Viewing search results for "State Archives of North Carolina"

View All Posts

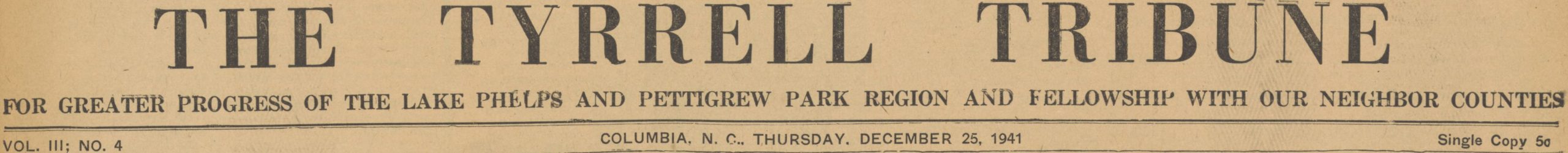

Thanks to the staff at the Outer Banks History Center, we now have a complete run of the 1941 Tyrrell Tribune available online. These papers were scanned at our office in Elizabeth City.

Thanks to the staff at the Outer Banks History Center, we now have a complete run of the 1941 Tyrrell Tribune available online. These papers were scanned at our office in Elizabeth City.

Search results showing the 1941 front pages let you easily see which issues are from microfilm and which from print.

North Carolina has an astounding amount of newspaper on microfilm thanks to efforts of the State Archives, newspaper publishers, local libraries, and other cultural heritage institutions. One thing we really love to do is use DigitalNC to join together microfilmed issues with print issues that have never been microfilmed. The Tyrrell Tribune is one of these cases.

For us, digitizing from microfilm is more cost-effective than digitizing from print. In addition, many papers that were microfilmed were disposed of when organizations were unable to afford storage and care. Microfilmed copies may be the only versions still available. However, there are cases where print issues held by our partners fill in for what was never microfilmed and the 1941 Tyrrell Tribune is a great example.

Published out of Columbia, N.C., the Tribune covers news about local government, coastal industry, agriculture, and events. You can see all of the issues that we have available from the Tribune here. All items we’ve scanned for the Outer Banks History Center are available through their contributor page. Everything we have about Tyrrell County can be found on the Tyrrell County page.

Another newspaper title from the eastern part of our state has been added to our digital collections thanks to our partner, the Outer Banks History Center. These issues of The Seashore News were published for the Nags Head, Kill Devil Hills, and Kitty Hawk beach communities in 1939.

One article from the June 8, 1939 issue describes a different beach scene than many of us are used to today.

“Dare County is being reborn,” it begins. “Where only a year or two ago the eye was greeted with vast stretches of bare sand and course beach grass, upon which herds of stunted cattle eked out a miserable existance [sic], today is springing to life lush vegetation, acres of wild flowers and trees and flowering shrubs of a hundred varieties.”

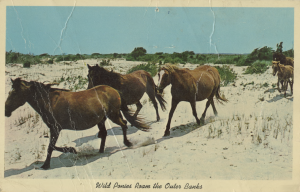

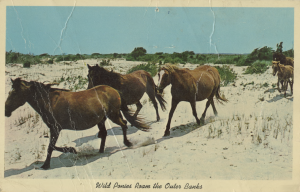

The article goes on to describe how the “Stock Law” passed in 1937 by the State Legislature helped eliminate the cattle, wild horses, and “scuttling flocks of mangy sheep” from the beaches. The author also claims that the beaches were a “veritable paradise of verdure” when colonists first arrived and that it was due to the livestock that the beaches became “a territory that was fast taking on the arid aspects of a desert.”

Whether the introduction of vegetation to the area would be considered “conservation” by today’s standards isn’t totally clear, though the NC Wildlife Resources Commission doesn’t exactly describe costal habitats as a “‘delicate garden abounding with all kinds of odiferous flowers.'”

You can see all issues of The Seashore News here, and you can browse all of our digital newspapers by location, type, and date in our North Carolina Newspapers collection. To learn more about the Outer Banks History Center, you can visit their partner page and their website.

