- This post shares information about scanners and content management or online platforms used by some North Carolina cultural heritage organizations.

- The lists are current as of this post and they are not exhaustive.

- For more information, get in touch with us.

People frequently ask us to recommend digitization equipment as well as content management systems* or ways to display their files online. To help connect more people to their peers, we sent our partners a survey asking them the following:

- List the make and model of any equipment you have that scans print materials, photographs, slides, and/or negatives.

- What local or remotely hosted software does your organization use to keep track of and/or share your digital images?

Thanks to the 45 institutions who responded, we now have a great list on hand. If you contact us we can connect you directly with those who said they’d be happy to share experiences and information.

Keep reading for lists of all of the equipment and software mentioned listed in alphabetical order. If you work in a cultural heritage organization in NC and don’t see your digitization equipment and/or system mentioned below, leave a comment and we will add it.

*A content management system is software that will store and organize files, usually with functionality that helps people make use of the files like search, online display, etc.

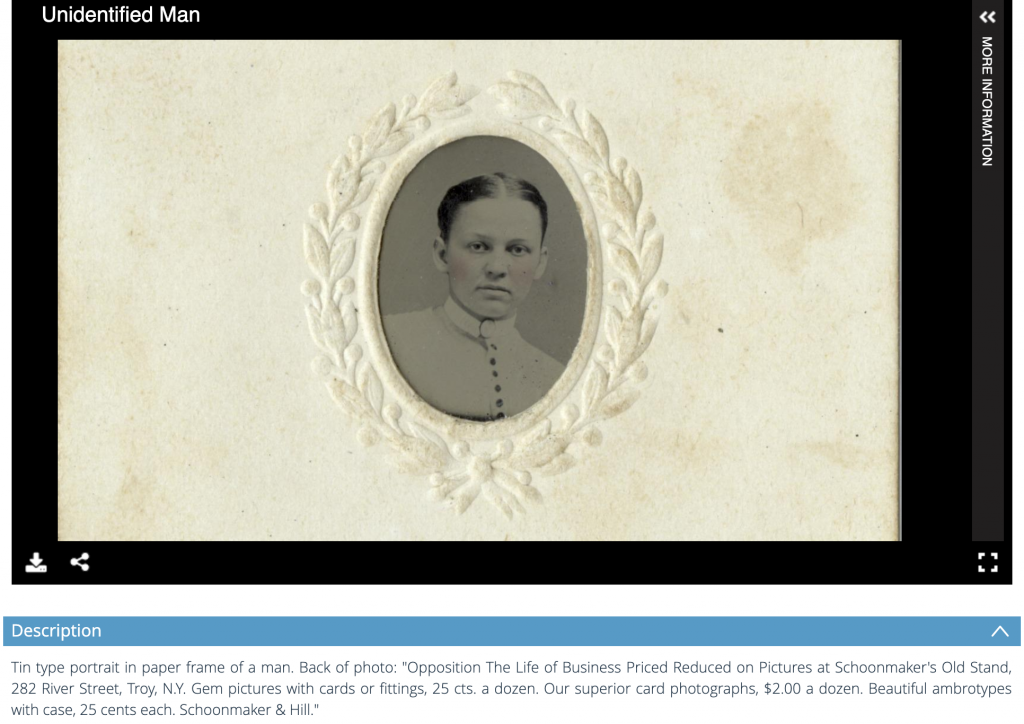

Here’s the list of platforms mentioned:

