Primary Source Set

The Eugenics Movement in North Carolina

Between 1929 and 1974, over 7,600 people were sterilized, or made unable to have children, in North Carolina. Sterilization was a key part of eugenics, a theory and movement that claimed it could improve humankind through selective breeding. Through sterilization, North Carolina restricted the fertility of individuals that were considered “undesirable.” Many were forced or coerced into sterilization. This primary source set uses newspaper articles, newspaper advertisements, and a bulletin to illustrate the effects of sterilization, eugenic ideas, and eugenic legislation in North Carolina.

Proceed with caution and care through these materials as the content may be disturbing or difficult to review. Many primary sources in this set use eugenicist ideas to support the discrimination of non-white people and people with mental illness or mental disability. Please read DigitalNC’s Harmful Content statement for further guidance.

Time Period

1912-2014

Grade Level

Undergraduate

Transcript

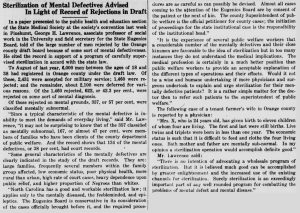

"Sterilization of Mental Defectives Advised In Light of Record of Rejections in Draft," The Chapel Hill Weekly

Before and during World War II, hundreds of thousands of North Carolina men were drafted to fight in the conflict. While many men were subject to the draft, some individuals were rejected due to various reasons, including “mental defectiveness.” This 1946 article from The Chapel Hill Weekly provides the statistics of draft rejections in Orange County. It then uses these statistics to argue for sterilizing “the mentally diseased, the feebleminded, and epileptics.”

Contributed to DigitalNC by University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Chapel Hill, N.C. (Orange County)

Background

First proposed by Sir Francis Galton in 1883, eugenics claims humankind can improve through selectively breeding for traits that are considered desirable or superior. Although eugenics is scientifically incorrect and unethical, the early to mid-twentieth century saw the eugenics movement gain widespread popularity across the United States, including North Carolina. From 1929 to the late 1970s, North Carolina upheld and validated the eugenics movement through legislation and public promotion of sterilization.

Sterilization procedures allowed North Carolina to restrict or eliminate the fertility of people who were considered “undesirable.” Some examples of “undesirable” people included individuals with mental disabilities. In the articles and advertisements in this set, these individuals are often referred to as “feebleminded” and “mentally defective.” Eugenics supporters believed that the children of such people could inherit their “inferior” traits, causing a “burden” on the parents, the public, and the state. By sterilizing people, they thought the burden could be alleviated. While sterilization was aimed at people with disabilities, the procedure was also used extensively on non-white people or people whose sexual or social behavior was considered “defective.” Selective sterilization groups like the Human Betterment League claimed that the procedure was done with the consent of the patient or their family. However, many individuals were forced or coerced into sterilization.

In 1929, the General Assembly passed a law that permitted the sterilization of individuals held in any charitable or penal institutions in North Carolina when the sterilization was determined to be the best course of action for the individual or for the public good. In 1933, the General Assembly established the North Carolina Eugenics Board. Made up of five state government members, the Eugenics Board was responsible for reviewing and approving all sterilization procedures in North Carolina. In 1937, Assembly members passed another act that permitted state hospitals to temporarily admit and sterilize people who had been approved for the procedure by the Eugenics Board. While sterilization and eugenics were normalized and embraced in North Carolina during the early to mid-20th century, the 1970s saw public criticism rise. After a name change from the Eugenics Board to the Eugenics Commission in 1973, the group was abolished by the General Assembly in 1977.

In 2002, Governor Michael Easley made an official declaration to victims of forced or coerced sterilization. He apologized for the role that the North Carolina government had played in supporting and promoting selective sterilization. Easley also established a Eugenics Study Committee. In 2003, he repealed legislation that still made sterilization legal in the state. In a report made by the Eugenics Study Committee, members stated their belief that North Carolina should provide financial compensation to victims. Representative Larry Womble, who was part of the committee, later introduced a bill to give a sum of money to those affected by forced sterilization. However, it was not until 2010, when the Office of Justice for Sterilization Victims was created, that a compensation plan was put in place. By 2014, eligible individuals who made a claim to the Office received $20,000 or more as payment. Some have called the program flawed, as many victims were thought to have died by the time it was created. Moreover, only individuals whose sterilizations were approved by the Eugenics Board could file a claim; others who were sterilized under a different authority’s mandate were not able to receive compensation from the Office.

Discussion Questions

Consider the first and second newspaper advertisement from the Human Betterment League. How do they describe the consequences of not sterilizing “feebleminded” and “mentally deficient” individuals? What tactics do they use to defend and justify sterilization procedures?

Many of the primary sources in this set are newspaper articles or advertisements that promote selective sterilization to the public. How did mass media–like newspapers–influence the North Carolina public’s perspective on eugenics and sterilization?

From the early to mid-twentieth century, selective sterilization was normalized and even encouraged in North Carolina. What factors contributed to the normalization and general support of sterilization?

While the North Carolina government eventually established a compensation initiative for forced sterilization victims in 2010 and began payments in 2014, many have pointed out the flaws in the initiative. What are some of the issues in the compensation program, and what could the North Carolina government have done to better support victims of forced sterilization? Is there anything North Carolina can do today?

Consider the viewpoints in The Carolina Times article, The North Carolina Catholic article, and The News-Journal article. What different perspectives do you notice in each piece? How does criticism of sterilization in The Carolina Times article differ from that in The North Carolina Catholic piece?

Take a look at the article from The Smithfield Herald, making sure to notice the ways in which “better babies” are described. How does the “Better Babies Health Contest” connect to other eugenicist concepts, like selective sterilization?

This primary source set was compiled by Isabella Walker.

Updated January 2025