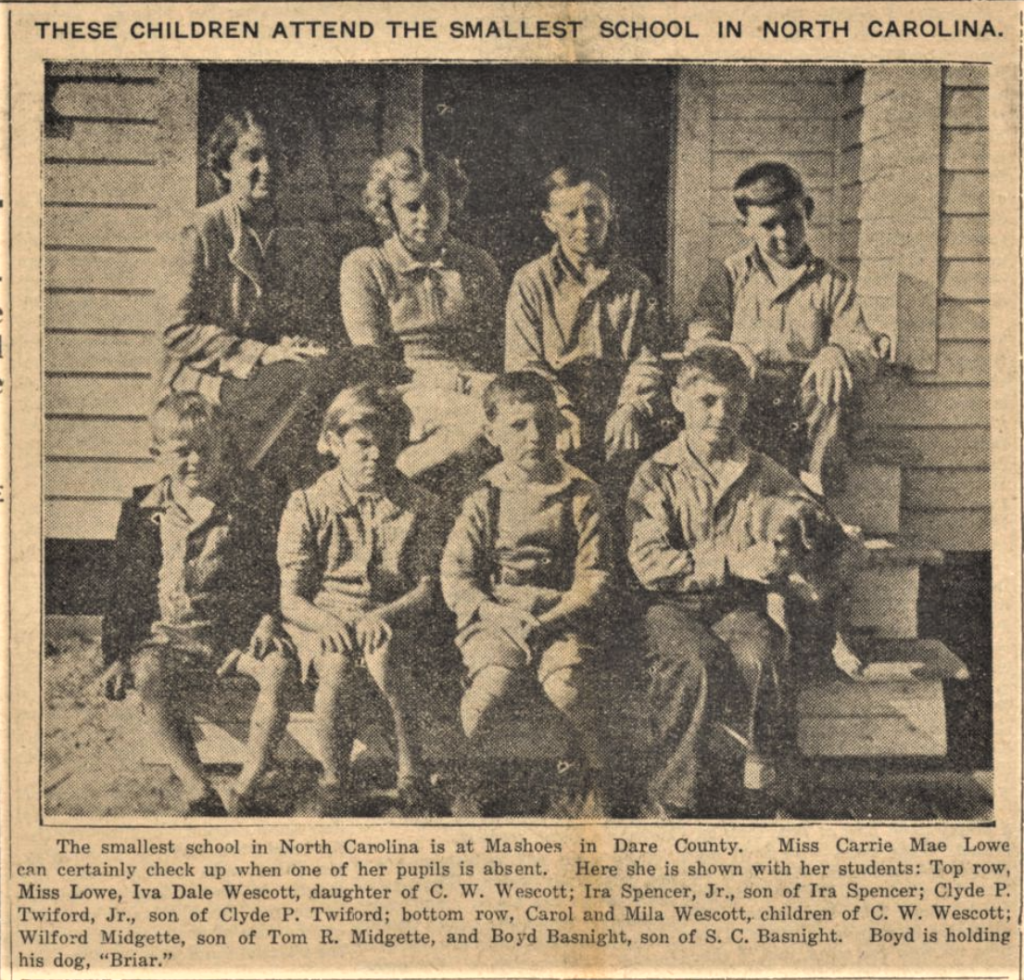

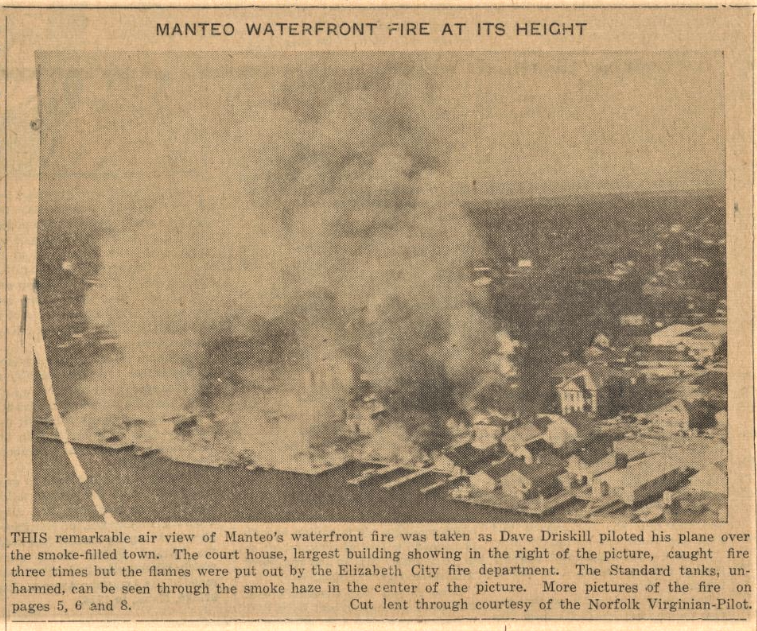

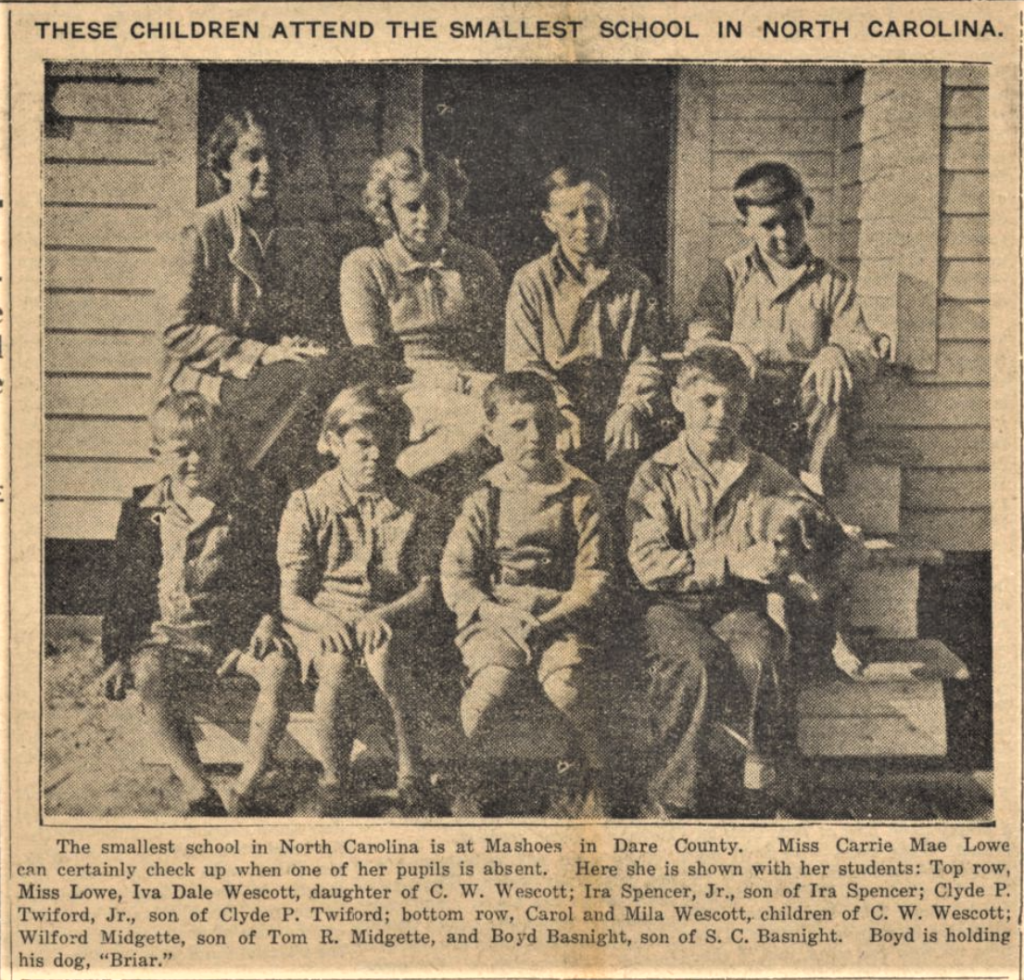

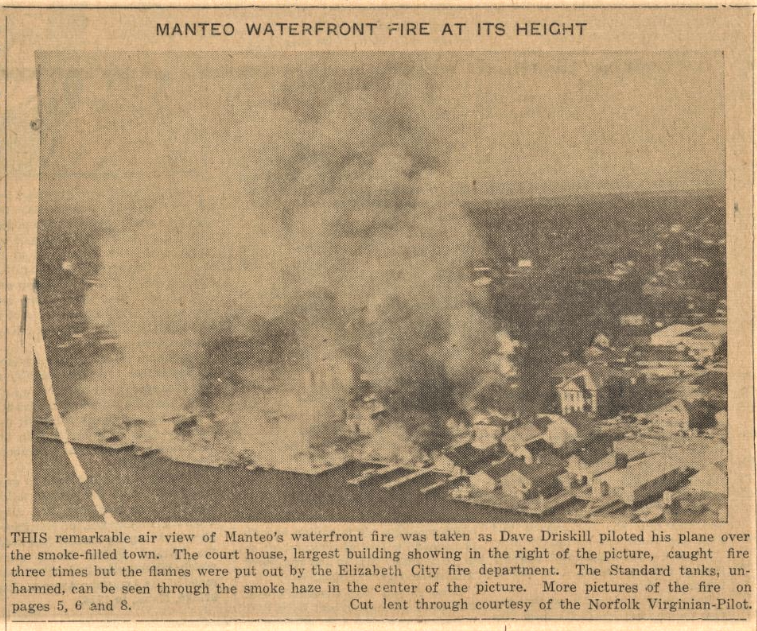

Thanks to our partner, The Outer Banks History Center, we now have every issue of The Dare County Times from 1935-1945 up on DigitalNC! In these papers we have stories about the smallest school in North Carolina (only seven students!), the 100th performance of Paul Green’s The Lost Colony, and the fire that devastated much of Manteo on September 11th, 1939.

The Manteo fire broke out in the early hours of that September morning and destroyed 21 buildings in just three hours. Since the town had limited supplies to fight the fire, trucks from neighboring communities had to be called in to help contain the flames and one even came down from Norfolk, Virginia to offer aid. Miraculously, not a single person was injured amidst the chaos.

If you would like to see the rest of the available issues of The Dare County Times, you can find them here. You can also browse our entire collection of North Carolina newspapers and visit our contributing partners page.

From the 1950-1976 scrapbook

The reverse side of the postcard

Our latest batch of materials from the Wayne County Public Library includes some seriously cool scrapbooks that document almost a century of the library’s history. Ranging from 1910 to the 1990s, these seven scrapbooks contain detailed minutes, photographs, newspaper clippings, event paraphernalia and other ephemera.

One of the most exciting sections is the collection of letters from North Carolina authors—who also happen to be mostly women—in the 1950-1976 scrapbook. Several writers seem to have been invited for readings and events at the library, and they wrote letters back to library staff about their experiences.