Content Management Systems / Online Platforms

- Alma Digital/ Primo VE

- CONTENTdm

- Cumulus

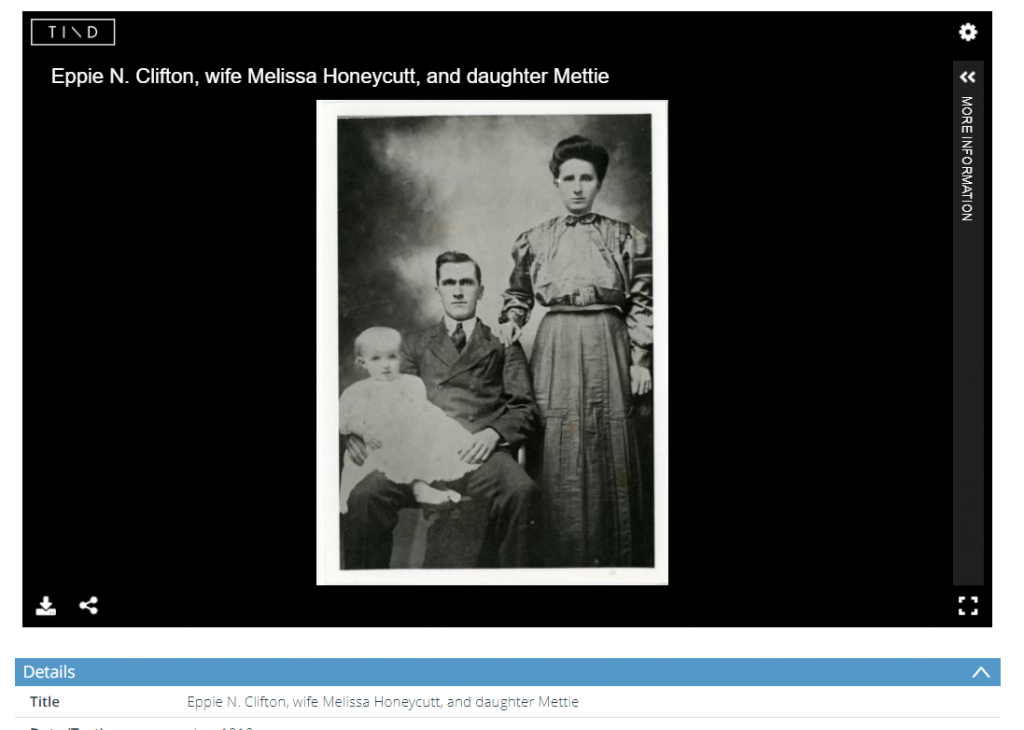

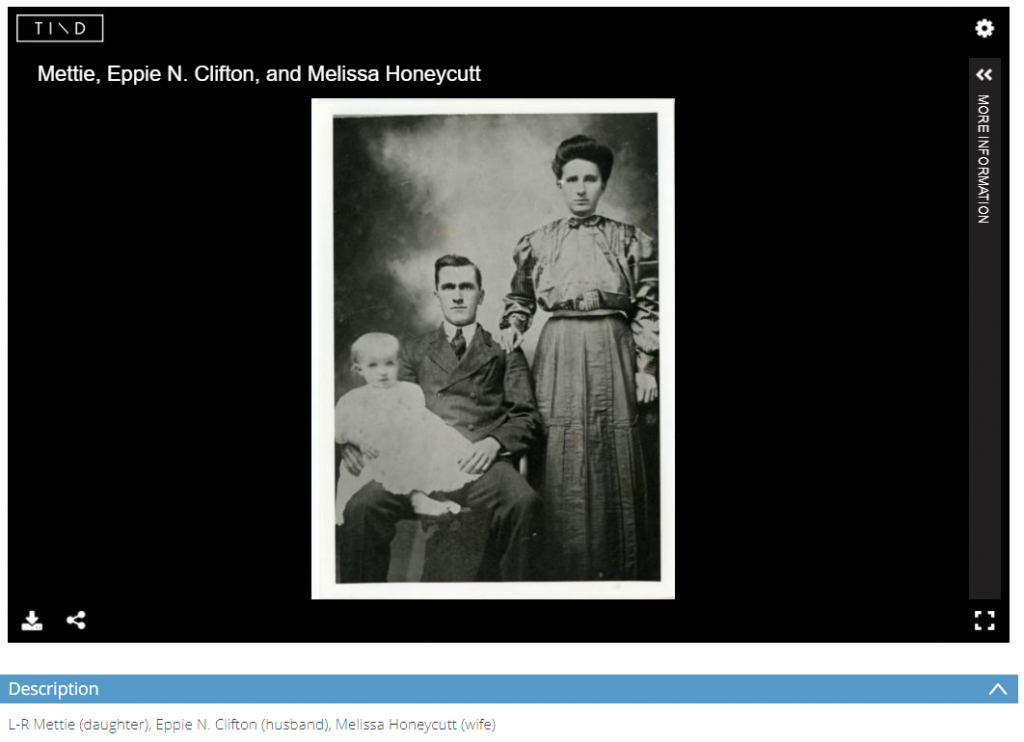

- DigitalNC (which uses TIND, WordPress, and Open ONI)

- DSpace**

- Drupal

- Ex Libris Alma Digital

- Fedora + Hyrax**

- Flickr

- Internet Archive

- Islandora

- JSTOR Forum

- KeepThinking Qi**

- Laserfishe

- LibGuides

- Omeka

- Pass It Down

- Past Perfect

- PTFS Knowvation

- Quartex**

- Re:discovery Proficio

- WordPress

** Not represented in the survey responses but we know folks who use these.

Comments: Some of these are hosted by vendors; others are hosted by the organization. There are also sites listed here that might not be considered content management systems but that organizations use for online sharing. This list does not include social media sites where files might be shared, like Facebook, Instagram, Twitter. It also doesn’t get into details for those who have built their own systems (typically very well-resourced institutions). If you’d like some more guidance about choosing, check out this post: What Should You Do With Your Scanned Photos?

Here’s the list of equipment mentioned:

Flatbed Scanners

- Epson 10000XL, 11000XL, 12000XL

- Epson DS-50000

- Epson Perfection V19, V39, V370, V550

- Epson Perfection V600, V700, V800

- HP Scanjet G4050

- HP ScanJetPro 2500 f1

Large Format Sheet-fed Scanners

- HP DesignJet T2500

Overhead Scanners / Book Scanners

- Bookeye 3, 5

- Czur ET18 Pro

- Fujitsu ScanSnap 600

- ST600 Book Scanner

