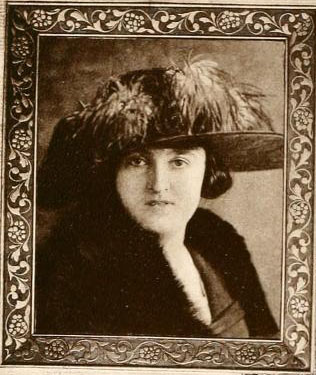

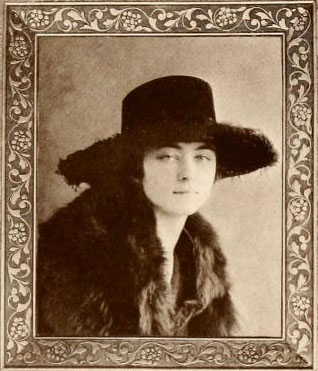

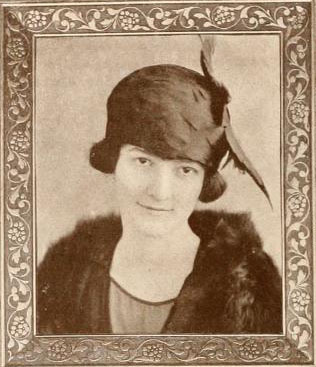

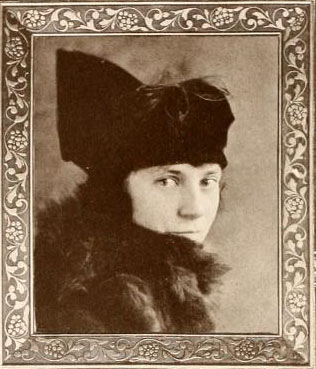

In the many thousands of yearbook photos now available through the North Carolina College and University Yearbooks collection, you’d be hard-pressed to find a more elegant group of students than the Greensboro College class of 1919. Yearbook photos were clearly an occasion that called for putting on your finest and striking a dramatic pose. Most of the women are pictured in fantastic hats and many of them are wearing furs. There are a few examples here, and many more in the full volume.

Thanks to our partner, the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, a batch of yearbooks from high schools in Guilford and Wilkes counties are now available on our website. This batch includes yearbooks from Ronda High School, Pleasant Garden High School, Millers Creek High School, McLeansville High School, Sumner High School, Alamance High School, Southeast High School, Walter Hines Page High School, and Summerfield Public School. The issues in this batch span the years 1948-1964.

The cover of the 1960 issue of the Alamance High School yearbook.

For more information about the University of North Carolina at Greensboro, please visit their website.

In today’s blog post I offer a break from the current election year with a trip back to the 1968 presidential election. Looking at the political landscape of 1968 is like looking at an earlier but familiar view of the same neighborhood we’re in now. It’s issues resonate today: striving for social and racial equality, debates over America’s place on the world stage. The late 60s were boiling with the turmoil of the Civil Rights Era and the Vietnam War. 1968 alone saw the assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in early April and presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy in June.

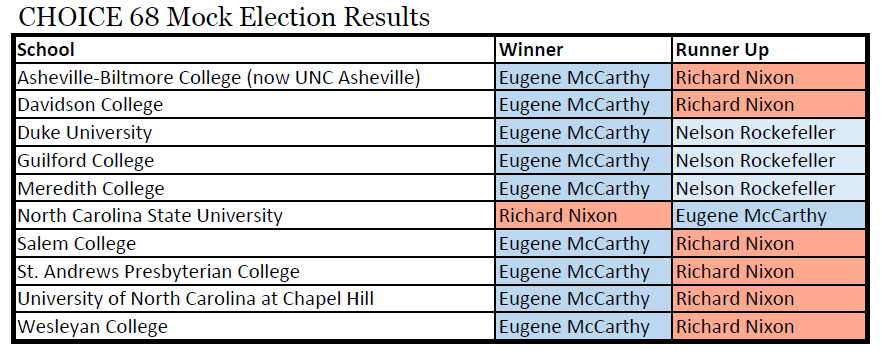

In April 1968, Time magazine held a mock presidential primary at colleges and universities to take the temperature of young Americans during that election year. Dubbed “CHOICE 68,” the event was covered in many of the student newspapers that can be found on DigitalNC, and I wanted to see what this nation-wide event looked like here in North Carolina.

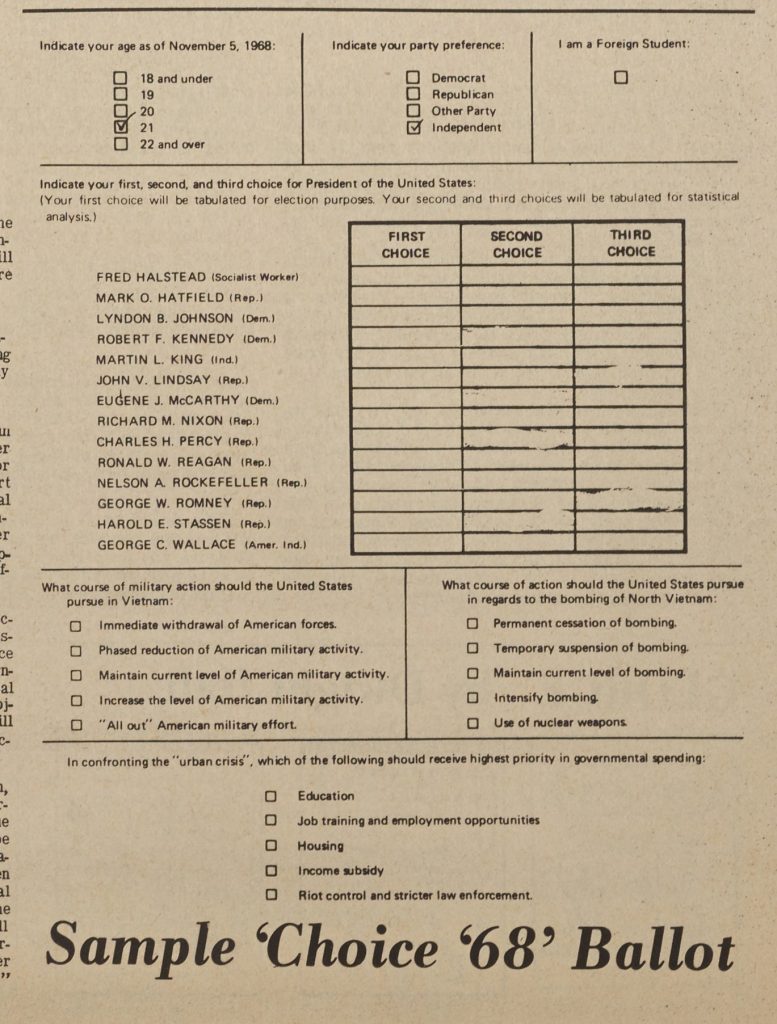

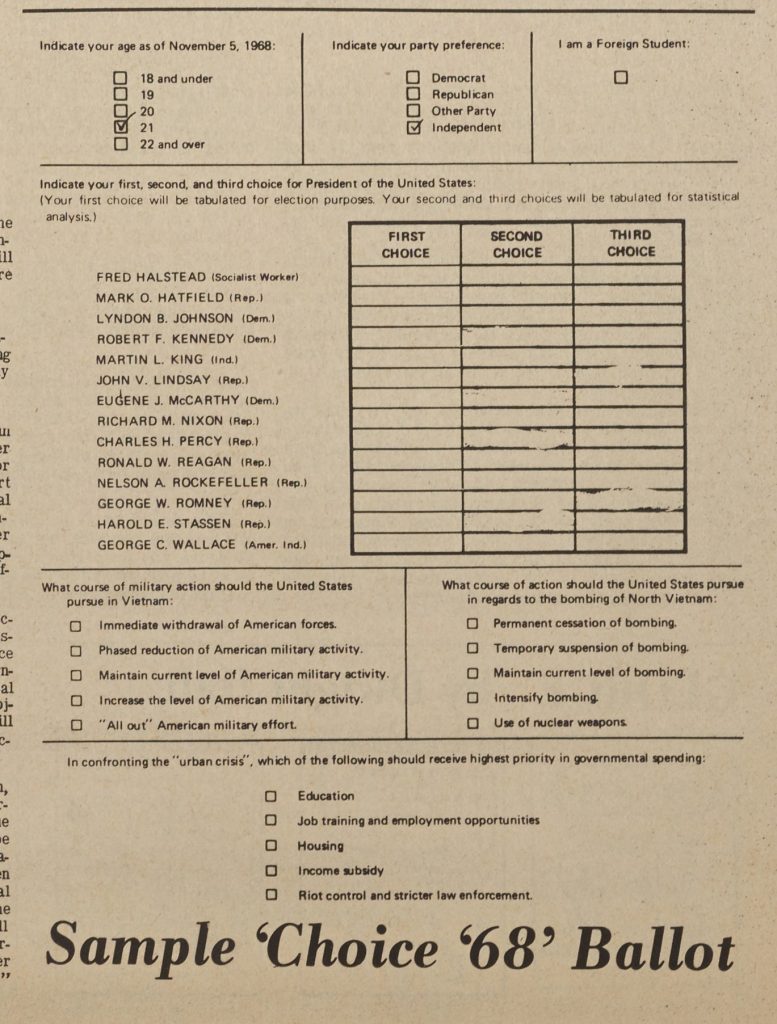

Sample Choice 68 Ballot, printed in Asheville-Biltmore College (now UNCA) newspaper The Ridgerunner, March 1, 1968.

Every American college and university was asked to participate in CHOICE 68. The event was governed by a group of eleven students representing a variety of campuses around the country. Campus groups were in charge of publicizing the event with their peers, under the direction of a campus coordinator. Each ballot (an early draft is shown at right) asked students to rank their top three choices for president and also asked for them to weigh in on Vietnam and the “urban crisis,” the latter of which referred to pervasive concern over poverty, crime, and general unrest in high population urban environments. Write-in candidates were also allowed. Votes from all campuses were tabulated by a UNIVAC computer in Washington, D.C. and the results were supposedly announced on television, with each school’s individual totals being returned during the first week of May.

Before the vote, student newspapers urged their readers to rally against apathy, to prove that young voters could impact the national arena. One Brevard College editorial called on moderates to vote, expressing frustration that liberal and conservative activists had been “hoarding the headlines.” An accompanying editorial talked about the conservatives still being committed to rooting out Communism, revealing lingering echoes of McCarthyism from the late 50s. It predicted a 1968 election win for then Governor of California, Ronald Reagan.

Campuses with active student government associations and/or political groups tended to have more events and publicity associated with CHOICE 68. North Carolina Wesleyan College’s student body listened to speeches in support of Senator Eugene McCarthy (D), former Vice President Richard Nixon (R), and current Vice President Hubert Humphrey (D), three of the most prominent contenders in early 1968. Voting booths, borrowed from the City of Rocky Mount, housed students punching out chads of computer cards to cast their votes.

