Like “Jeopardy!,” I want to tell you the answer before I get to the question.

Following a newspaper digitization and markup standard helps us plan for the future and makes it easier for us to work with vendors, open-source software, and other libraries and archives.

I say this up front, because when we explain how we digitize and share newspapers the frequent response is to ask why we do it the way we do. I think this is because our process is more labor intensive than people expect. It’s definitely not the only way, but we’re committed to this path for right now because it accommodates multiple formats (microfilm, print, born-digital), fits our current digitization capacity, and results in a system we think is flexible and extensible.

That standard I mentioned above comes out of the Library of Congress’ National Digital Newspaper Program (NDNP). All of our newspaper work is NDNP compliant, which means we follow that project’s recommendations for how to structure files, the type of metadata to assign to those files, and also the markup language that tells the computer where words are situated on each page (very helpful for full-text search).

I’ll give you a broad outline of our workflow and the tools we use. However, if you want more specific technical details, head over to our account on GitHub.

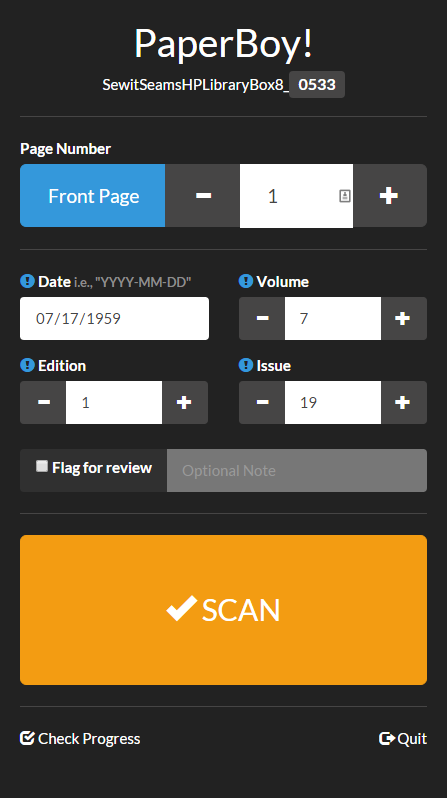

Screenshot of PaperBoy!

Let’s say one of our partners is interested in having us digitize a print newspaper. We’ll start by scanning each page separately on whichever machine works for the paper’s size. Because the NDNP standard requires page-level metadata, we’ve created a lightweight piece of software that helps us take care of some of that while we scan. Affectionately dubbed “PaperBoy,” this program allows the scanning technician to track page number, date, volume, issue, and edition for each shot. While it slows down scanning a little bit, it speeds up post-processing metadata work quite a lot.

Once the scanning’s complete, we process the files to create derivatives that serve different needs. We use ABBYY Recognition Server to get those multiple formats:

- a JPEG2000 image that’s excellent quality yet small in file size

- an XML file that includes computer-recognized text from the image along with coordinates that indicate the location of each word on that image

- a .pdf file that includes both the image and searchable text.

Now that we have the derivatives, we begin filling out a spreadsheet with page-level metadata. We first add the metadata created using Paperboy and then we run through the scans page by page, correcting any mistakes found in the Paperboy output and adding additional metadata. This also helps us quality control the scans and gives us a chance to find skipped pages.

How much metadata do we do? You can download a sample batch spreadsheet from GitHub, if you’re interested in the specifics, but it includes the PaperBoy output as well as fields like Title, our name (Digital Heritage Center) as batch-creators, and information about the print paper’s physical location. A lot of those fields stay the same across numerous scans or can be programmatically populated with a spreadsheet formula, to help make things go faster.

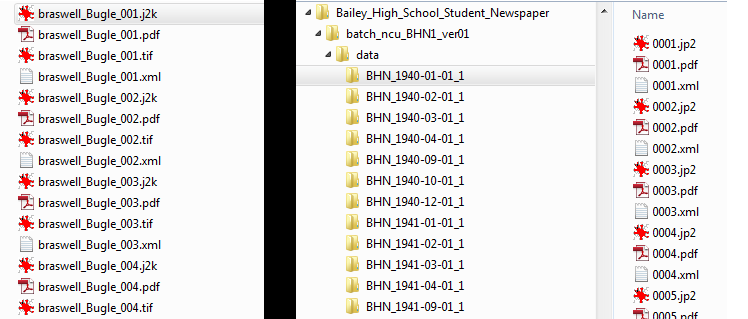

Once we have the spreadsheet and scans complete, scripts developed by our programmer (also available on GitHub) use those spreadsheets to figure out how to rearrange the files and metadata into packages structured just the way the NDNP standard likes them. The script breaks out each newspaper issue’s files into their own file folder, renaming and reorganizing the pages (if needed). The script also creates issue-level XML files, which tag along inside each folder. These XML files describe the issue and its relation to the batch, and include some administrative metadata about who created the files, etc.

Newspaper files before processing (left) and after (right).

The final steps are to load our NDNP-compliant batches into the software we use to present it online, and to quality control the metadata and scans.

If you think about it, newspapers have a helpfully consistent structure: date-driven volumes, issues, and editions. But there isn’t much else in the digital library world quite like them, so more common content management systems can leave something to be desired for both searching and viewing newspapers. Because of this, and because there’s just so MUCH newspaper content, we use a standalone system for our newspapers: the Library of Congress’ open source newspaper viewer, ChronAm. It’s named as such because it also happens to be the one used for the NDNP’s online presence: the Chronicling America website.

While not perfect, this viewer does really well exploiting newspaper structure. It also allows you to zoom in and out while you skim and read, and it highlights your search terms (courtesy of those XML files created by ABBYY). Try it out on the North Carolina Newspapers portion of our site.

“Can’t you just scan the newspaper and put it online as a bunch of TIFs or JPGs?” Sure. That happens. But that brings me back around to the why question. We love newspapers (most of the time) and love making it as easy and intuitive to use them as we can. We think it’s important to exploit their newspapery-ness, because that’s how users think of and search them.

We also believe that standards like the one from NDNP are kind of like the rules of the road. While off-roading can be fun, driving en masse enables us to be interoperable and sustainable. Standards mean we have a baseline of shared understanding that gives us a boost when we decide we want to drive somewhere together.

This post’s bird’s eye view (perhaps a low-flying bird) doesn’t include more specific questions you may be asking (“What resolution do you use when you scan?” “You didn’t explain METS–ALTO!”) I also just tackled our print newspaper procedure, because it’s the most labor intensive. When we work with digitized microfilm and born-digital papers the procedure is truncated but similar.

I hope this post as well as part 1 and part 2 of this series give you a sense of what’s involved in our newspaper digitization process and why we do it the way we do. As always, we’re happy to talk more. Just drop us a line.

The North Carolina Digital Heritage Center is launching a pilot project to help preserve and improve access to historic films and videos in North Carolina’s libraries, archives, and museums. Working with its partners around the state, the Center will select a small number of films and videos, which will then be sent to a vendor to be digitized. The resulting digital files will be published online at DigitalNC.org where they will be made freely available to all users. The original films or videos will be returned to the institutions that contributed them.

The North Carolina Digital Heritage Center is launching a pilot project to help preserve and improve access to historic films and videos in North Carolina’s libraries, archives, and museums. Working with its partners around the state, the Center will select a small number of films and videos, which will then be sent to a vendor to be digitized. The resulting digital files will be published online at DigitalNC.org where they will be made freely available to all users. The original films or videos will be returned to the institutions that contributed them.