From the 1950-1976 scrapbook

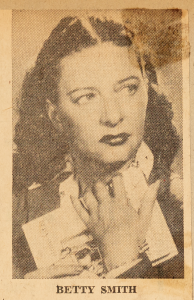

One of the most famous writers that visited was Betty Smith, who is probably best known for her novel A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (there are several materials about her already on DigitalNC, including this video interview). Although she was born in New York, Smith adopted Chapel Hill as her home town later in life and is still buried in the Chapel Hill Memorial Cemetery. Along with the card that she sent to library staff (pictured above), the scrapbook includes a newspaper clipping with an interview of Smith where she encourages Chapel Hill to resist the push for industry and to preserve its small-town character.

“I hate to see commercialism,” she said. “They come in and tear up trees that took 200 years to grow, and pile them up and burn them to get rid of them. Then they stick out little trees—with wire holding them up. Why couldn’t we have a shortage of bulldozers!”

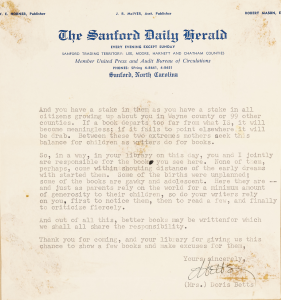

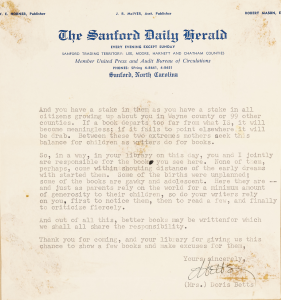

The second half of a letter from Doris Betts

Another well-known author included here is Doris Betts, who served as an English and creative writing professor at UNC Chapel Hill. Betts was born in Statesville, attended UNC Greensboro and eventually settled in Pittsboro. In her literary career, she produced six novels, three short story collections, a Guggenheim Fellowship, three Sir Walter Raleigh Awards and the N.C. Medal for Literature. Her archive is now part of the UNC Chapel Hill Southern Historical Collection at Wilson Library.