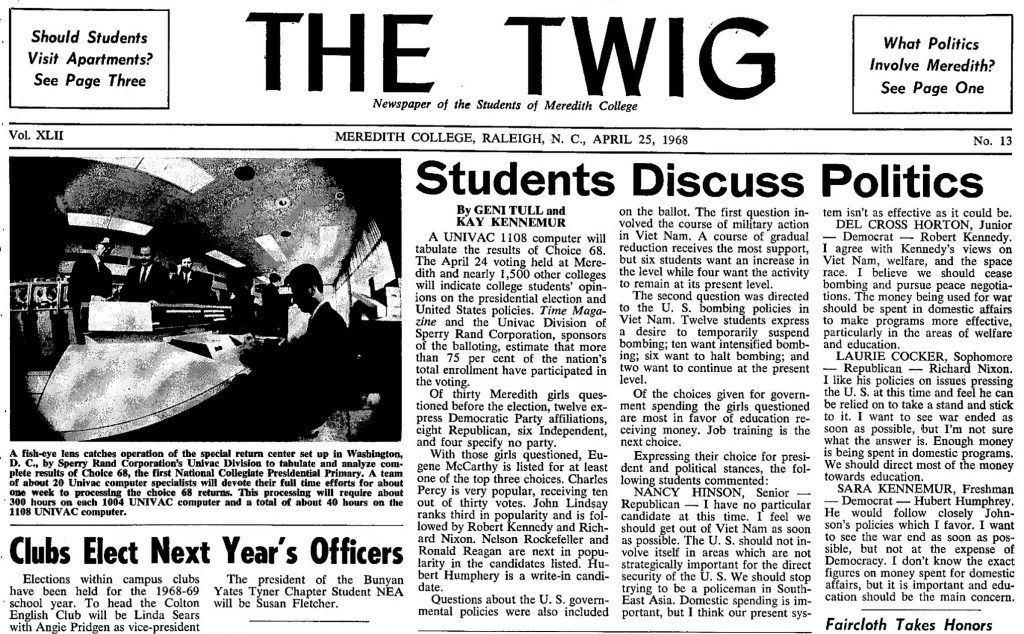

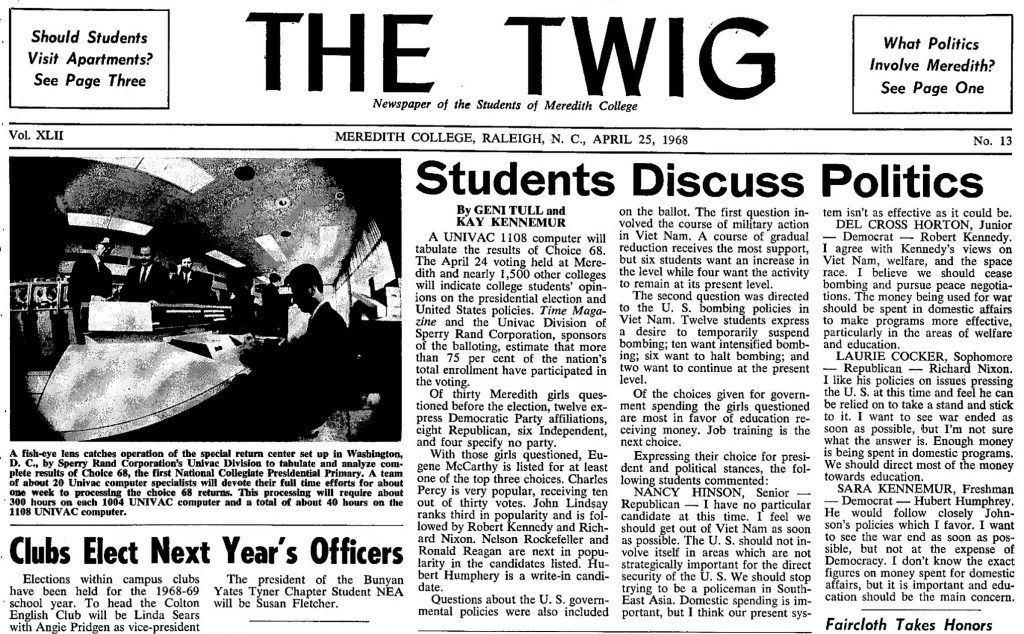

Headline from the April 25, 1968 issue of The Twig, Meredith College.

Some schools had hundreds of participants, with 500 Elon students voting in the mock election. Others had fewer; thirty students were questioned at Meredith College. The Twig quoted opinions from four of those 30 (two Republicans and two Democrats) in the issue seen at right.

Salem College appears to have been one of the most enthusiastic participants, with articles about CHOICE 68 found in issues spanning January through May and a voter turnout of 73% of the eligible student body. The February 23 issue of The Salemite talked about how President Lyndon Johnson endorsed the national mock election despite the fact that “student dissent over the past year ha[d] been directed primarily against White House policies.” The April 12 issue asserted that “massive student participation in CHOICE 68 can and will affect the course of American politics in 1968.”

Almost all articles about the vote mentioned the UNIVAC computation of results, which was seen as heralding a new era in which computers could make generating results faster and more secure. The Meredith College Twig published a photo of the computer tabulating results in its April 25 issue (shown above). Dr. Hammer of UNIVAC posited a time when “a huge data bank may contain ‘voice prints’ of eligible voters” to authenticate those phoning in their votes (“A Letter from the Publisher,” Time, May 10, 1968, page 21).

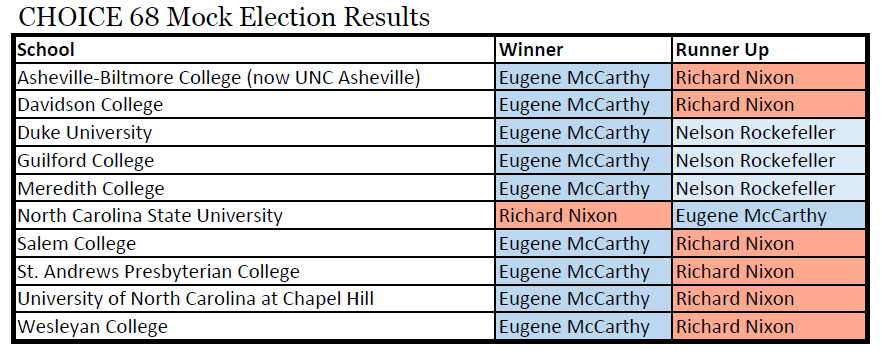

Of the North Carolina schools* whose CHOICE 68 results I could locate, McCarthy came out on top for all except North Carolina State University, where Nixon prevailed and McCarthy came in second. Nixon was the second choice for 7 schools, and Nelson Rockefeller (R) carried second choice at the remaining 3.

The national CHOICE 68 vote also saw McCarthy in the lead with 286,000 out of 1.7 million votes from 1,450 campuses. Robert Kennedy (D) and Nixon followed behind McCarthy. Students voted to reduce the United States military presence in Vietnam, and saw education as the biggest key to solving the “urban crisis.”

Though he won the CHOICE 68 vote and continued to be bolstered by student support through the primaries, McCarthy was beaten by Humphrey to gain the official Democratic nomination. The November election was won by Nixon, however the CHOICE 68 voters’ preference for a Democratic candidate was somewhat predictive: Humphrey prevailed with voters under 30 in the general election.

As far as I can tell, no nationwide poll quite like CHOICE 68 has been held since, though speculation over how college-aged Americans will vote certainly hasn’t changed. If you’re interested in other historical election news and opinion as reported by student newspapers, visit the North Carolina Newspapers collection.

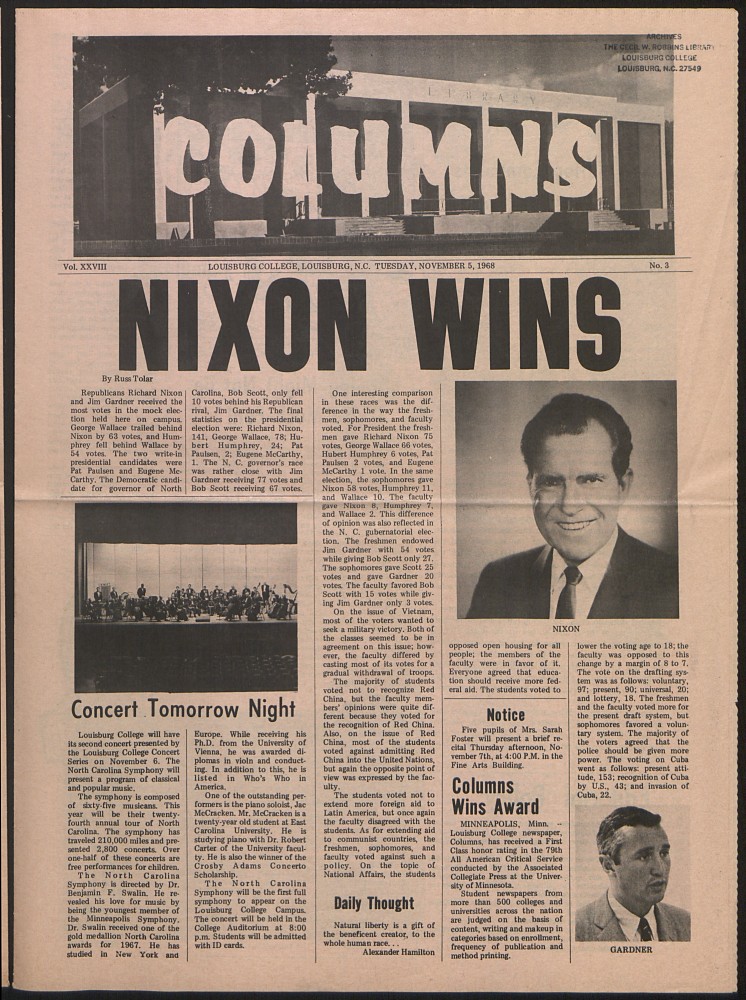

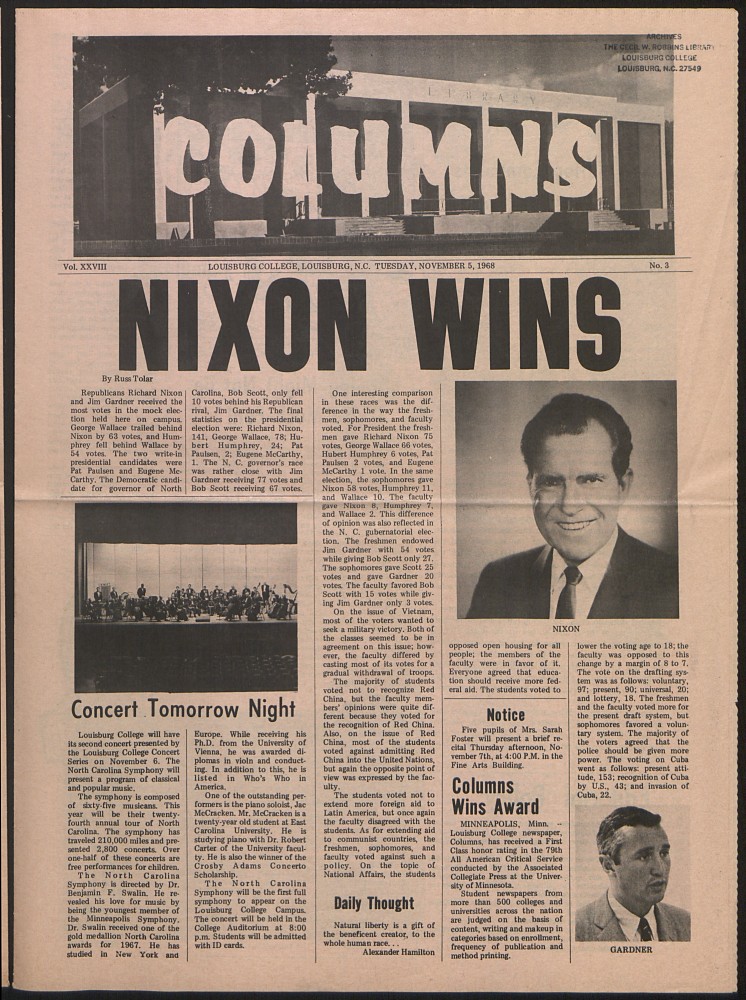

November 5, 1968 issue of the Louisburg College Columns student newspaper. Students picked Nixon in a straw poll held close to the general election.

*It appears that the following schools also participated in CHOICE 68 based on mentions in newspapers and yearbooks, but no results were found: Appalachian State University, High Point College, Lees-McRae College, Lenoir-Rhyne College, Queens College, and University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

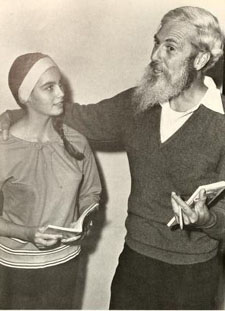

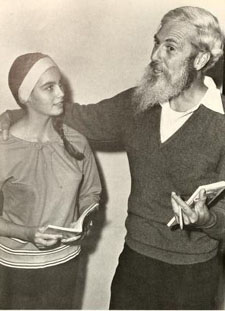

Alabama native Emmylou Harris spent time in North Carolina in the mid 1960s when she was attending the University of North Carolina at Greensboro on a drama scholarship. This photo, from the 1966 edition of Pine Needles, the UNC-Greensboro student yearbook, shows Harris with faculty member Arthur Dixon during rehearsals for The Tempest. Harris played the role of Miranda, daughter of the book-loving magician Prospero. It was apparently (according to her Wikipedia entry) at UNC-Greensboro that Harris began to pursue music seriously, eventually leaving school to try her luck in New York.

