DigitalNC is excited to introduce a new primary source teaching set on urban development and renewal in North Carolina. While urban renewal impacted communities across the United States and North Carolina, this set focuses on how two neighborhoods in Durham and Raleigh experienced loss and displacement as a result of redevelopment. Additionally, this set discusses other community “revitalization” trends in North Carolina, such as the Finer Carolina contest of the 1950s.

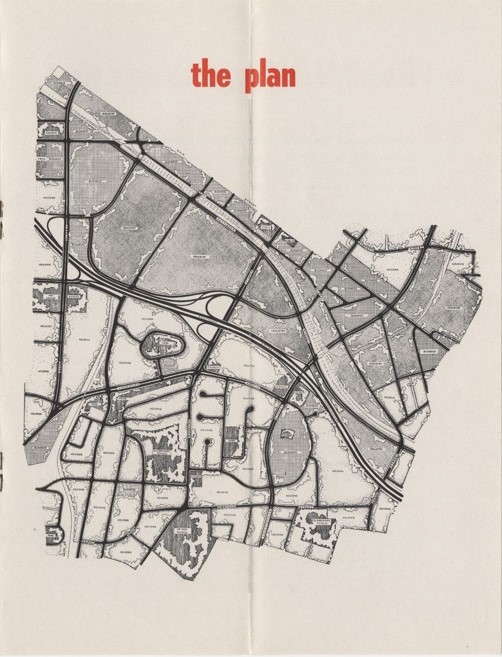

Like our other primary source sets, this urban renewal set is made up of various written (newspaper articles, pamphlets) and visual (maps, scrapbooks, government records) materials. Other sections include discussion questions, outside resources, background information, and a timeline, as well as context statements for each item. Here’s a closer look at the Urban Development and Renewal primary source set:

Urban Development and Renewal

Time period: 1954-1974

The passing of the Housing Act in 1949 allowed the federal government to provide funding for cities across the United States to seize and demolish “blighted” or “slum” neighborhoods. “Urban renewal” was the term used to describe this process, as these programs promised to construct better housing, invite in new industries, and generally improve urban areas. Redevelopment programs often targeted neighborhoods with a high percentage of Black residents, many of whom were displaced as a result of urban renewal. Despite the positive assurances made to these communities, many areas never received the promises made by their cities’ redevelopment commissions. Low-income housing, revitalized business, and most other plans made never materialized, even many years after urban renewal began.

Despite the often harmful consequences of these programs, urban renewal generated a broader trend of redevelopment in North Carolina. In the 1950s, the Carolina Power and Light Company created the Finer Carolina contest, in which cities and towns across the state competed for cash awards by “beautifying” and making improvements to their communities. Although Finer Carolina programs did improve infrastructure and attract new industry in North Carolina towns, many contest scrapbooks show that historic buildings were destroyed in the process due to their “shabby” or “unsightly” appearances.

Teacher, students, researchers, and anyone interested in learning more about urban renewal in North Carolina can find the primary source set on our resources page. If you would like to give us feedback on the sets, please contact us here.