Native Americans in North Carolina, 1900 to the Present

Document Presets

To download, choose the "Save as PDF" option when asked to choose a printer.

Primary Source Set

Native Americans in North Carolina, 1900 to the Present

Today, North Carolina is home to over 130,000 Native Americans and eight state-recognized tribes. Native American communities have been severely impacted since the first instances of European colonization in the 1600s, but the 20th century brought particular kinds of legislation, policies, and media representations that have affected the Indigenous peoples of North Carolina. With materials dating between 1900 and the present, this primary source set uses photographs, maps, catalogs, newspaper articles, and pamphlets to illustrate the challenges faced by North Carolina Native Americans and the efforts made to preserve their cultures and communities.

Proceed with caution and care through these materials as the content may be disturbing or difficult to review. Some sources include racist portrayals of Native Americans or contain descriptions of violence and discrimination enacted upon Native Americans. Please read DigitalNC’s Harmful Content statement for further guidance.

Time Period

1920-2019

Selected Sources

"Committee has begun meeting on strategies to attain goals of federal recognition for Lumbee," The Carolina Indian Voice

Pembroke, N.C. (Robeson County), 1999

Although the Lumbee tribe was recognized by the federal government in the Lumbee Act of 1956, they have yet to receive full federal recognition. As a result, the Lumbee do not receive the same benefits that fully recognized tribes receive, like financial assistance and help in developing tribal governments. This article from Lumbee newspaper The Carolina Indian Voice discusses the formation of a Lumbee-led Federal Recognition Commission and the continued fight of the Lumbee community for full tribal recognition from the federal government.

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

"Commission Of Indian Affairs Proposed," The Smoky Mountain Times

Bryson City, N.C. (Swain County), 1997

Before the North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs was officially established in 1972, its creation was first proposed in legislation brought to the state’s General Assembly in 1971. This article from The Smoky Mountain Times discusses the proposal to create the commission. It states that the commission would help provide aid for Native Americans, prevent hardships they endure, and assist their communities with economic and social growth. Additionally, the commission would advocate for Native Americans’ right to participate in their cultural and religious practices.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Fontana Regional Library, Western Carolina University, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

"Cherokee Indian Vote May be Thrown Out," The Greensboro Patriot

Greensboro, N.C. (Guilford County), 1920

This article from The Greensboro Patriot describes a threat to the votes of Cherokee tribal members in an election in Jackson County. In 1920, Native American voting rights were not yet federally protected. Therefore, voting officials in the county legally had the ability to determine if Native people could participate in the election.

Native Americans were officially considered citizens as of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. However, many Natives continued to experience disenfranchisement until the 1965 Voting Rights Act prohibited states from engaging in discriminatory voting practices.

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

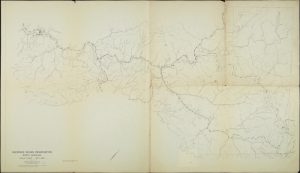

Cherokee Indian Reservation, North Carolina

Bryson City, N.C. and Cherokee, N.C. (Swain County, Jackson County), 1963

Today, most members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee still reside in the land depicted in this map, also known as the Qualla Boundary. While the map is titled “Cherokee Indian Reservation,” the Qualla Boundary is not a reservation, as tribal members own eighty percent of the land. Additionally, the land in the Qualla Boundary is held in a trust, meaning that it can only be sold to members of the Cherokee tribe.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Western Carolina University

"The History Introduction," The Lost Colony Souvenir Program

Manteo, N.C. (Dare County), 1947

Since 1937, an outdoor play called The Lost Colony has been put on in Manteo, North Carolina almost every summer night. Based on the failed English attempt to colonize Roanoke Island, the play has a history of using skin-darkening makeup and casting non-Indigenous actors to play Native American characters. This playbill from the 1947 season includes a section on the history that informs much of the play. The writing describes the English colonization efforts with a positive viewpoint, but portrays Native Americans stereotypically with terms like “savage.”

Contributed to DigitalNC by Roanoke Island Historical Association

"The Lost Colony is Back and Better Than Ever," The Lost Colony Souvenir Program

Manteo, N.C. (Dare County), 2021

Since 1937, an outdoor play called The Lost Colony has been put on in Manteo, North Carolina almost every summer night. Based on the failed English attempt to colonize Roanoke Island, the play has a history of using skin-darkening makeup and casting non-Indigenous actors to play Native American characters. This section of the The Lost Colony playbill from the 2021 season acknowledges the play’s former racist practices and discusses how the play has changed to better represent its Native American characters.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Roanoke Island Historical Association