Alabama native Emmylou Harris spent time in North Carolina in the mid 1960s when she was attending the University of North Carolina at Greensboro on a drama scholarship. This photo, from the 1966 edition of Pine Needles, the UNC-Greensboro student yearbook, shows Harris with faculty member Arthur Dixon during rehearsals for The Tempest. Harris played the role of Miranda, daughter of the book-loving magician Prospero. It was apparently (according to her Wikipedia entry) at UNC-Greensboro that Harris began to pursue music seriously, eventually leaving school to try her luck in New York.

We’ve recently added more issues of the Africo-American Presbyterian (Wilmington, N.C.) from 1925 to 1938 thanks to our contributors UNC Chapel Hill and Johnson C. Smith University. These editions also offer more regular coverage since we’ve been able to add one from nearly every week in this period.

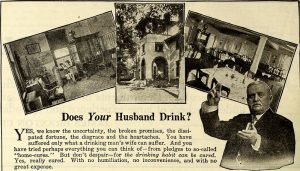

One notable article from the August 20, 1891 issue (from an earlier batch) gives us insight into some of the peculiar medical practices that shaped how we think about addiction today. The headline reads, “Dr. Keeley’s Cure for Drunkenness.”

The treatment proposed here is to inject “bi-chloride of gold” four times a day as an “antidote” to the “disease” of drunkenness. The author of this article compares it to using quinine to treat malaria and mercury to treat syphilis (no longer recommended).

Wilmington wasn’t the only city excited about Keeley’s cure; Leslie E. Keeley actually opened his first clinic in Dwight, Illinois and advertised his cure heavily. By 1892, there were over 100 Keeley clinics throughout the U.S. and Europe reportedly treating 600 people per month.

As chemistry buffs may know, “bi-chloride of gold” would be called dichlorogold today, and it is not used to treat drunkenness or alcohol poisoning. The name seems to have been a bit of a misleader anyway, since Keeley’s real recipe was a mystery. This led the medical community to be a bit more skeptical of Keeley, and his medical license was revoked in 1881 (though it was reinstated a decade later due to procedural issues).

Despite the unreliability of Keeley’s particular recipe, he was one of the first doctors to popularize the idea that addiction is a bodily disease rather than a personal failing.

“The weak will, vice, moral weakness, insanity, criminality, irreligion, and all are results of, and not causes of, inebriety,” Keeley wrote.

And aside from the injections, Keeley’s approach to treating addiction was unlike most methods of the time. According to the article in the Africo-American Presbyterian, patients received the injection “in their own rooms at prescribed hours,” suggesting that they received personal treatment. Some have suggested that a placebo may have also accounted for the success of the treatment; Keeley boasted of 60,000 “graduates” of his program by 1892, indicating its widespread popularity.

Whatever the reasons for his success, Keeley seems to have enjoyed popularity among the Christian publications of North Carolina.

An advertisement for the Keeley Institute in Greensboro, N.C. (1910)

You can see all the issues of the Africo-American Presbyterian here. You can also visit the partner pages of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Johnson C. Smith University for more materials. Visit the Johnson C. Smith University website for more information about the school.

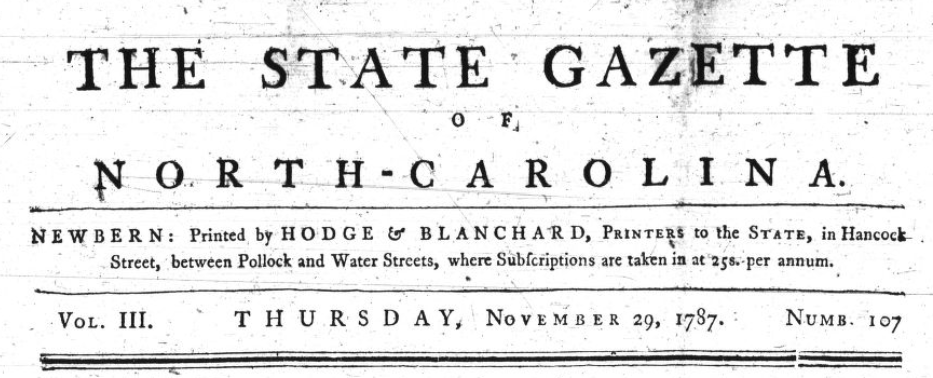

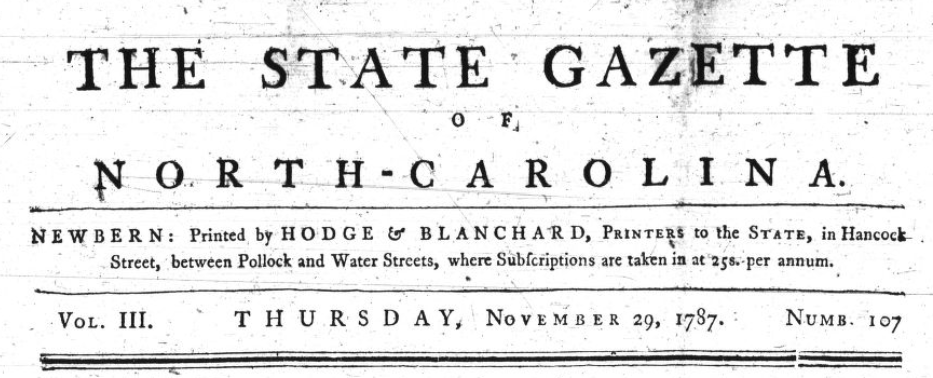

This week we have another 24 titles up on DigitalNC, including one of the state’s oldest papers: The State Gazette of North-Carolina!

The State Gazette was founded by Abraham Hodge and Andrew Blanchard in 1785. Hodge, born 1755 in the colony of New York, worked as a patriot printer during the American Revolution and even operated George Washington’s traveling press at Valley Forge in 1778. While stationed there, he printed official orders, commissions, and recruitment posters for the Continental Army. Seeking a warmer climate after the war, Hodge relocated to Halifax, N.C., where he would go on to own printing presses in Edenton, Halifax, Fayetteville, and New Bern. In addition to newspapers, he was named printer of the North Carolina General Assembly and printed the state’s laws in 1786. He was also one of the first people to contribute to the library of The University of North Carolina.

March 5, 1795 issue of The State Gazette of North-Carolina. Less than a month after The University of North Carolina opened its doors to students.

Over the next year, we’ll be adding millions of newspaper images to DigitalNC. These images were originally digitized a number of years ago in a partnership with Newspapers.com. That project focused on scanning microfilmed papers published before 1923 held by the North Carolina Collection in Wilson Special Collections Library. While you can currently search all of those pre-1923 issues on Newspapers.com, over the next year we will also make them available in our newspaper database as well. This will allow you to search that content alongside the 2 million pages already on our site – all completely open access and free to use.

This week’s additions include:

- The Daily Bulletin (Charlotte, N.C.) – 1862-1863

- Goldsboro Messenger (Goldsboro, N.C.) – 1880-1887

- The Greensborough Patriot (Greensboro, N.C.) – 1851-1856

- The Patriot and Flag (Greensboro, N.C.) – 1857-1858

- The Greensborough Patriot (Greensboro, N.C.) – 1858-1868

- The Patriot and Times (Greensboro, N.C.) – 1868

- The Little Ad (Greensboro, N.C.) – 1860

- The North Carolina Citizen (Asheville, N.C.) – 1878-1880

- The State Gazette of North-Carolina (New Bern, N.C.) – 1787-1796

- The Chatham Record (Pittsboro, N.C.) – 1912-1914

- Eastern Courier (Hertford, N.C.) – 1897-1898

- Economist and Falcon (Elizabeth City, N.C.) – 1891-1893

- Economist (Elizabeth City, N.C.) – 1900-1902

- The Standard (Concord, N.C.) – 1896-1899

- The Daily Standard (Concord, N.C.) – 1892

- The Concord Times (Concord, N.C.) – 1910-1912

- The Evening Tribune (Concord, N.C.) – 1906-1907

- The Concord Daily Tribune (Concord, N.C.) – 1912-1923

- The Davie Record (Mocksville, N.C.) – 1919-1920

- The Anglo-Saxon (Rockingham, N.C.) – 1899-1901

- Fayetteville Observer (Fayetteville, N.C.) – 1896

- The Reporter and Post (Danbury, N.C.) – 1882-1884

- The Danbury Reporter-Post (Danbury, N.C.) – 1884-1891

- The Danbury Reporter (Danbury, N.C.) – 1894-1917

If you want to see all of the newspapers we have available on DigitalNC, you can find them here. Thanks to UNC-Chapel Hill Libraries for permission to and support for adding all of this content as well as the content to come. We also thank the North Caroliniana Society for providing funding to support staff working on this project.