Other authors included in the 1950-1976 scrapbook include Inglis Fletcher, Bernice Kelly Harris, Mebane Holoman Burgwyn, Bernadette Hoyle, and Mertie Lee Powers.

You can see the full collection of scrapbooks here. To see more materials from the Wayne County Public Library, you can visit their partner page and their website.

Cheerleaders from The Riviera, 1967.

Thanks to the work of our new partner, the Riverside Union High School Alumni Association, we’ve added several new yearbooks from the Franklin County Training School/Riverside Union High School from 1943-1967. We’ve also included a 1955 graduation program with photos of the graduates.

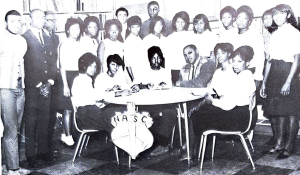

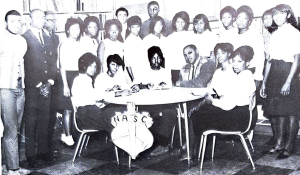

Riverside High School student council (from The Riviera, 1967).

Franklin County Training School began as one of many “Rosenwald schools” in North Carolina—which erected 813 buildings through the project by 1932, more than any other state in the country, according to the North Carolina Museum of History. For background, “Rosenwald schools” were developed by Booker T. Washington and the Tuskegee Institute as a way to improve formal education for Black children in the South. The project soon received funding from Julius Rosenwald, then-President of Sears, Roebuck and Company, resulting in over 5,300 buildings in 15 states.

Although Rosenwald provided significant financial backing, much of the money for these schools came from grassroots contributions by community members. The terms of Rosenwald’s fund stipulated that communities had to raise enough money themselves to match the gift, so George E. Davis, the supervisor of Rosenwald buildings in N.C., often held dinners and events to encourage local farmers to contribute. By 1932, Black residents had contributed more than $666,000 to the project.

Though many schools built in part with Rosenwald Fund grants were designed to be small (typically one to seven teachers per school), Franklin County Training School was once the only Black public high school in the county. As a result, the student body expanded; many students lived nearby, and others were bused from farther away (102). In 1960, the original building burned down, and the school was rebuilt as Riverside Union School and then Riverside High School (103).

James Harris, The Riviera, 1967

“I’d say very jovial, it’s a family type atmosphere. I felt very safe,” James A. Harris, who attended the school from 1955 to 1967, recounted in 2004. “Teachers were very caring and provided not only just classroom instruction, but a lot of values. Teachers were held to a higher standard. If you look at people in the community that people looked up to, [teachers] were right behind the minister. They were held in high esteem.” (From John Hadley Cubbage, 2005.)

When North Carolina racially desegregated schools in 1969, Riverside High School was converted to Louisburg Elementary School. Today, it’s the central office for Franklin County Schools. The building itself is on the National Register of Historic Places (Reference Number: 11001011).

To see all of the materials from the Riverside Union High School Alumni Association, you can visit their partner page or click here to go directly to the yearbooks. You can also browse our entire collection of North Carolina yearbooks by school name and year.

