Urban Development and Renewal

Document Presets

To download, choose the "Save as PDF" option when asked to choose a printer.

Primary Source Set

Urban Development and Renewal

Beginning in 1949, the federal government provided funds for cities across the United States to seize and demolish buildings in “blighted” areas with the intention of inviting in new industries and improved housing. Neighborhoods with a high percentage of Black residents, many of whom were displaced by redevelopment efforts, were disproportionately targeted by urban renewal. This set uses photographs, maps, pamphlets, scrapbooks, newspaper articles, and government records to depict the impact of urban renewal on communities throughout North Carolina, with a focus on two neighborhoods in Durham and Raleigh.

Proceed with caution and care through these materials as the content may be disturbing or difficult to review. Please read DigitalNC’s Harmful Content statement for further guidance.

Time Period

1954-1974

Selected Sources

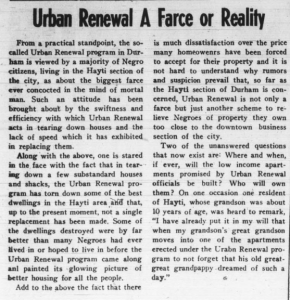

"Urban Renewal A Farce or Reality," The Carolina Times

Durham, N.C. (Durham County), 1965

Hayti, a neighborhood in Durham made up of mostly Black residents, was one of many areas in North Carolina to experience urban renewal in the 1960s. In this article from Black-owned newspaper The Carolina Times, the author discusses some of the redevelopment problems felt by the Hayti community, including dissatisfaction with property prices given to homeowners and frustration over the lack of new low-income housing for those whose homes were demolished.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Durham County Library, State Archives of North Carolina, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

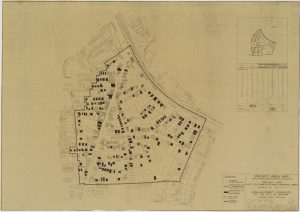

Project Area Map Structural Environmental Condition

Durham, N.C. (Durham County), 1961

During the 1960s, the Durham Redevelopment Commission produced a series of maps that showed areas slated for urban renewal. The purposes of the maps varied, as some displayed project plans, while others identified the current conditions of the mapped location. This map outlines the buildings to be acquired by the city and surveys their structural environmental conditions. The map labels the structures as either standard with no deficiencies, substandard due to environment deficiencies only, or substandard due to building deficiencies.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Durham County Library

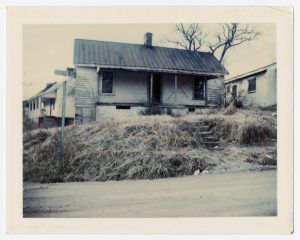

618 South Street, Durham, N.C.

Durham, N.C. (Durham County), 1970

The urban renewal efforts in Durham during the 1960s and early ‘70s included the construction of the Durham Freeway (NC-147), which was built to lessen downtown traffic and to better connect the Research Triangle area. The house pictured here has a red “X” marked on the front, indicating that it is ready to be demolished to make room for the freeway.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Durham County Library

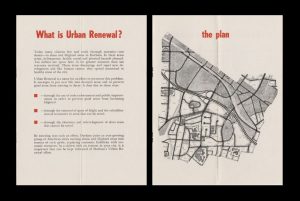

Durham Urban Renewal Brochures and Booklets

Durham, N.C. (Durham County), 1962

This booklet is one of several pamphlets distributed to Durham citizens during redevelopment in the city. Its contents include a definition and explanation of urban renewal, a map of the Hayti area that outlines when and where renewal projects would take place, and a Q&A section for residents. Additionally, the booklet contains a map that depicts how Hayti might look in the future, after renewal. Areas that were to be impacted by urban renewal are described negatively, with one page comparing the “blighted” neighborhoods to cancer.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Durham County Library