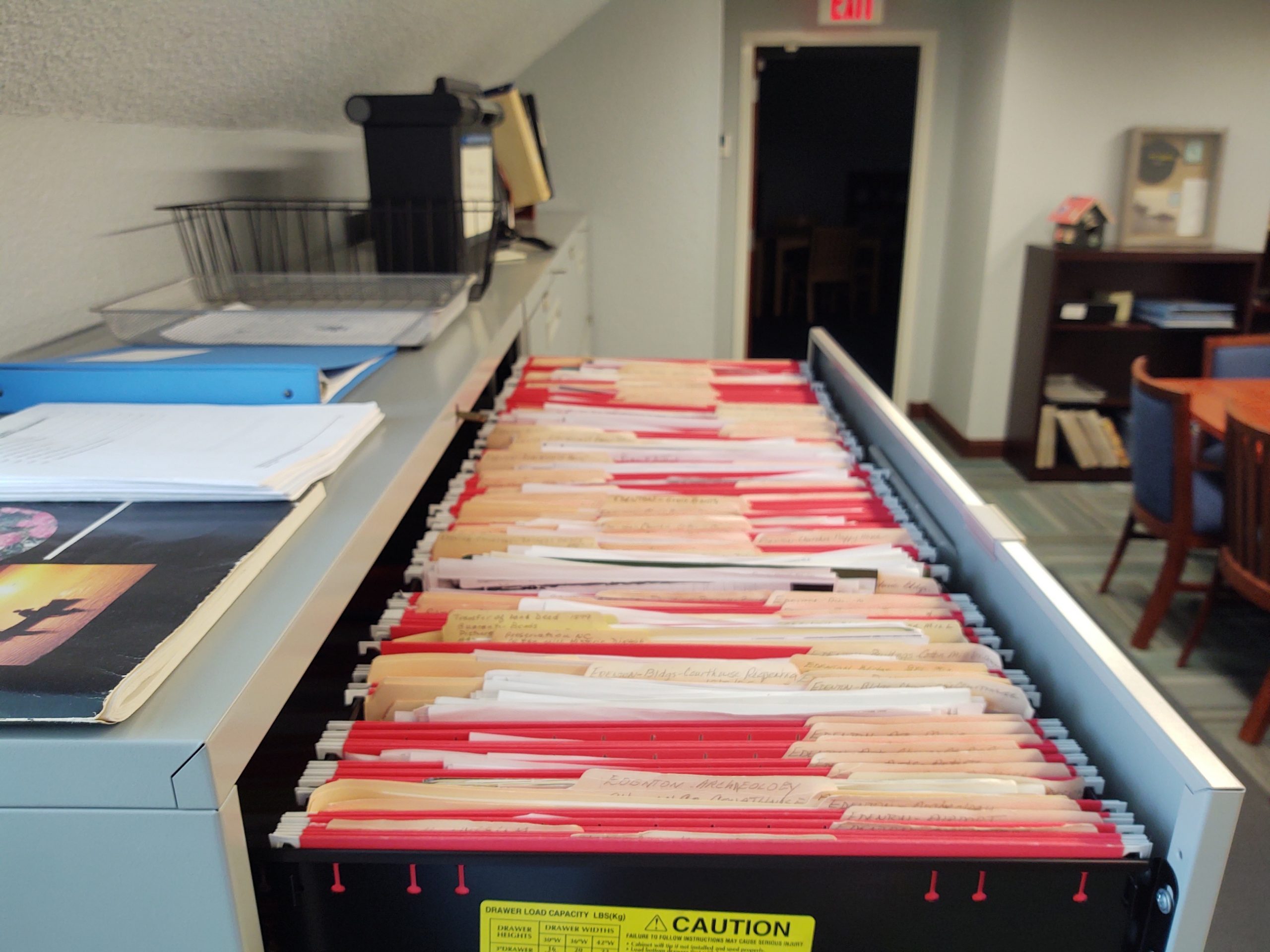

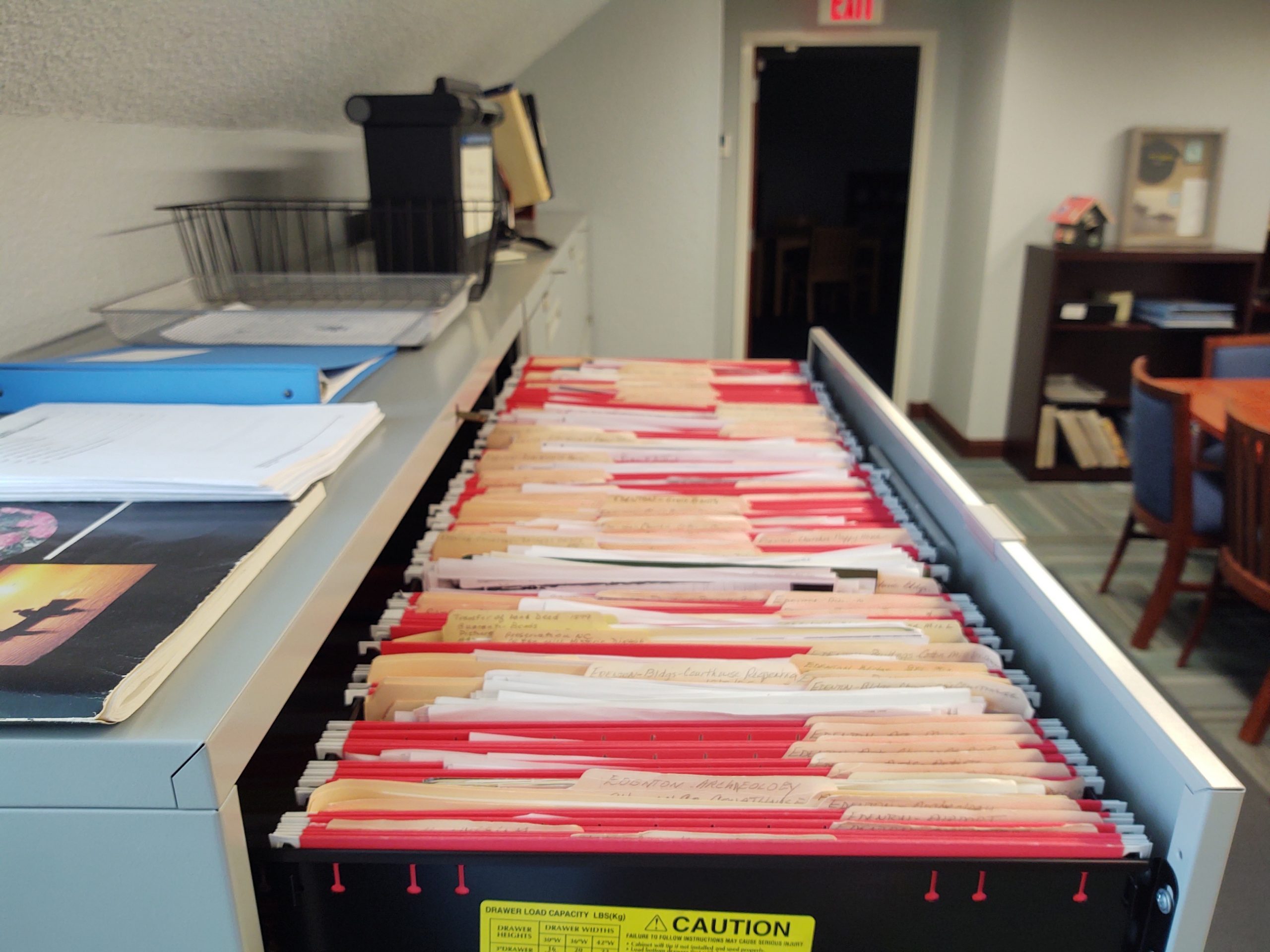

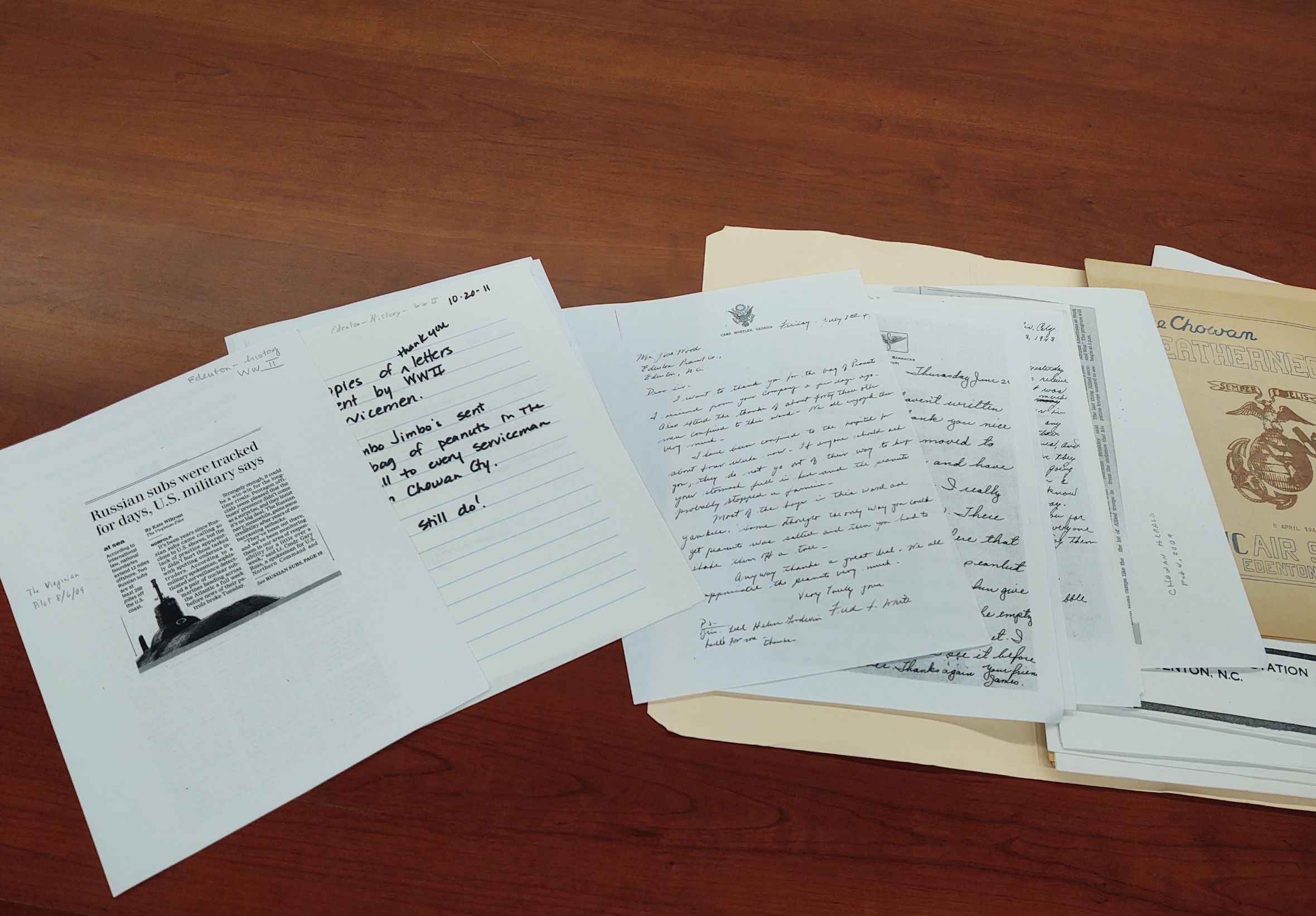

Vertical files are groups of subject-based materials often compiled over time to help an organization’s staff with frequent reference questions or research. Like the example above at Shepard-Pruden Library in Edenton, NC, they’re typically housed in filing cabinets. They are a good place to store items that wouldn’t necessarily be cataloged or accessioned (individually and formally documented by the institution) but are valuable for research. Inside you might find photographs, clippings, family trees, pamphlets, handwritten notes – but because the contents accumulate over time you can find any number of surprises inside.

Vertical files are groups of subject-based materials often compiled over time to help an organization’s staff with frequent reference questions or research. Like the example above at Shepard-Pruden Library in Edenton, NC, they’re typically housed in filing cabinets. They are a good place to store items that wouldn’t necessarily be cataloged or accessioned (individually and formally documented by the institution) but are valuable for research. Inside you might find photographs, clippings, family trees, pamphlets, handwritten notes – but because the contents accumulate over time you can find any number of surprises inside.

Vertical files are also the worst – for digitization that is. The same thing that makes them valuable for research – their convenience, their long term growth, and the variety of contents – makes them incredibly challenging to scan. If you’re interested in digitizing vertical files, we have suggestions! These have been compiled from our own experience at NCDHC along with the experiences of a number of our partners who kindly responded to a recent email asking for advice.

When facing full filing cabinets you may be tempted to dive in right at the beginning and get going, but we always suggest starting with a pilot project using a subset of materials. We can’t emphasize this enough! It’ll give you a sense of workflow, help you establish how you’re going to name and organize the scanned files, and uncover obstacles you didn’t anticipate. If it goes poorly, you can back out without losing a large investment. The suggestions below can be used for a pilot and for a full-fledged project.

Suggestion 1: Prep First, Thank Yourself Later

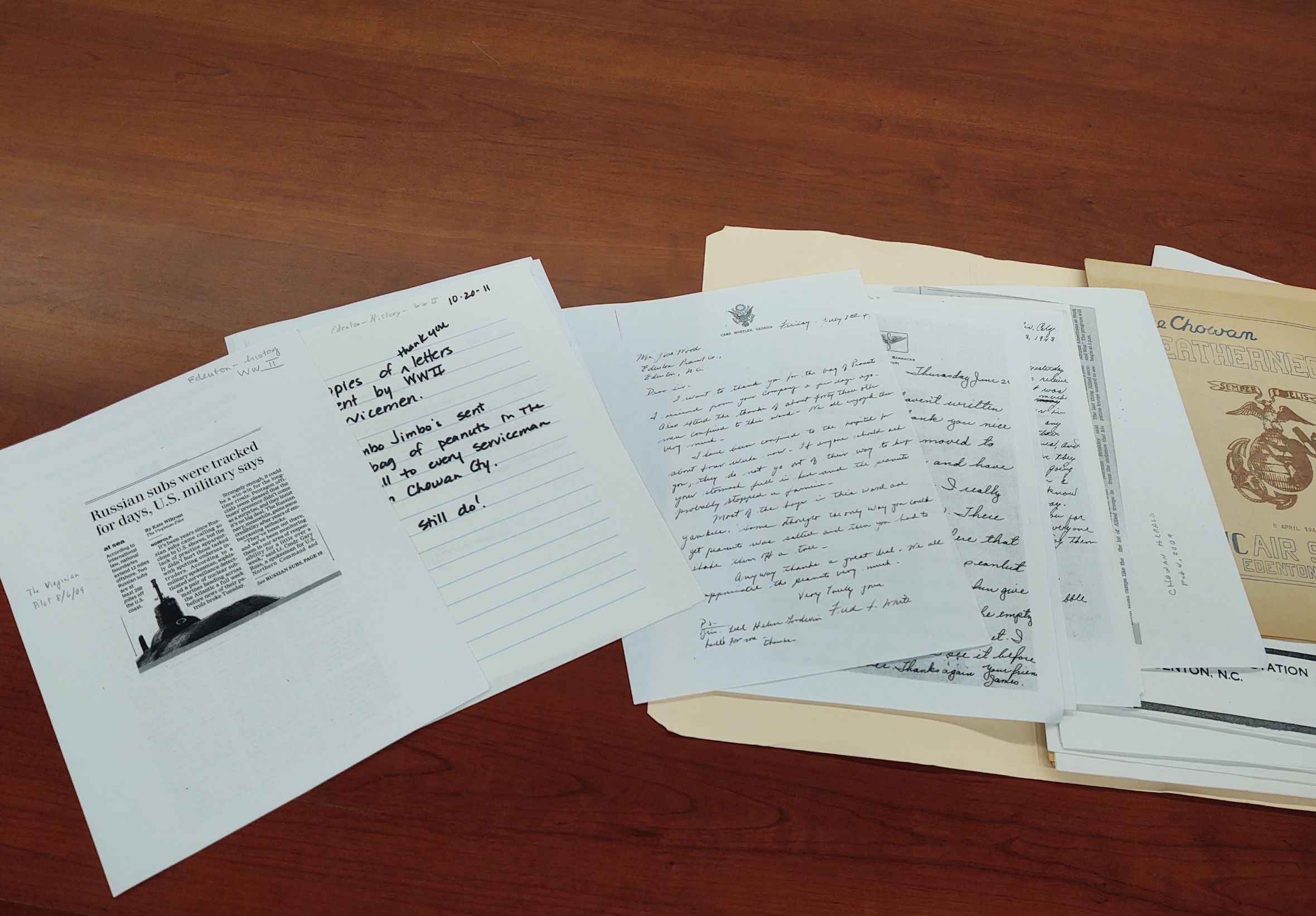

Here’s an example of a vertical file with newspaper clippings, letters, and publications about World War II. From the collection at Shepard-Pruden Library in Edenton.