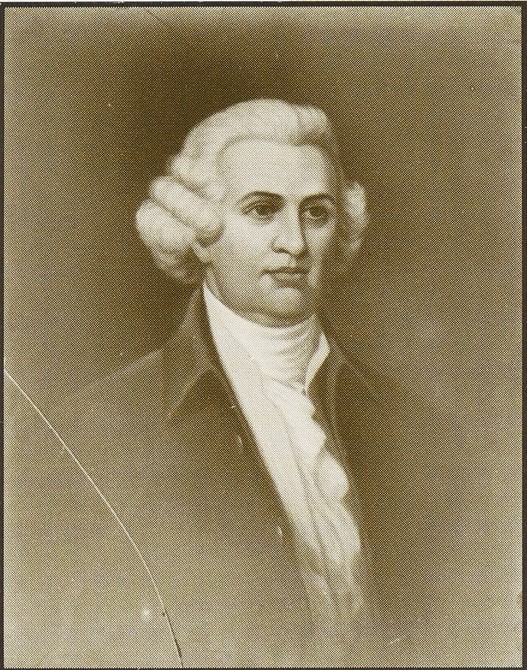

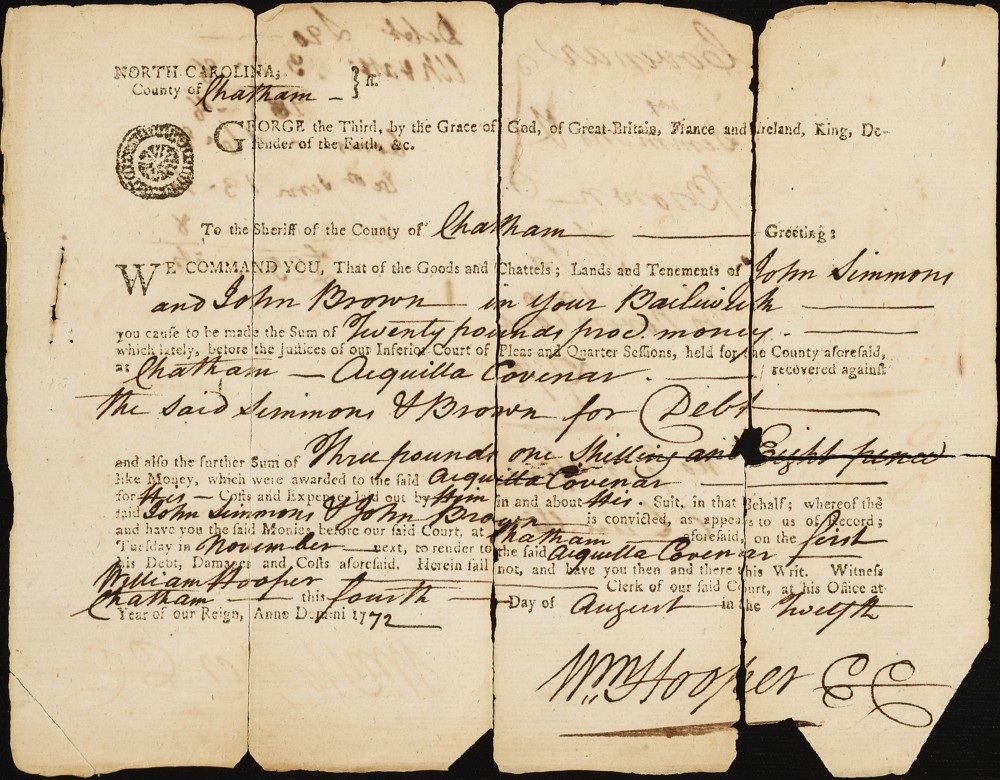

Thanks to our partner, Chatham County Historical Association, batches containing three Moncure and Pittsboro High School yearbooks as well as court summonses signed by William Hooper are now available on our website. These court summonses, created three years before the American Revolution began, are some of the oldest primary source documents available on DigitalNC.

During his position as Chatham County’s first Clerk of Court, William Hooper executed a myriad of legal documents. Over the years, three of these legal documents were donated to the Chatham County Historical Association where they were held until 2022. In March 2022, the historical association learned that the Hooper court summonses should have originally been transferred to the State Archives since they are responsible for the preservation of records from all counties, state agencies, and government offices in North Carolina—no matter how old the material. After contacting the State Archives, a representative came to collect the three court summonses from the association. At the State Archives the court summonses are being curated and properly preserved. To learn more about the Chatham County Historical Association’s experience with the State Archives, please read the association’s post here.

William Hooper was one of North Carolina’s three signers of the Declaration of Independence and the North Carolina representative member of the Continental Congress from 1774 to 1777. After graduating from Harvard College in 1760 at the age of 18, Hooper went on to study law under James Otis. In 1764, he temporarily settled in Wilmington, North Carolina to begin practicing law. Popular with the people of the area, he was elected recorder of the borough two years after his arrival in 1766. From May 1771 to November 1772, Hooper served as Chatham County’s first Clerk of Court despite never living in the county. In the years leading up to the American Revolution, Hooper traveled across North Carolina as a lawyer, was appointed deputy attorney general of the Salisbury District, and officially entered into the political world when he represented the Scots settlement of what is currently named Fayetteville in the Provincial Assembly in 1773. In the years leading up to the American Revolution, Hooper traveled across North Carolina as a lawyer, was appointed deputy attorney general of the Salisbury District, and officially entered into the political world when he represented the Scots settlement of what is currently named Fayetteville in the Provincial Assembly in 1773.

On July 21, 1774, he was elected chairman and presided over the selection of a committee to a call for the First Provincial Congress. When the Congress met, Hooper was chosen as one of three delegates that would represent the state of North Carolina at the First Continental Congress. Over the next two years Hooper served as a delegate for both the Provincial and Continental Congress on various committees including one that was in charge of stating the rights of colonies, one that reported on legal statutes affecting trade and commerce in the colonies, Thomas Jefferson’s committee to compose the Declaration of Independence, a committee for the regulation of the secret correspondence, and many more. Despite Hooper’s triumphs in the political sphere early in the revolution, his return to Wilmington in early 1777 due to contracting yellow fever began a steady decline for his political career and, consequently, his health.

Hooper attended the General Assembly, serving on multiple committees as the member for Wilmington each year from 1777 until the city was taken over by the British in 1781. Considered a fugitive by the British, Hooper hopped to various friends houses in the Windsor-Edenton area while his wife Anne and children fled to Hillsborough. Reunited in 1782 in Hillsborough, the family was permanently removed to the backcountry where they remained out of touch with national and state current events. In that same year, Hooper’s election to General Assembly as member for Wilmington was declared invalid (presumably since he was now in Hillsborough). The following year, he ran for the General Assembly’s Hillsborough seat and lost. In spite of this loss, Hooper ran again in 1784 and was this time elected. He would serve in the General Assembly as a representative for Hillsborough until 1786.

Although he enjoyed some political success since he left Philadelphia in 1777, Hooper was devastated when he was not elected a delegate to the 1788 Constitutional Convention. Certainly adding to his feelings of discontent, the convention met at Hillsborough’s St. Matthew’s Church, which was within sight and sound of Hooper’s house. As a result of what he saw as a failure, Hooper began to drown his feelings of disappointment in rum. At the age of 48, Hooper died the evening before his daughter’s marriage in 1790.

To learn more about the Chatham County Historical Association’s experience with the State Archives, please read the association’s post here.

To learn more about the Chatham County Historical Association, please visit their website.

For more yearbooks from across North Carolina, visit our yearbook collection.

To learn about William Hooper’s life in more depth, please view NCpedia’s entry on William Hooper.