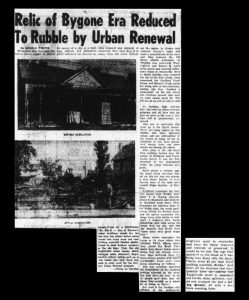

"Relic of Bygone Era Reduced To Rubble by Urban Renewal," The Carolina Times

Durham, N.C. (Durham County), 1963

In addition to displacing families, urban renewal caused the destruction of important and historic community buildings, such as the “old Boys’ Club” in the Hayti neighborhood. This article from Black-owned newspaper The Carolina Times features the “before” and “after” pictures of the demolition of the structure and includes details on the value of the old Boys’ Club to Hayti residents. According to the text, the building (almost a century old at the time of its destruction) was a place for social gatherings, special events, and other community activities.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Durham County Library, State Archives of North Carolina, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

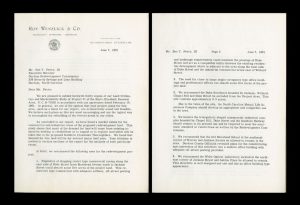

Project 1 Land Use Survey

Durham, N.C. (Durham County), 1961

Sent to the Durham Redevelopment Commission, this survey report advised the commission on the utilization and marketability of the land in the Hayti neighborhood post-renewal. The first two pages of the report, pictured here, discuss the potential for industrial and commercial development in the area. It also provides recommendations for the redevelopment projects, suggesting which buildings should or should not be acquired.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Durham County Library

511 East Glenn Street, Durham, N.C.

Durham, N.C. (Durham County), 1963

As urban renewal efforts in Durham continued, the city’s redevelopment commission began to appraise the structural condition and financial value of Hayti properties located in the urban renewal zone. This photograph of 511 East Glenn Street is just one element of that house’s appraisal record. Other parts of appraisal include information about the property, such as a sketch of the house’s dimensions and an estimated value for the property. Additionally, the document contains a remark about the building’s condition that reads: “very old, obsolete duplex.”

Contributed to DigitalNC by Durham County Library

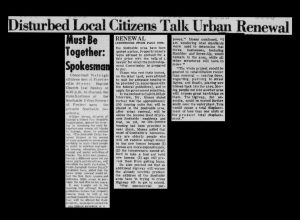

"Disturbed Local Citizens Talk Urban Renewal," The Carolinian

Raleigh, N.C. (Wake County), 1969

As urban renewal projects progressed in Raleigh, residents of the impacted areas began to voice their issues with redevelopment in community gatherings. This article from Black-owned newspaper The Carolinian discusses a meeting held by concerned citizens of Raleigh, who talked over some of the ramifications of urban renewal in the city’s Fourth Ward/Southside neighborhood. The discussion was led by William Moses, director of the United Poor People’s Organization of Raleigh. Moses and others expressed concerns about the housing issues caused by redevelopment, including a lack of new low-income apartments and delays in homeowners receiving quotes for the price of their houses. At the end of the article, Moses wished the urban renewal project in Raleigh was more “rehabilitation than removal.”

Contributed to DigitalNC by Olivia Raney Local History Library

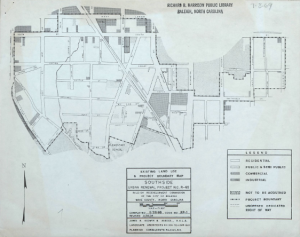

Existing Land Use and Project Boundary Map

Raleigh, N.C. (Wake County), 1968

This map from the Raleigh Redevelopment Commission outlines the boundary for the urban renewal project in the Fourth Ward neighborhood (referred to here as Southside). Additionally, the map depicts how land was used in Fourth Ward before redevelopment began. Most areas were residential.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Wake County Public Libraries

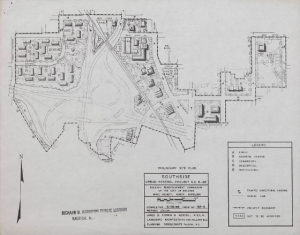

Preliminary Site Plan

Raleigh, N.C. (Wake County), 1968

While some redevelopment maps depicted the existing land use of areas where urban renewal was planned, others showed proposals for land use. This map imagines the Fourth Ward area post-renewal, displaying institutional, residential, and commercial sections, as well as public spaces and a shopping center. It also shows a large traffic interchange.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Wake County Public Libraries

