Primary Source Set

Racial Integration in K-12 Schools

In the mid-20th century, the Supreme Court ruled that schools were no longer able to segregate students by race. This collection uses high school yearbooks, newspaper articles, photographs, video and oral history to illustrate how education changed between the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling and the mid-1970s, when North Carolina finally met the requirements set by that case.

Proceed with caution and care through these materials as the content may be disturbing or difficult to review. Please read DigitalNC’s Harmful Content statement for further guidance.

Time Period

1950s to 1970s

Grade Level

7 – 12

Transcript

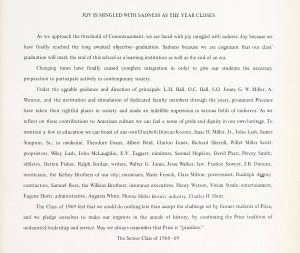

"Joy Is Mingled with Sadness as the Year Closes" in The Pricean [1969], Price High School

This letter from the Price High School class of 1969 reflects on the feelings of students as the school closes due to integration. Price High School was an all-Black high school in Salisbury, N.C.

Contributed to DigitalNC by Rowan Public Library

Salisbury, N.C. (Rowan County)

Background

In the early and mid-20th century, students in North Carolina attended schools based on their race. Despite segregationists’ “separate but equal” mantra, schools for white children were often better-resourced, with more money for buildings and school supplies. While schools for Black children usually received less money for textbooks, staff salaries, and facilities, they were still vibrant and close-knit communities. Students identifying as other races, including Native American students, were sometimes educated at Black schools and sometimes able to create schools for themselves, including the High Plains School in Person County. In 1954, the Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that schools were no longer able to segregate students by race. However, it took North Carolina 17 years before our state’s schools met the conditions of the Brown v. Board ruling.

Between 1954-1972, lawmakers and community groups debated the best ways to racially integrate schools. Many white families opposed integration and protested by staying home from school or moving to newly-formed private schools. Meanwhile, many Black families worried about leaving the schools they knew, many of which were dissolved as part of integration. One of the largest debates about integration was about busing, a method where students would be bussed across their districts to create schools with racially-balanced student bodies. This method led to the Supreme Court case Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education (1971), which confirmed busing as an appropriate strategy and served as the basis for cases around the country.

While the legacy of school integration is complex, this period affected the educational paths of many North Carolinians. One way to more fully understand how students’ lives were changed is to look at examples from yearbooks, photographs, and newspaper articles from this time. In particular, Black community newspapers and yearbooks from Black high schools offer several viewpoints about transitioning to majority-white schools.

Discussion Questions

When did N.C. public schools become racially integrated? Was it in 1954 after Brown v. Board of Education? Was it in 1972, when the state finally met the requirements of the Brown v. Board ruling? Was it sometime in between or after?

Take a look at Gohisca [1971] from Goldsboro High School and Charger [1971] from Wayne Country Day School. What differences do you see? How do the attitudes of students differ? What do these differences tell you about the motivations of private schools during this time period?

Consider the two articles from The Carolinian (Raleigh, N.C.) and the two yearbook excerpts from The Panther [1968] and The Pricean [1969]. What are some of the contrasting feelings coming from community members, school staff, and students? Why do you think each of these authors has these feelings?

In his interview, Tony Brown says that he was glad he stayed at his majority Black school, saying, “We had a lot of very, very caring teachers and it was a smaller environment, nurturing environment.” Given the reactions of some white students and families toward integration, what do you think about Brown’s stance?

School integration in the South sometimes began with one or a few Black students moving to an all-white school (like in the case of Gwendolyn Bailey). Take a moment to imagine yourself in their position. Would you go through with it? Why or why not?

Take a look at The Hilltopper [1963]. This is a yearbook from the first year that Native American students had to attend Bethel Hill High School (previously an all-white school). What surprises you about this yearbook? What do you think this school year was like for students?

If you were a N.C. lawmaker in 1954, what plans would you propose to integrate schools? Would you move all students into the white schools for their resources? Would you use buses to transport students and make the schools racially representative? Would you allow families to choose which schools they wanted to attend?

This primary source set was compiled by Sophie Hollis.

Updated January 2025