Scan it all or be selective? Decide if you want to go from beginning to end or to be selective about what you’ll scan. There’s no right answer but each way has ups and downs. This decision will be subject to your users’ needs and your local resources.

Scan it all? Is there enough high value and unique content in your vertical files to warrant scanning everything? For example, some newspaper titles have been digitized in their entirety and are full text searchable (like those available at DigitalNC or Chronicling America) so you might decide that scanning clippings from those same papers is superfluous. As another example, many books published before 1924 in the United States are available online at the Internet Archive or through a simple search in your internet browser. If your files have a lot of book excerpts you may want to skip those.

Be selective? Being selective can be more time consuming and you may unintentionally miss items that would be of use, but it can be appropriate if you’re trying to simply scan items related to one or two topics or for a particular event. It is also a great option if you don’t have a lot of time or resources but want to help give access to high demand files.

First pass for organization. Go through the files in a first pass, during which you’ll assess the files’ contents, sort them in a way that will make scanning easier, and prepare the different formats for scanning. Here are some tasks to complete as you make a first pass:

- Pull out items to be cataloged separately. As your organization’s collection strategies have changed over time you may find materials within the files that should be pulled out and cataloged or accessioned independently. For example, perhaps you are a library where pamphlets were previously stuck in vertical files but are now cataloged and put on the shelf. These can be pulled out and dealt with separately.

- Weed. Take this opportunity to weed out duplicates and look for misfiled items.

- Group items with copyright or privacy concerns. I talk about this in more detail below, but if you plan to put these files online, you may want to skip scanning items that would be too risky or unethical to share online. You could put them towards the back of each file with a divider that indicates they should be either reviewed in more detail or skipped while scanning.

-

Ashlie, an NCDHC staff member, uses a microspatula to pry up staple legs. License: CC0

Remove staples and fasteners. The caveat here is that you should only do this with materials you’re sure you’re ready to scan. One partner mentioned that staff had removed staples and paperclips from a large quantity of files, but then the project got stalled. Because the vertical files were still in use, this led to papers being misfiled, shuffled out of order, and lost.

- Organize by type then by date. Within each file, organize individual items first by format of item, then by date. Group all of the photographs. Put like sized publications together. Group all of the single page items, all of the clippings. Putting like sized types together will speed up the workflow, saving time when scanning by streamlining your efforts at cropping. Once you’ve grouped things by type, within each group put things in date order (if dates are available). This will help you when you make the scans available.

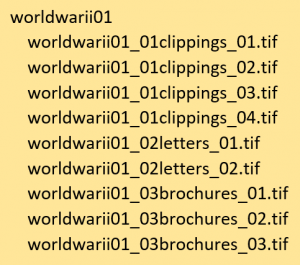

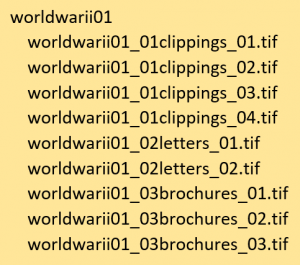

Suggestion 2: Prepare for the Digital Files

Unless you don’t have that many vertical files (or you have a LOT of time and help) think of each vertical file as a single unit. Here’s what I mean by this. If you have a vertical file about a popular local landmark called the “Turtle Log,” and it includes a few photos, some clippings, and a handwritten narrative, all of those scans would be kept together in a virtual group, folder, or album just as they are in real life. When you describe that group/folder/album either in an internal or online database, you’d describe the unit as a whole, rather than describing each individual photo, clipping, or narrative. This will save a ton of time.

With this in mind, you’ll want to think of a file naming scheme that will keep all of these digital groups organized. Thankfully, file systems mimic files in real life, with the use of folders. Make sure you have a consistent naming convention for files and folders that ensures everything sorts appropriately. On the right is a quick example of how you might decide to name your files. This example is very basic – you could choose to give more detail, include known dates. But note the numbers (01, 02, etc.) included that will make the files sort in order.

With this in mind, you’ll want to think of a file naming scheme that will keep all of these digital groups organized. Thankfully, file systems mimic files in real life, with the use of folders. Make sure you have a consistent naming convention for files and folders that ensures everything sorts appropriately. On the right is a quick example of how you might decide to name your files. This example is very basic – you could choose to give more detail, include known dates. But note the numbers (01, 02, etc.) included that will make the files sort in order.

Suggestion 3: Determine How You’ll Work with Additions

If you intend to keep these vertical files active after scanning, you’ll need to figure out how to denote what’s been scanned and what you’ll do with new additions to the files. A light pencil mark or some other non-permanent note on the back of all scanned items can signal what’s been scanned. Decide if you have the time and staff to scan new additions before filing new donations or if you plan to do that wholesale at a later date. It might also be helpful to have a marker of some sort that you can insert into the file cabinets that lets researchers and staff know about files that have been removed for scanning and whether or not they can still request them.

Suggestion 4: You Should Scan these In House. Or You Shouldn’t.

I wish I could give a single way forward here, but like so many things the answer to whether or not to outsource scanning depends on your situation. Here are a few considerations for the two routes.

Scanning in house. This gives you a lot of flexibility. You can work on the project over time. For active files, they’ll be close at hand if needed. Your staff will gain experience scanning, if they don’t already have it.

Unless you can afford an overhead scanner or camera mount setup, scanning vertical files on a flatbed or other multifunction machine will make a very long process a lot longer. Sheetfed scanners can speed things up a little but only for extremely uniform, non-unique materials that are in good shape. Because the project is large, if you don’t have dedicated scanning staff (or even if you do) be prepared for the contents of multiple file cabinets to take years to scan. You may also need to hire new staff or reskill current staff to do this work, trading this for other duties they currently complete.

Outsourcing scanning. Outsourcing can mean a quicker outcome because the organization doing the scanning will have dedicated workflows and equipment for high volume output. If you don’t have digitization expertise on staff, their expertise can be helpful for avoiding pitfalls.

Unless you are working with an organization that typically scans special collections, the variety of formats can be a challenge and frequently increase the cost. Companies that specialize in corporate files will claim attractively inexpensive prices for scanning but they are frequently used to working with homogenous typing or copy paper. Be sure to interrogate them regarding their expertise, showing them examples and even asking for a quote after they scan a subset. Make sure they offer digital files of a quality and in file formats that you can use into the future.

Suggestion 5: Decide About Your Access Priorities and the Rest will Follow

As we’re fond of saying, digitization is the easy part. Even in a project of this size and complexity, the scanning and preparation of the digital files is more straightforward then what comes next. Here are confounding factors to take into account when you consider how you’ll provide access to the digital vertical files.

Full Text Search

Full Text Search

Full text search greatly increases the usefulness of digital vertical files. It’s one of the most cited reasons for scanning them in the first place. To be able to search full text within a scanned document, you’ll need to run that digital file through software that recognizes the text and then either embeds it within the file or stores it separately. (Note that this will only happen with typewritten text – accurate automated recognition of handwriting isn’t widely available at this point.) Here are two different options:

- Some institutions choose the PDF format for their vertical files. Software like Adobe Acrobat (not to be confused with the freely available Adobe Reader) will recognize text within a PDF. However PDFs are made for easy transmission and sharing, not for longevity and quality. We recommend that you scan initially to a higher quality or lossless format, and then, if it fits your goals and resources, create derivatives like PDFs. The upside of PDFs is that many desktop and laptop computers can natively search across PDFs. This means you could have them searchable locally, say on a reading room computer, and not necessarily have to provide internet access.

- Alternatively, you can use a system that can store both the text recognized in an image and the image itself and then link them together. Some library or museum catalogs will do this, or you’ll need a content management system. This means additional ongoing costs and the need for technological infrastructure and expertise. But with these types of systems you can provide full text search of your files on the internet.

Copyright and Privacy

Copyright is one of the biggest confounding factors related to making vertical files accessible. Depending on how old your files are, it’s likely that there are materials in there that will be in copyright. If you want to post copyrighted materials on the internet, your organization will need to assess the amount of risk you’re willing to accept. Some items are riskier than others. Regardless, whoever is working on your vertical files will need training and the authority to determine what can and should go online and what should not. Here are a few resources to help get you started:

In addition to copyright, you should always consider privacy concerns. For some of the non-published items in your vertical files, the donations or additions were made with the expectation of local use by a single person or small group. Family history documents that discuss recent events are an example of the type of item you may judge to be too personal for broad consumption without the permission of the creator. There may be documents that share information about communities that would prefer they not be shared broadly. These are all good things to assess as you do your first pass.

Suggestion 6: Find Examples and Friends

Here are some examples of digitized vertical file collections online. These are large projects with a goodly number of staff and funding involved, so take that into account as you look. Note that the files are put online whole rather than breaking out individual items.