- Zeutschel OS 12000 A1, Q1

Overhead Camera Systems

- Phase One iXH 100MP camera + digital back

- Sony A7R IV camera with mount

Negative and Slide Scanners

- Hasselblad Flextight X5

- Nikon Super CoolScan 9000 ED

- PowerSlide 5000

- ZONOZ FS-3 22MP All-in-1 Film & Slide Converter Scanner w/Speed-Load Adapters for 35mm

Microfilm Scanners

- ST ViewScan 3, 4

Multi-Function Devices

- Epson-WF-3540

- Hewlett Packard Color LaserJet M476 copier with scanner

- HP Officejet Pro X576dw

- Konica Minolta bizhub 227 copier/scanner

- Kyocera Taskalfa 4053ci

- Savin IM 2500, MP 2004ex

- Sharp MX-4071, MX-C304W

- TASKalfa 3051ci

- Xerox Documate 3220 desktop scanner

- Xerox Workcentre 6655i, 7535

Comments: Some of these are staff use, some are available to the public, and some serve both groups. If you’re interested in what we use, take a look at this page: Scanning and Digitization Equipment

![Screenshot of an edited Sonix transcription. The text reads Mary Lewis Deans: Tell me how you heard about it. Kermit Paris: I was working in the bakery in [?]. I don't know, just before Carolina Theater opened up [?], once before I used to live right there. We was on the railroad tracks when I heard it. And, sure enough, I reckon ten or fifteen minutes after then, some artillery had come down the train, I remember that, going north. Artillery and some tanks was going down. They had guards on the flat cars, I'd seen some soldiers on the flat cars at that time. I do remember that.](https://www.digitalnc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/sonix_screenshot_2-1.jpg)