"Cherokee Nation's Story Told in North Carolina Drama," North Carolina Catholic

Cherokee, N.C. (Swain County, Jackson County), 1952

This article from the North Carolina Catholic newspaper advertises Unto These Hills, an outdoor drama shown in Cherokee, North Carolina. The play tells the history of the Cherokee people from their first contact with Europeans to the years after the Trail of Tears.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Catholic Diocese of Raleigh

Goins School Students

Goins Town, N.C. (Rockingham County), 1949

This photograph shows Native American students of Goins School standing in front of a bookmobile that provided them with books. Due to segregation policies in North Carolina and across the United States, Native Americans were forced to attend institutions like Goins School. Here, they were educated separately from other races. While the law required students in any school to receive the same standard of education, Native American schools were underfunded and lacked the resources that white schools had.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Rockingham County Public Library

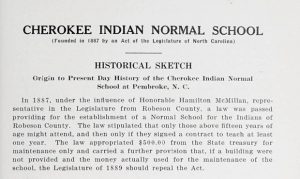

Catalogue of the Cherokee Indian Normal School

Pembroke, N.C. (Robeson County), 1938

In 1887, the Croatan Normal School was established in Robeson County, North Carolina after Native Americans in the area petitioned for a school. The school was later named Cherokee Indian Normal School. After desegregation, it eventually became the University of North Carolina at Pembroke. This 1938 course catalog from the Cherokee Indian Normal School provides a brief description of the institution’s history and its purpose to educate Native Americans to become teachers.

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Pembroke

"Native Americans try to educate, enlighten," The Guilfordian

Greensboro, N.C. (Guilford County), 1993

At Guilford College’s student-run Native American Club, members seek to expose other students to Native American history and culture. According to this 1993 article from The Guilfordian, the club taught students about Cherokee history, led discussions on Native American children forced to attend boarding schools, and demonstrated traditional Native American dances and sports. The club also acts as a support group for its Native American members. One individual stated that it is a way “…to express concerns, form a bond, and have somebody there who understands our background.”

Contributed to DigitalNC by Guilford College

"Working To Preserve Cherokee Language," The Smoky Mountain Times

Bryson City, N.C. (Swain County), 1980

This article from The Smoky Mountain Times examines an effort to preserve Cherokee language through class instruction at Western Carolina University (WCU). The endeavor was led by Cherokee storyteller Robert Bushyhead. Like many other Native American children in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Bushyhead was forced to attend a boarding school. These schools banned Native students from participating in their cultural practices and punished them for speaking Indigenous languages, like Cherokee.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Fontana Regional Library, Western Carolina University, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

"Sixteenth Annual American Indian Heritage Celebration" The Carolina Times

Durham, N.C. (Durham County), 2011

This article from The Carolina Times promotes the American Indian Heritage Celebration, held in Raleigh every November and dedicated to “…help celebrate, educate and tell the story of American Indians in our state.” The events for the 2011 celebration included music and dance performances, discussions with Native artisans, hands-on crafting opportunities, and exhibits.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Durham County Library, State Archives of North Carolina, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Coharie Tribal Center

Clinton, N.C. (Sampson County), 1970

This photograph depicts the Coharie Tribal Center in Clinton, North Carolina. Like other Native American groups, the Coharie were racially segregated in schools during the early to mid 20th century. While the Coharie had a right to receive an education, there were few high school classes in the area. In 1941, an act passed by the North Carolina legislature allowed funding for the construction of the East Carolina Indian School, a high school that would go on to educate Coharie tribal members and other Native Americans in nearby counties. Since the school’s closure in 1965, the building has served as the Coharie Tribal Center. The center annually hosts the Coharie’s powwow event, where tribal members can come together to celebrate and strengthen their heritage.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Sampson Community College

"The Unbroken Circle," Feeding the Ancient Fires

North Carolina, 1999

Feeding the Ancient Fires is a collection of writings and poetry from Native Americans living in North Carolina. Writers from five of the eight North Carolina tribes are represented in the book, alongside writers from other tribes in different areas. The writings are grouped into four overarching themes, including “The American Indian Woman,” “The Circle of Life,” “Ritual Power and Cultural Survival,” and “The Power of Change from Contact.” The piece shown here comes from Ladonna E. Evans of the Haliwa-Saponi tribe, who writes about legacy and the connections between Native ancestors and their descendants.

Contributed to DigitalNC by North Carolina Humanities Council

Background

Native Americans have populated the area that now makes up North Carolina since the end of the last Ice Age, during the Pleistocene era (about 12,000 years ago). Contact with European colonists began in the early 1600s, which led to the settler-colonialism and westward expansion of the 18th and 19th centuries. The 20th century was also a time of oppression and change for Indigenous peoples in North Carolina. While certain legislation, policies, and media representations from 1900 to the present have affected and even harmed Native Americans, Indigenous groups have made efforts to protect their cultures and communities.