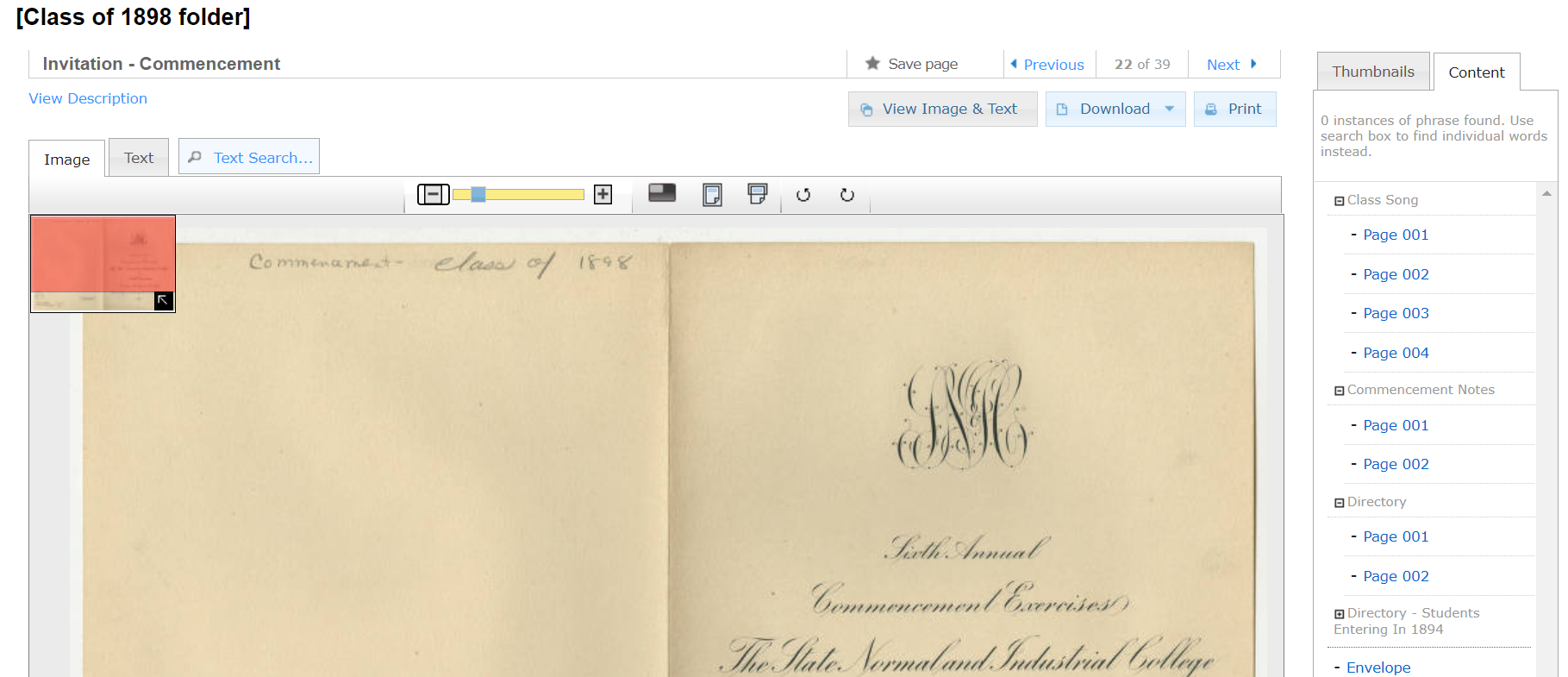

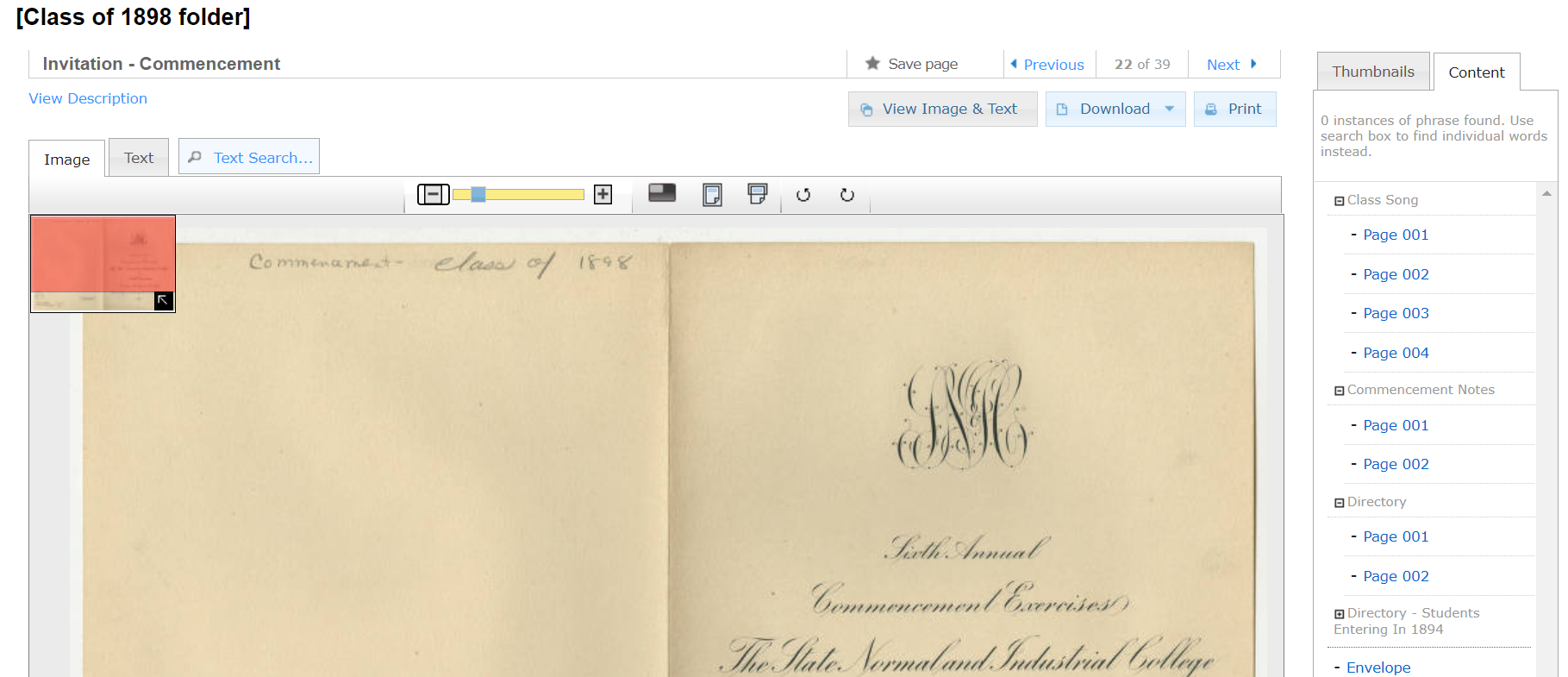

This first example comes from the Digital Collections of the University Libraries at UNC-Greensboro and showcases their “class folders.” UNC-G has done quite a bit with vertical files of various types, but this is a great example of folders that have a variety of items grouped by subject. These items are in a system called CONTENTdm, which is specifically designed to host special collections.

This invitation is one of a number of items in the vertical file entitled “Class of 1898.” You can see the item title at the top and a list of the different items inside on the right.

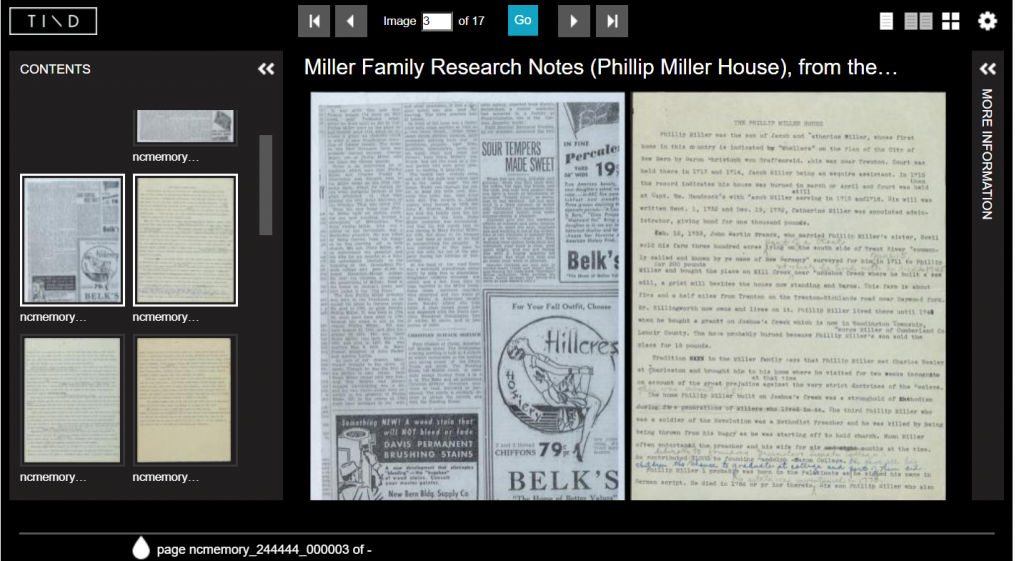

We’ve also done some vertical files at NCDHC, and you can take a look at an example here. This is from a large collection of vertical files shared by the Kinston Lenoir-County Public Library. Our system is called TIND.

This screenshot shows a large view of a newspaper clipping alongside a typewritten manuscript from the Sybil Hyatt Papers. To the left are thumbnails showing other items in this particular file.

Keep in mind that both of these systems are made for hosting large numbers of special collections items and, like a library or museum catalog, cost money and staff to maintain. While it’s outside of the scope of this article, you can take a look at another post we did regarding how to share your digital files.

For any digitization project, we heartily recommend trying to find friends and peers at area or regional organizations. Ask if they have vertical files or digitization projects (or both?!). A quick phone call or email can help you avoid duplication of effort, at the least, and may gain you advice or a collaboration. You can even choose to share staff or other resources, or collaboratively apply for funding. We also like to be friends! If you’ve made it this far and still want to digitize, but you have questions or would like additional advice, feel free to get in touch.

Vicki Coleman, Dean of Library Services at the F. D. Bluford Library, at North Carolina A&T State University

This year marks the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center’s 10th anniversary, and to celebrate we’ll be posting 10 stories from 10 stakeholders about how NCDHC has impacted their organizations.

Today’s 10 for 10 post is from Vicki Coleman, Dean of Library Services at the F. D. Bluford Library, at North Carolina A&T State University. We’ve partnered with NC A&T (Library home page | NCDHC contributor page) to digitize yearbooks, catalogs, and student newspapers. The Library also has their own extensive digital collections online, where you can find faculty research, agricultural history, and history about NC A&T. Read below for more about our partnership with NC A&T.

___

Happy 10th anniversary to the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center!

Over the past decade, the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center (NCDHC) has played a vital role in helping the F.D. Bluford Library at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University (NC A&T) ensure the success of its digital conversion projects. More specifically, the NCDHC’s digitization services have aided Bluford Library by providing the infrastructure to create thousands of preservation-quality digital images and other historical materials that are now accessible by students, faculty and researchers world-wide.

Working collaboratively with the NCDHC has opened opportunities for Bluford Library to give visibility to the wealth of history stored in its archive and to the many resources accessible from the DigitalNC website. Listed below are examples of how some digitized collections are used:

- The university’s digitized yearbooks (1939-2013), catalogs and bulletins (1895-2013) and student newspaper (1915-2010) serve as indexes, directing researchers to names, places, photos and historical events that helped shape the university, the surrounding Greensboro community, and the history of African-Americans with regards to higher education and the civil rights movement.

- In 2015, I oversaw the publication of NC A&T’s pictorial history book commemorating the university’s 125th anniversary. When it came to the digitization of some of our most brittle materials for inclusion in the book (e.g., minutes from an 1891 Board of Trustees meeting) it was the NCDHC that got it done.

- Over the past three years, James Stewart, the Archives and Special Collections librarian at Bluford Library, has taught more than 300 students how to access community histories about NC A&T and African-American history via the DigitalNC website.

- This past summer, Mr. Stewart and I conducted research pertaining to the naming of all the buildings and streets on the NC A&T campus. We were able to locate much of the historical information in the A&T Register, the NCA&T student newspaper that was digitized by the NCDHC and by searching the Newspapers collection on the DigitalNC website.

The NCDHC has advanced Bluford Library’s efforts to make historical materials accessible online by providing visionary guidance, high-level expertise and access to state of the art scanning equipment. I appreciate the great skills of the many individuals that make up the NCDHC and look forward to continuing a productive partnership with them. Congratulations to the NCDHC on its tenth anniversary and I await with pleasure another 10 years of remarkable achievements in increasing open access to the state’s cultural heritage.

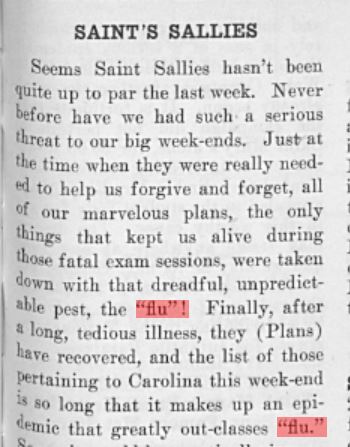

A couple of weeks ago UNC’s university archivist tweeted about finding articles in the Daily Tar Heel about a flu epidemic on UNC’s campus in early 1941. Intrigued – and figuring it was in no way contained to UNC’s campus – we did some digging in other newspapers on our site to find other stories about the epidemic’s impact on other campuses in NC at the time. A topic that is feeling quite relevant now, we found mentions scattered throughout the papers in January and February 1941 (for context – what would have been a year that started with an epidemic for these students and ended with the country involved in a World War) about how students were reacting to this sudden uptick in the flu.