Information in this blog post was taken from the NCpedia William Hooper entry.

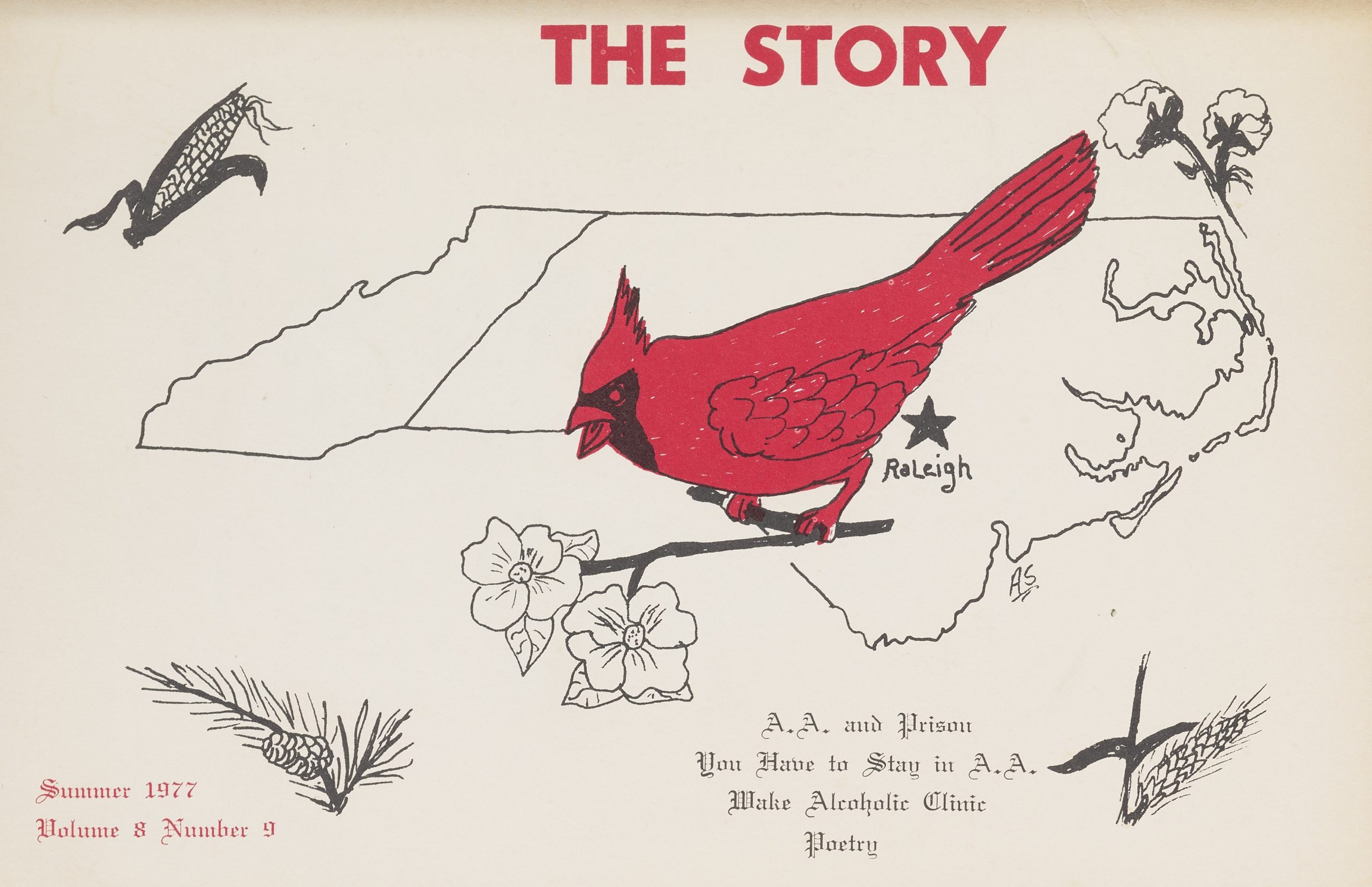

Thanks to our newest partner, the North Carolina General Service Committee Archives, 47 issues of the publication The Story are now available on our website. The Story was published quarterly by inmates of the State Department of Correction in Raleigh, North Carolina. A majority of the entries in these issues focus on Alcoholics Anonymous in prison, the struggles of sobriety, as well as personal achievements and stories. Each issue also features several small drawings and beautiful covers.

To learn more about the North Carolina General Service Committee Archives, please visit their website.

To view more North Carolina publications, please click here.