Today, North Carolina is home to eight state-recognized tribes, which include the Coharie tribe, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the Haliwa-Saponi tribe, the Lumbee tribe, the Meherrin Indian tribe, the Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation, the Sappony, and the Waccamaw Siouan tribe. Of these eight groups, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians is the only one to have received full federal recognition. While the Lumbee tribe is the largest in North Carolina, it has only been partially recognized by the federal government in the Lumbee Act of 1956. The Lumbee tribe has since worked to obtain full recognition by introducing bills, creating petitions, and forming committees in hopes of receiving the same benefits and funding as fully recognized tribes.

Although federal recognition of tribes has been a key part of Native American legislation, other types of legislation have also made significant changes. In 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act granted citizenship to all Native Americans born within the United States. However, the act failed to properly secure voting rights for Indigenous communities; many states continued to deny Native Americans their right to vote. Ten years later, the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act passed. The act ended the allotment of tribal lands, put funds toward Native American education, and encouraged tribes to establish governments and constitutions modeled after that of the United States. The act has received mixed reactions, as some argue that it strengthened tribal communities, while others say the act failed to address the different needs of tribes. In 1972, the General Assembly created the North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs. The Commission provided Native American communities with an opportunity to work with the state to address issues, advance social and economic development, and advocate for their communities’ right to engage in their cultural and religious practices.

Education was another significant source of change for Native Americans in the 20th century. Beginning in the mid-1800s, Indigenous children in North Carolina and across the country were forced to attend segregated boarding schools led by white instructors. Students were banned from participating in their cultural practices and punished for speaking Native American languages, like Cherokee. One institution, the Croatan Normal School, was established in 1887 to train Native Americans to become public school teachers. After desegregation, the school expanded its mission and curriculum. It eventually became the University of North Carolina at Pembroke in 1996.

Representations of Native Americans in the media have also affected the Indigenous communities of North Carolina. While several popular outdoor plays portray Native American characters, their representations differ. Some of these outdoor dramas, like Unto these Hills, have long casted Native actors to play Native American characters. A play called The Lost Colony, however, has a history of casting white actors in Native roles and using skin-darkening makeup. In recent years, The Lost Colony has acknowledged its racist practices. Its creators have worked to improve its depiction of Native American characters by casting Indigenous actors and placing Native Americans on the board that oversees the play.

The Native Americans of North Carolina have experienced significant changes and challenges from 1900 onward. Nevertheless, their communities have continuously worked to preserve their cultures and traditions. In 2006, Governor Michael Easley proclaimed November as American Indian Heritage Month. Easley marked it as a time to acknowledge and celebrate Native Americans across the state. Every November, Raleigh holds an American Indian Heritage Celebration, where visitors can learn about Indigenous culture through performances, exhibits, and demonstrations. Heritage preservation has also occurred on college campuses across North Carolina, with Indigenous students creating clubs to support Native students and teach others about Native American history, art, and culture. For tribes like the Cherokee, language has been a key part of protecting heritage. At Western Carolina University, Cherokee language courses have been taught to undergraduates since the 1980s. Institutions like the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University have also begun to teach classes on the Cherokee language.

Discussion Questions

Consider the two playbills from The Lost Colony outdoor drama, one from 1947 and the other from 2021. How does the older playbill portray Native Americans in its historical introduction? How does the portrayal differ from how the 2021 playbill describes the play’s Native characters and actors?

- What do these playbills tell you about perspectives on Native Americans?

- Do you think the 2021 playbill does a good job of supporting and portraying Native Americans? What considerations should the media take into account when portraying Native Americans characters and stories?

While there are eight Native American tribes in North Carolina, only one tribe, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, has received full federal recognition. Consider the differences in how tribes in North Carolina are recognized. How might the communities of the non-federally recognized tribes be affected by the lack of recognition?

- In what ways has the Lumbee tribe tried to gain recognition? How do you think the Lumbee specifically are affected by the lack of federal recognition?

The Native American boarding school system played a significant role in the forced assimilation of Indigenous people. Why was this system harmful to Native children and families? In what ways have boarding schools and assimilation had lasting effects on Native Americans today? Consider Indigenous practices, languages, and culture.

How has federal and state legislation in the 20th century onward impacted Native Americans in North Carolina? How has it affected their cultures and economies?

In what ways have Native Americans in North Carolina preserved and strengthened their cultures and communities during the 20th century to the present? What challenges have they faced that have impeded this endeavor?

For Teachers

These materials were compiled by Isabella Walker. Updated March 2025.

https://www.digitalnc.org/primary-source-sets/native-americans-in-north-carolina-1900-to-the-present/

This document was prepared for print on August 29, 2025.