Primary Source Set

Native Americans in North Carolina, 1900 to the Present

Today, North Carolina is home to over 130,000 Native Americans and eight state-recognized tribes. Native American communities have been severely impacted since the first instances of European colonization in the 1600s, but the 20th century brought particular kinds of legislation, policies, and media representations that have affected the Indigenous peoples of North Carolina. With materials dating between 1900 and the present, this primary source set uses photographs, maps, catalogs, newspaper articles, and pamphlets to illustrate the challenges faced by North Carolina Native Americans and the efforts made to preserve their cultures and communities.

Proceed with caution and care through these materials as the content may be disturbing or difficult to review. Some sources include racist portrayals of Native Americans or contain descriptions of violence and discrimination enacted upon Native Americans. Please read DigitalNC’s Harmful Content statement for further guidance.

Time Period

1920-2019

Grade Level

Undergraduate

Transcript

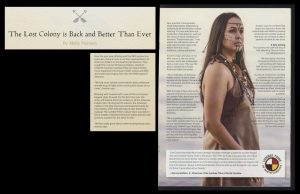

"The Lost Colony is Back and Better Than Ever," The Lost Colony Souvenir Program

Since 1937, an outdoor play called The Lost Colony has been put on in Manteo, North Carolina almost every summer night. Based on the failed English attempt to colonize Roanoke Island, the play has a history of using skin-darkening makeup and casting non-Indigenous actors to play Native American characters. This section of the The Lost Colony playbill from the 2021 season acknowledges the play’s former racist practices and discusses how the play has changed to better represent its Native American characters.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Roanoke Island Historical Association

Manteo, N.C. (Dare County)

Background

Native Americans have populated the area that now makes up North Carolina since the end of the last Ice Age, during the Pleistocene era (about 12,000 years ago). Contact with European colonists began in the early 1600s, which led to the settler-colonialism and westward expansion of the 18th and 19th centuries. The 20th century was also a time of oppression and change for Indigenous peoples in North Carolina. While certain legislation, policies, and media representations from 1900 to the present have affected and even harmed Native Americans, Indigenous groups have made efforts to protect their cultures and communities.

Today, North Carolina is home to eight state-recognized tribes, which include the Coharie tribe, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, the Haliwa-Saponi tribe, the Lumbee tribe, the Meherrin Indian tribe, the Occaneechi Band of the Saponi Nation, the Sappony, and the Waccamaw Siouan tribe. Of these eight groups, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians is the only one to have received full federal recognition. While the Lumbee tribe is the largest in North Carolina, it has only been partially recognized by the federal government in the Lumbee Act of 1956. The Lumbee tribe has since worked to obtain full recognition by introducing bills, creating petitions, and forming committees in hopes of receiving the same benefits and funding as fully recognized tribes.

Although federal recognition of tribes has been a key part of Native American legislation, other types of legislation have also made significant changes. In 1924, the Indian Citizenship Act granted citizenship to all Native Americans born within the United States. However, the act failed to properly secure voting rights for Indigenous communities; many states continued to deny Native Americans their right to vote. Ten years later, the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act passed. The act ended the allotment of tribal lands, put funds toward Native American education, and encouraged tribes to establish governments and constitutions modeled after that of the United States. The act has received mixed reactions, as some argue that it strengthened tribal communities, while others say the act failed to address the different needs of tribes. In 1972, the General Assembly created the North Carolina Commission of Indian Affairs. The Commission provided Native American communities with an opportunity to work with the state to address issues, advance social and economic development, and advocate for their communities’ right to engage in their cultural and religious practices.

Education was another significant source of change for Native Americans in the 20th century. Beginning in the mid-1800s, Indigenous children in North Carolina and across the country were forced to attend segregated boarding schools led by white instructors. Students were banned from participating in their cultural practices and punished for speaking Native American languages, like Cherokee. One institution, the Croatan Normal School, was established in 1887 to train Native Americans to become public school teachers. After desegregation, the school expanded its mission and curriculum. It eventually became the University of North Carolina at Pembroke in 1996.

Representations of Native Americans in the media have also affected the Indigenous communities of North Carolina. While several popular outdoor plays portray Native American characters, their representations differ. Some of these outdoor dramas, like Unto these Hills, have long casted Native actors to play Native American characters. A play called The Lost Colony, however, has a history of casting white actors in Native roles and using skin-darkening makeup. In recent years, The Lost Colony has acknowledged its racist practices. Its creators have worked to improve its depiction of Native American characters by casting Indigenous actors and placing Native Americans on the board that oversees the play.

The Native Americans of North Carolina have experienced significant changes and challenges from 1900 onward. Nevertheless, their communities have continuously worked to preserve their cultures and traditions. In 2006, Governor Michael Easley proclaimed November as American Indian Heritage Month. Easley marked it as a time to acknowledge and celebrate Native Americans across the state. Every November, Raleigh holds an American Indian Heritage Celebration, where visitors can learn about Indigenous culture through performances, exhibits, and demonstrations. Heritage preservation has also occurred on college campuses across North Carolina, with Indigenous students creating clubs to support Native students and teach others about Native American history, art, and culture. For tribes like the Cherokee, language has been a key part of protecting heritage. At Western Carolina University, Cherokee language courses have been taught to undergraduates since the 1980s. Institutions like the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Duke University have also begun to teach classes on the Cherokee language.

Discussion Questions

Consider the two playbills from The Lost Colony outdoor drama, one from 1947 and the other from 2021. How does the older playbill portray Native Americans in its historical introduction? How does the portrayal differ from how the 2021 playbill describes the play’s Native characters and actors?

- What do these playbills tell you about perspectives on Native Americans?

- Do you think the 2021 playbill does a good job of supporting and portraying Native Americans? What considerations should the media take into account when portraying Native Americans characters and stories?

While there are eight Native American tribes in North Carolina, only one tribe, the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians, has received full federal recognition. Consider the differences in how tribes in North Carolina are recognized. How might the communities of the non-federally recognized tribes be affected by the lack of recognition?

- In what ways has the Lumbee tribe tried to gain recognition? How do you think the Lumbee specifically are affected by the lack of federal recognition?

The Native American boarding school system played a significant role in the forced assimilation of Indigenous people. Why was this system harmful to Native children and families? In what ways have boarding schools and assimilation had lasting effects on Native Americans today? Consider Indigenous practices, languages, and culture.

How has federal and state legislation in the 20th century onward impacted Native Americans in North Carolina? How has it affected their cultures and economies?

In what ways have Native Americans in North Carolina preserved and strengthened their cultures and communities during the 20th century to the present? What challenges have they faced that have impeded this endeavor?

For Teachers

This primary source set was compiled by Isabella Walker.

Updated January 2025