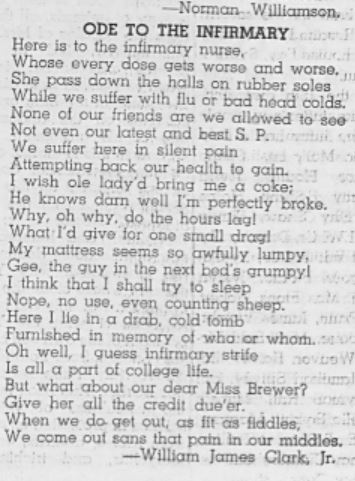

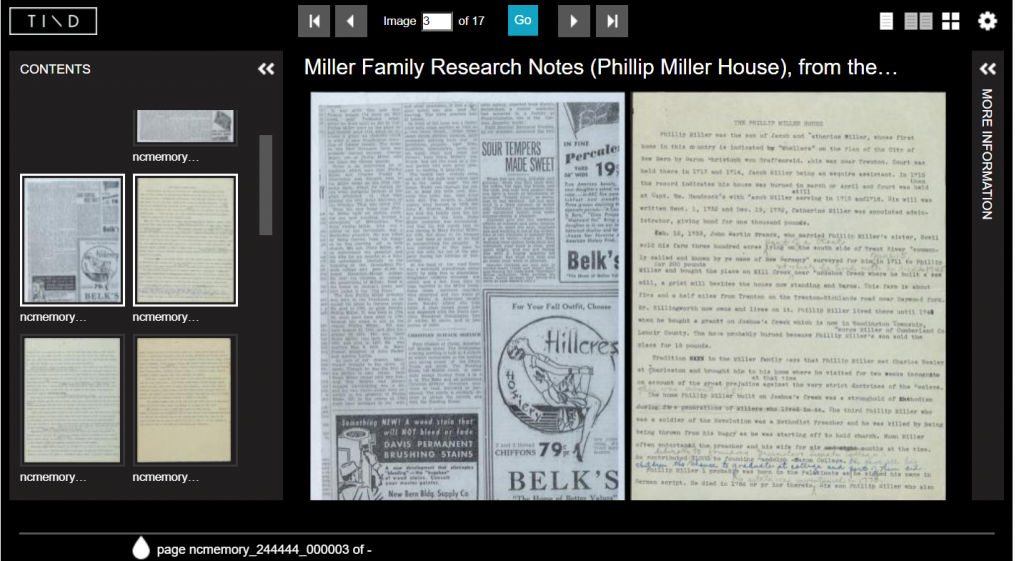

Several campuses seemed to have a newfound appreciation for the infirmary, with an “Ode the Infirmary” published in Mars Hill College’s student newspaper.

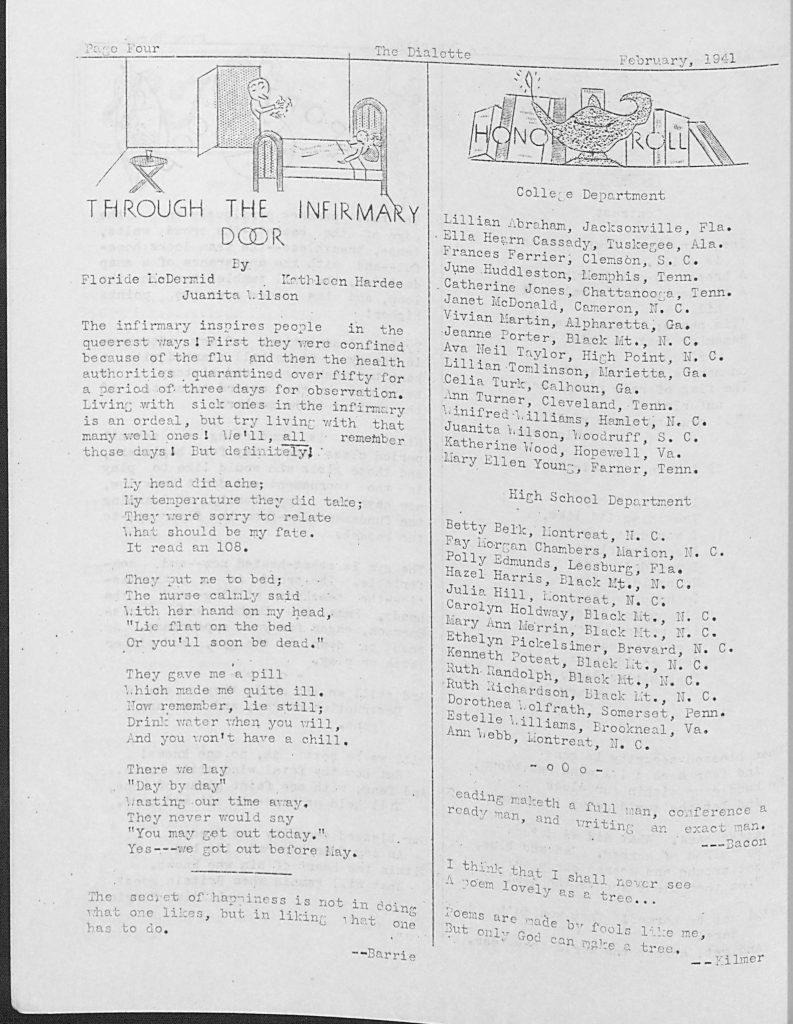

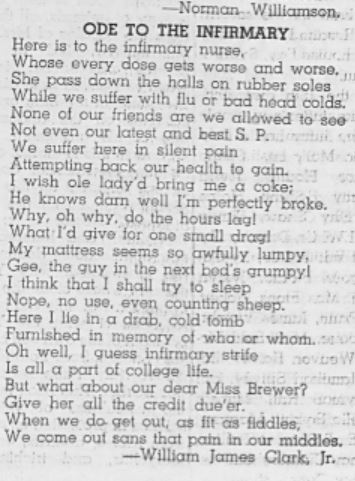

From the Montreat College paper, a look “Through the Infirmary Door”

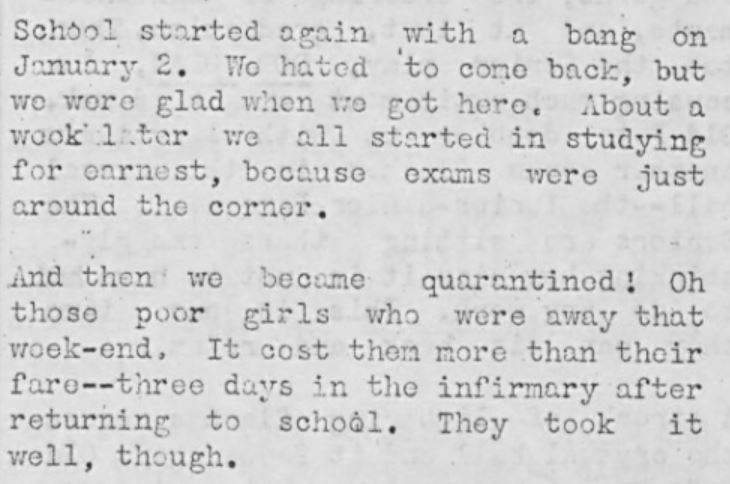

The social lives of the Belles of Saint Mary’s were put on hold for the flu that struck campus in mid January. Their society pages in their student newspaper detail such and the following flurry of activity as they were able to come out of quarantine.

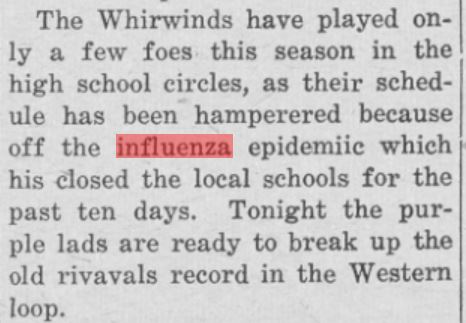

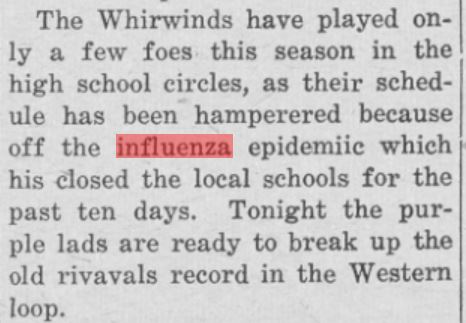

At the high school level, reports of basketball games and academic competitions were cancelled or put on hold as school was cancelled for several days to prevent the spread of the flu virus. Both the students at Greensboro High School and High Point School reported such.

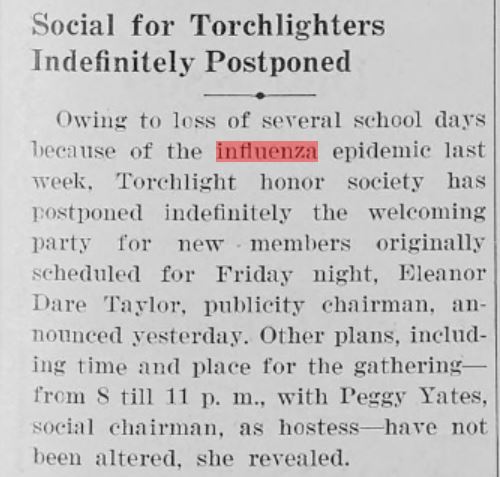

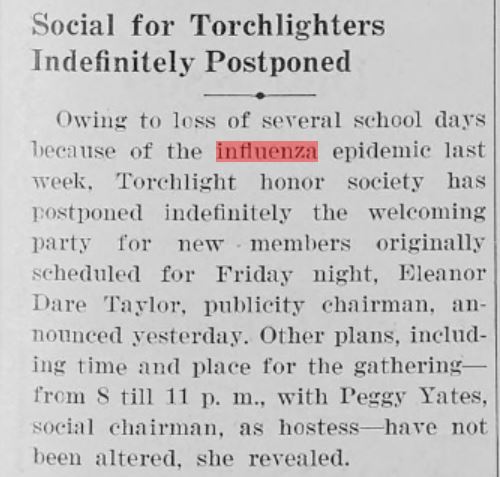

Other social and academic events were also cancelled – all citing the epidemic as the cause.

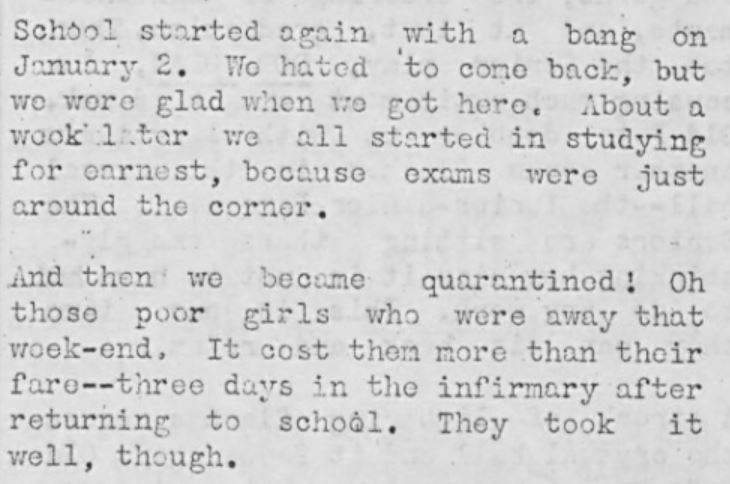

Other college campuses did not seem to have large effects from the flu but did report on students who were travelling from other areas of the state who then had to quarantine upon arrival on campus. For example, in an article in Montreat College’s student paper, they reported on students who had to quarantine upon arriving back to campus.