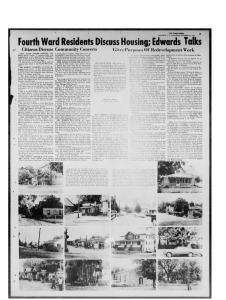

"Fourth Ward Residents Discuss Housing; Edwards Talks"

Raleigh, N.C. (Wake County), 1966

When urban renewal for the Fourth Ward neighborhood of Raleigh was first proposed, residents’ reactions to the news were varied. This article from Black-owned newspaper The Carolinian includes short interviews with thirteen Fourth Ward citizens who shared their perspectives on renewal. While some of the residents expressed concern or uncertainty about urban renewal, others hoped for redevelopment to happen in Fourth Ward.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Olivia Raney Local History Library

"What is Urban Renewal," The Jones County Journal

Trenton, N.C. (Jones County, Lenoir County), 1961

This article from The Jones County Journal, aimed at residents of the town of Kinston, attempts to explain and clarify urban renewal. Using a Q&A format, the article answers questions like “what does a project cost?” and “what happens after the land is acquired?” The article also claims that urban renewal does not cause the seizure of land, and that redevelopment commissions buy houses at prices “much more than fair to the property owner.”

Contributed to DigitalNC by Kinston-Lenoir County Public Library, Neuse Regional Library

"When A Town Really Works For A Finer Carolina!"

Zebulon, N.C. (Wake County), 1954

During the 1950s, the Carolina Power and Light Company encouraged cities and towns across North Carolina to improve their communities by competing for cash prizes in what was called the Finer Carolina contest. Pictured here is an advertisement for the contest in The Zebulon Record newspaper. The ad explains the potential benefits of participating in Finer Carolina and claims that the program will create “a happier, more prosperous town.”

Contributed to DigitalNC by Little River Historical Society

Asheboro Finer Carolina Scrapbook

Asheboro, N.C. (Randolph County), 1954

In 1954, the city of Asheboro took part in the Carolina Power and Light Company’s Finer Carolina contest, in which cities and towns across North Carolina made improvements to their communities for cash prizes. A regular participant in the contest, the city of Asheboro created scrapbooks like this one to document each step of community improvement. Pictured here is a page from the “beautification” section of the scrapbook. This page shows before and after photographs of a building called the old Central Hotel, which was demolished because it was “unsightly” and “shabby and dilapidated.” According to the scrapbook, the land was later graded for use as a parking lot.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Randolph County Public Library

For a Finer Carolina, Burgaw North Carolina's Finest

Burgaw, N.C. (Pender County), 1954

In 1954, the town of Burgaw participated in the Finer Carolina contest and created a scrapbook that detailed each community improvement, such as a parade that celebrated the town’s 75th anniversary. Included in the scrapbook is this photo of a parade float from the Carolina Power and Light Company, which is decorated with the slogan, “Let’s Make Our Town Carolina’s Finest.”

Contributed to DigitalNC by Pender County Public Library

Background

Throughout the 1950s and 1960s, the term “urban renewal” was used to describe the redevelopment efforts passed into law by the Housing Act of 1949. The Act spawned a federal program that funded the seizure and demolition of “blighted” or “slum” neighborhoods for redevelopment purposes. Although the intended goal of urban renewal was to build better housing and revitalize urban areas, redevelopment efforts disproportionately targeted predominantly Black neighborhoods. In North Carolina, Black communities in cities like Durham and Raleigh were displaced from their homes in the name of urban renewal, though many of the redevelopment promises made to those communities never arrived.