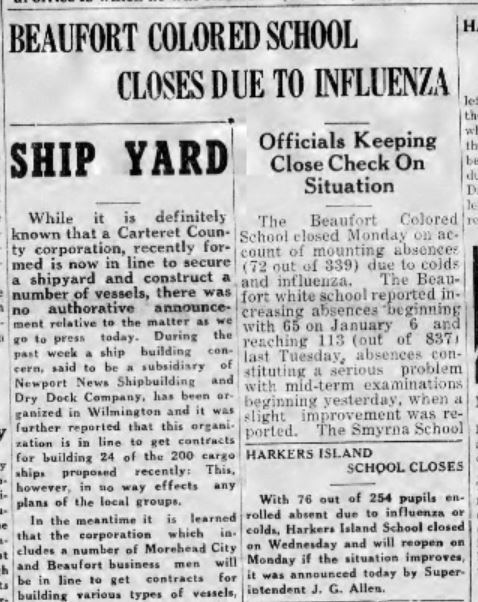

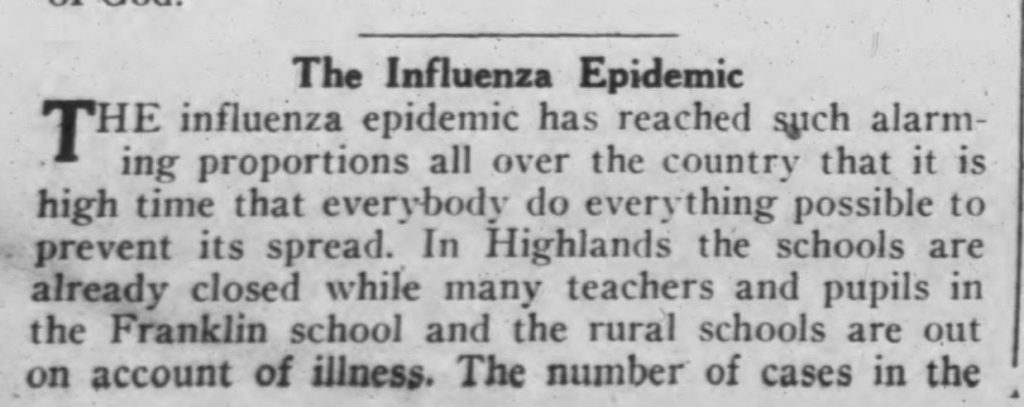

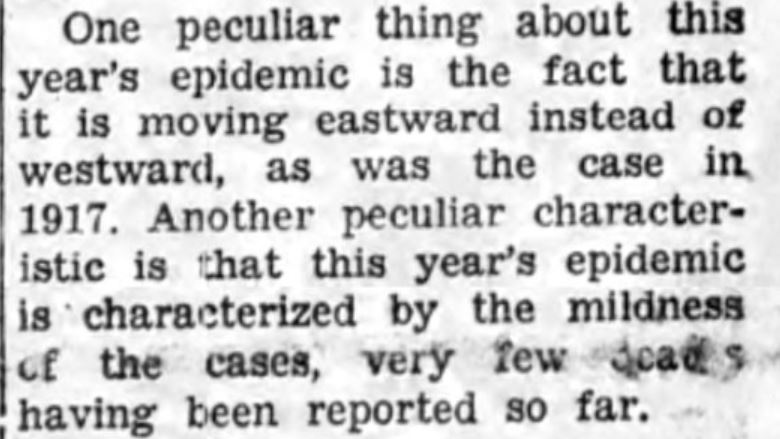

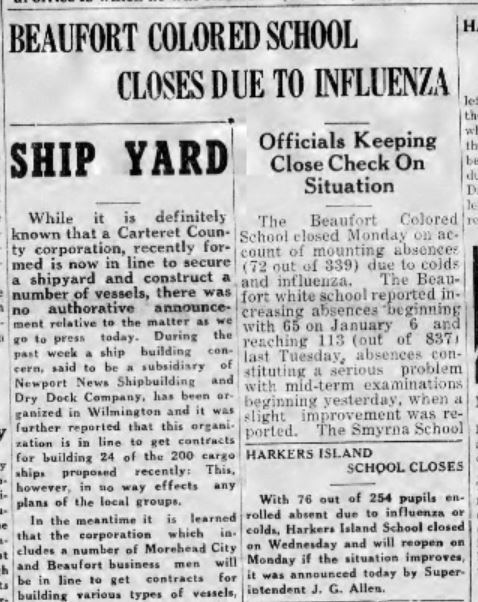

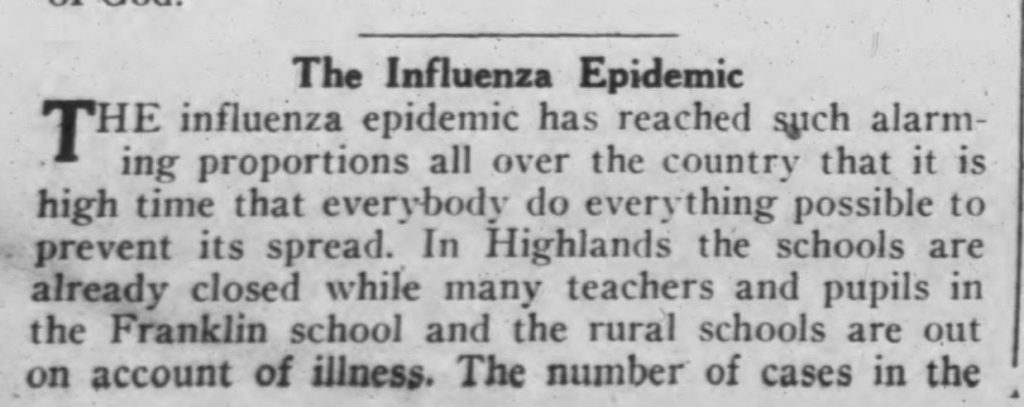

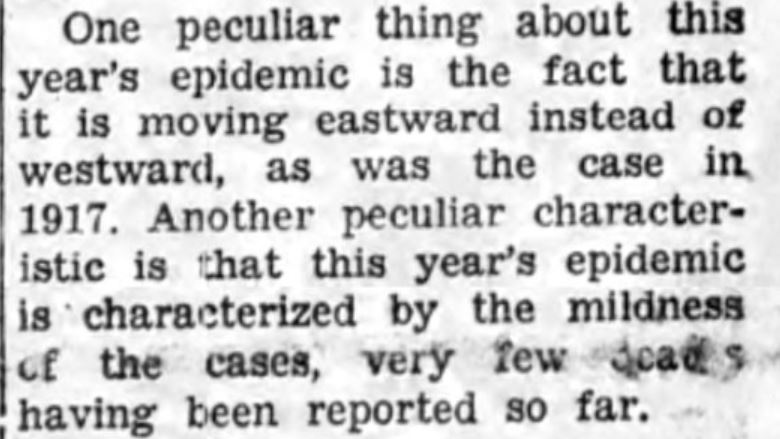

All in all, nothing quite as dramatic as what appears to have happened at UNC was going on at other North Carolina schools, perhaps another echo of what has happened in 2020. A brief perusal of the community papers from the time show that the flu epidemic was something affecting the whole state for sure, with mentions of it in papers from as far east as Beaufort, NC and as far west as Franklin, NC in Macon County.

Clipping from The Beaufort News , January 16, 1941

Clipping from The Franklin press and the Highlands Maconian, January 23, 1941

Several articles note that this particular epidemic was moving from the western part of the state to the eastern part of the state, which was apparently unusual, and overall cases had been fairly mild (which likely explains in part why it rarely pops up as an event in history).

January 22, 1941 issue of the State Port Pilot discussing the effects of the flu across the state.

To explore our over 1 million pages of digitized newspapers yourself, visit our North Carolina Newspapers page and read here about how colleges in NC responded to the 1918 Spanish Flu pandemic.

It’s DigitalNC.org’s 10th birthday! Though we had hoped to be in the office celebrating, we’re still taking time to look back at years of hard work and the collaborative spirit that makes the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center (NCDHC) what it is!

It’s DigitalNC.org’s 10th birthday! Though we had hoped to be in the office celebrating, we’re still taking time to look back at years of hard work and the collaborative spirit that makes the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center (NCDHC) what it is!

To date, NCDHC has partnered with 273 libraries, museums, alumni associations, archives, and historic sites in 98 of North Carolina’s 100 counties and we’re growing all the time. Our website currently includes 4.2 million images and files. We share this accomplishment with every institution we’ve worked with. We’d never have gotten to 10 years without staff (permanent, temporary, and student!), our partners, or the network of colleagues all over North Carolina who have encouraged, advised, and supported our work.

As we approached our anniversary, we realized that our website lacked a synopsis of how NCDHC came to be, and our history. So read on for a brief look at how we got started and our major milestones.

Our History

The North Carolina Digital Heritage Center was one outcome of a comprehensive effort by the state’s Department of Cultural Resources (now the Department of Natural and Cultural Resources) to survey and get a broad overview of the status of North Carolina cultural heritage institutions. That effort was entitled NC ECHO (North Carolina Exploring Cultural Heritage Online) and was funded by the Institute of Museum and Library Services (which also supports us – thanks IMLS). A major goal of NC ECHO was a multi-year needs assessment. NC ECHO staff visited hundreds of cultural heritage institutions throughout the state to collect data and interview curators, librarians, volunteers, archivists, and more. Many of our partners still remember their visits!

Data collected at these site visits was combined with survey responses to reveal a “state of the state,” summarized in a 2010 report, cover pictured at right. The assessment revealed a lot but, specific to digitization, staff found that nearly three-quarters of the 761 institutions who completed the survey had no digitization experience or capacity. Members of the Department of Cultural Resources (which includes the State Library, State Archives, and multiple museums and historic sites) began brainstorming with other area institutions about a way to help efficiently and effectively provide digitization opportunities. While the NC ECHO project offered digitization grants, workshops, and best practices, an idea emerged of a centralized entity that could assist institutions that didn’t have the capacity to do the work in house. The State Library of North Carolina and UNC-Chapel Hill Libraries joined together to create such an entity: the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center. The Center would be located in Chapel Hill, taking advantage of its central location and the digitization equipment and expertise already available in Wilson Special Collections Library. The State Library would provide funding, guidance, and ongoing promotion and support of the Center’s services.

Data collected at these site visits was combined with survey responses to reveal a “state of the state,” summarized in a 2010 report, cover pictured at right. The assessment revealed a lot but, specific to digitization, staff found that nearly three-quarters of the 761 institutions who completed the survey had no digitization experience or capacity. Members of the Department of Cultural Resources (which includes the State Library, State Archives, and multiple museums and historic sites) began brainstorming with other area institutions about a way to help efficiently and effectively provide digitization opportunities. While the NC ECHO project offered digitization grants, workshops, and best practices, an idea emerged of a centralized entity that could assist institutions that didn’t have the capacity to do the work in house. The State Library of North Carolina and UNC-Chapel Hill Libraries joined together to create such an entity: the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center. The Center would be located in Chapel Hill, taking advantage of its central location and the digitization equipment and expertise already available in Wilson Special Collections Library. The State Library would provide funding, guidance, and ongoing promotion and support of the Center’s services.

At its beginning, the Center’s staff digitized small collections of college yearbooks, needlework samplers, postcards, and photographs and made them available through DigitalNC.org. They went to speak with organizations interested in becoming partners, and began taking projects for digitization. Here’s a list of NCDHC’s earliest partners, who came on board during late 2009 and 2010.

Though we’re not positive of the exact date, we believe DigitalNC.org launched on or near May 12, 2010. Here’s a look at that original site!

In 2011, word about the Center spread. Staff started responding to demand from partners, incorporating newspaper digitization. In late 2012, also in response to popular demand, the Center began digitizing high school yearbooks. Yearbooks and newspapers are some of the most viewed items on DigitalNC, and they remain a significant portion of our work to this day.

In 2013, NCDHC joined the Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) as North Carolina’s “service hub.” The DPLA collects information from digitized collections all over the nation and provides it together in one searchable interface at dp.la. Because of our participation, users can browse and search for collections from North Carolina alongside items from institutions around the country.

Throughout the years, we’ve tried to expand services to fit our partners’ goals. In 2015, we trialed an audiovisual digitization project that incorporated the first films into DigitalNC. Today, we partner with the Southern Folklife Collection at Wilson Special Collections Library to provide audio digitization on an ongoing basis. In 2016, we added a new partner category – alumni associations – to support more digitization of African American high school yearbooks and memorabilia. The following year, we announced a focus on digitization of items documenting underrepresented communities. We also started going on the road with our scanners! For institutions that don’t have the staff time or resources to travel to Chapel Hill, we offer to come for a day or two and scan on site.

2018 and 2019 saw several major milestones. We were nationally recognized as an Institute of Museum and Library Services National Medal finalist, and we began a major software migration. Both were a tribute to the size and extent of our operation, though in different ways. As we’ve approached our 10th anniversary we’ve focused on working with partners in all 100 of North Carolina’s counties. Whether you’re rural or metropolitan, we believe your history is important and should be shared online.

2018 and 2019 saw several major milestones. We were nationally recognized as an Institute of Museum and Library Services National Medal finalist, and we began a major software migration. Both were a tribute to the size and extent of our operation, though in different ways. As we’ve approached our 10th anniversary we’ve focused on working with partners in all 100 of North Carolina’s counties. Whether you’re rural or metropolitan, we believe your history is important and should be shared online.

One of the ways we’re commemorating this anniversary is to ask our partners and stakeholders how they think we’ve impacted them and their audiences. Join us here on the blog in the second half of 2020 as we share these brief interviews, reflect, and celebrate. Thank you for reading, enjoy the site, and here’s to another 10 years of making North Carolina’s cultural heritage accessible online!

Alabama native Emmylou Harris spent time in North Carolina in the mid 1960s when she was attending the University of North Carolina at Greensboro on a drama scholarship. This photo, from the

Alabama native Emmylou Harris spent time in North Carolina in the mid 1960s when she was attending the University of North Carolina at Greensboro on a drama scholarship. This photo, from the