Urban renewal came to Durham’s Hayti neighborhood in the early 1960s, when the commission that oversaw the city’s redevelopment began to map the area, evaluating elements like the structural condition of buildings and creating plans for future land use. The Durham Redevelopment Commission also conducted appraisals on properties in Hayti to estimate their value. As the project progressed, the Commission distributed pamphlets that explained urban renewal as a way to revitalize “blighted” areas, promising that better infrastructure and new housing would come to Hayti. Initially, many of Durham’s Black citizens supported urban renewal, as they believed that the federal funds would be used to benefit their communities. City officials, eager to use those federal funds with little oversight, also approved of urban renewal. With the construction of the Durham Freeway (NC-147) included in redevelopment plans, white business owners who hoped that the freeway would relieve traffic congestion were also supportive of renewal efforts.

Urban renewal forced citizens to leave their residences. Although the Durham Redevelopment Commission provided compensation to Hayti homeowners before they seized and demolished their houses, many residents felt that the prices they received were unfair. Residents who were displaced from rental housing experienced similar frustrations about the lack of new low-income apartments in Hayti, which the Durham Redevelopment Commission had said they would build. Low-income housing and other redevelopment promises made by the Commission never materialized, even many years after urban renewal began. Similar events transpired in Raleigh, where redevelopment displaced residents of a predominantly Black neighborhood called Fourth Ward (also referred to as Southside).

While the Housing Act allowed redevelopment to occur across the United States and in North Carolina, this primary source set places its main focus on the areas of Hayti and Fourth Ward to illustrate how urban renewal impacted primarily Black neighborhoods, causing people to lose their homes, businesses, and communities for little in return.

Discussion Questions

While the existing land use map depicts Raleigh’s Fourth Ward neighborhood before urban renewal, the preliminary site plan map shows a proposal for land use after redevelopment. Compare the two maps, making sure to notice how the types of land (residential, commercial, industrial) change from one to the other. What changed? What do the changes indicate about what the Durham Redevelopment Commission valued?

What did urban renewal attempt to accomplish? What did it actually accomplish in neighborhoods like Hayti and Fourth Ward? Do the goals and outcomes of urban renewal conflict with each other?

Consider this article from The Carolinian, in which residents of the Fourth Ward neighborhood express their opinions on urban renewal potentially occurring in the area. What are their perspectives on renewal? What may have caused residents to be supportive of or concerned by urban renewal? Do you think the opinions of some residents changed after redevelopment occurred in Fourth Ward, and if so, why?

Review this booklet distributed by the Durham Redevelopment Commission. How does the booklet describe and portray urban renewal? How does it differ from the portrayal in other sources, like the one in this The Carolina Times article?

The Asheboro Finer Carolina scrapbook features before and after photos of many old buildings that were demolished as part of the community improvement contest. The scrapbook refers to the effort as “beautifying.” How does the scrapbook describe the buildings that were destroyed? In what ways does Finer Carolina relate to urban renewal?

In this The Carolinian article, the director of Raleigh’s United Poor People’s Organization refers to urban renewal as a removal: “The whole project should be geared to rehabilitation rather than removal.” In contrast, this The Jones County Journal article claims that “nobody’s property is ‘stolen, seized, or confiscated’” during urban renewal. Why do the two articles hold such different views on urban renewal? What does each perspective indicate about that era’s attitude on the well-being of communities, particularly Black communities?

Several sources in this set use terms like “blighted,” “decayed,” and “slum” to describe areas that were set to undergo urban renewal. This booklet states that such places were a “cancer.” Considering that redevelopment mostly occurred in low-income Black neighborhoods, what do these negative descriptions reveal about the people that supported urban renewal? What do the descriptions indicate about urban renewal as a program?

Take a look at aerial photographs of Hayti here. How did the area change from the 1950 photo to the one from 1972? Considering the aerial photos and the sources on Hayti in this set, how do you imagine the impact of urban renewal is still felt today?

These materials were compiled by Isabella Walker. Updated March 2025.

https://www.digitalnc.org/primary-source-sets/urban-development-and-renewal/

This document was prepared for print on August 29, 2025.