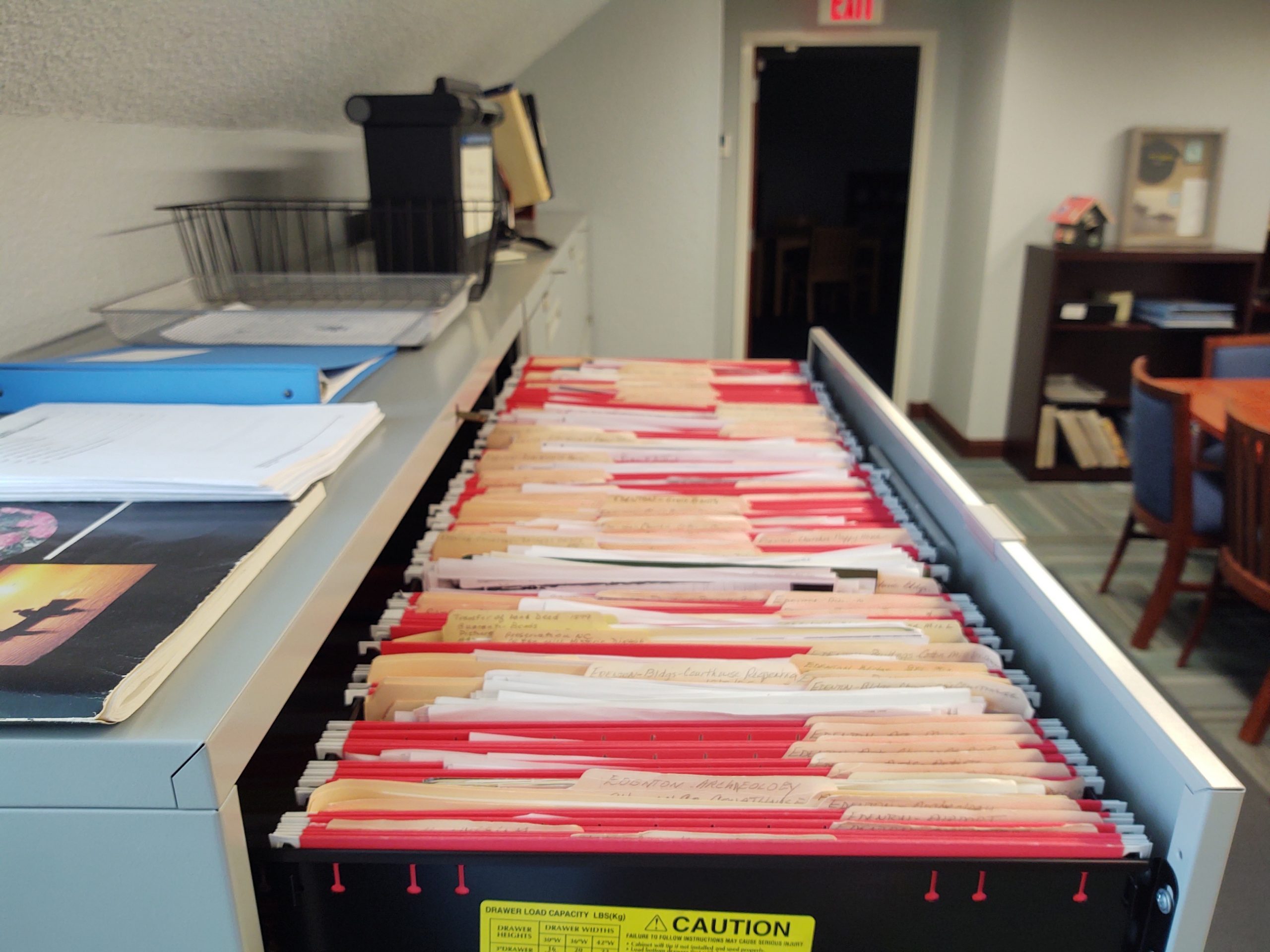

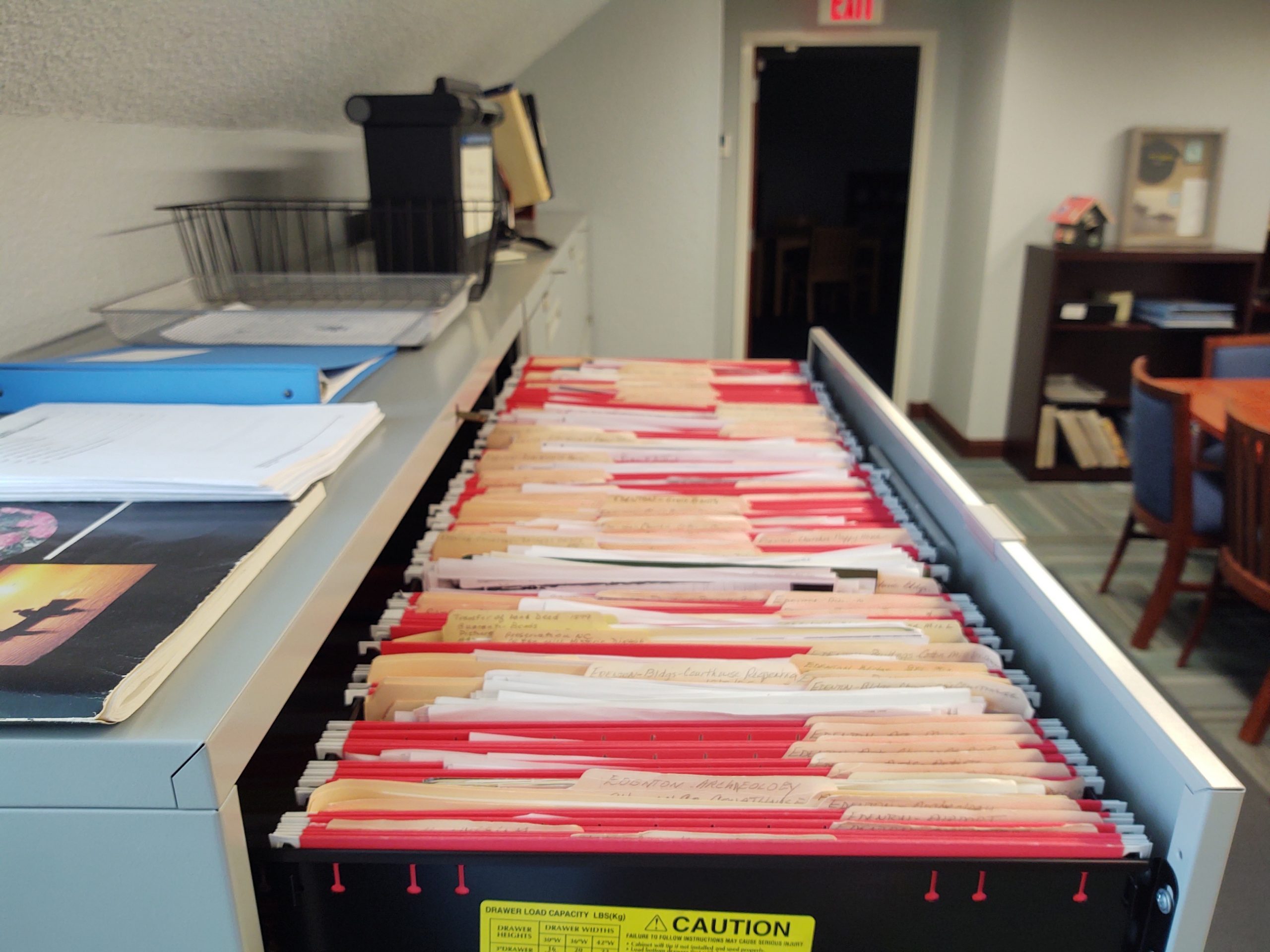

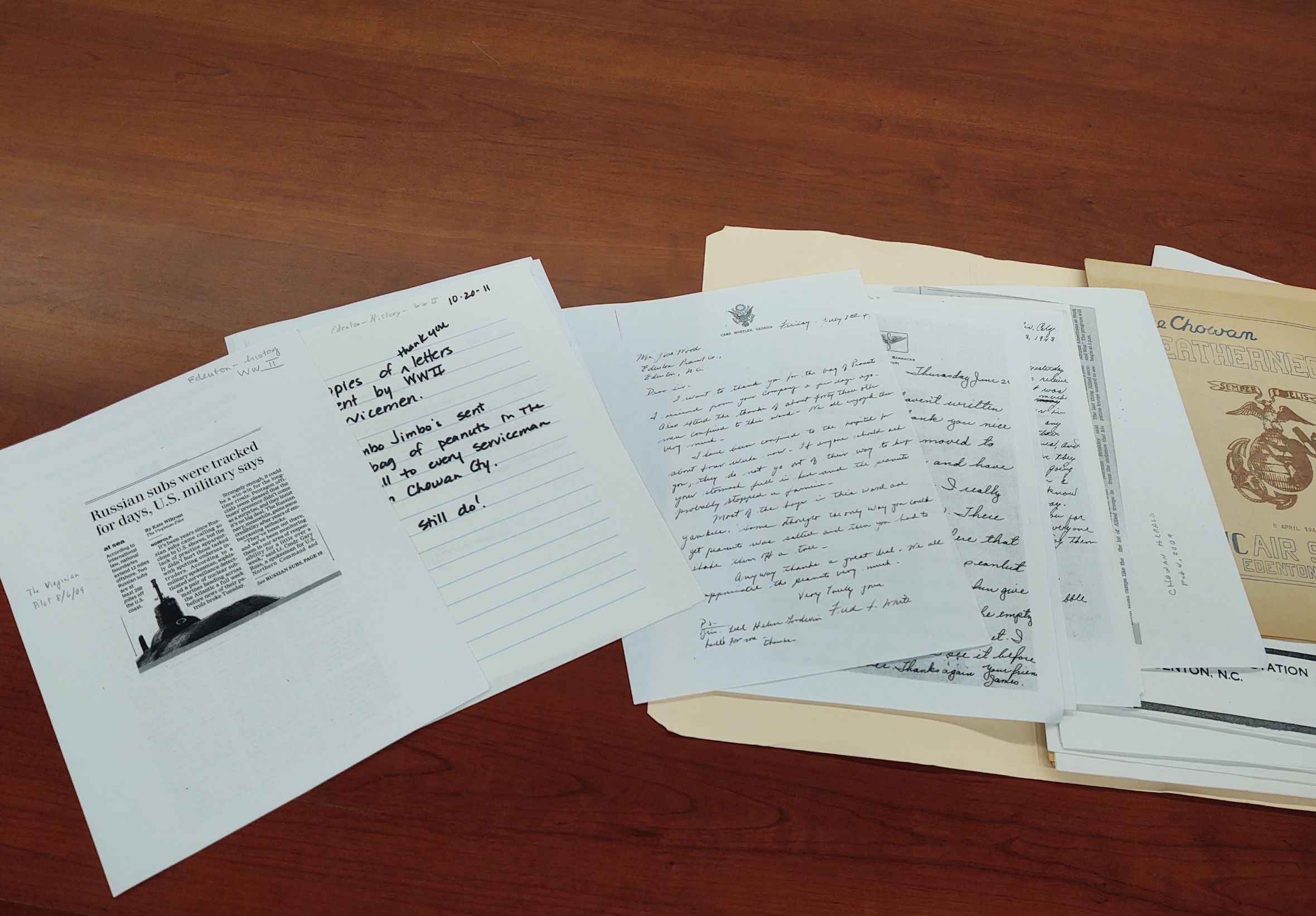

Vertical files are groups of subject-based materials often compiled over time to help an organization’s staff with frequent reference questions or research. Like the example above at Shepard-Pruden Library in Edenton, NC, they’re typically housed in filing cabinets. They are a good place to store items that wouldn’t necessarily be cataloged or accessioned (individually and formally documented by the institution) but are valuable for research. Inside you might find photographs, clippings, family trees, pamphlets, handwritten notes – but because the contents accumulate over time you can find any number of surprises inside.

Vertical files are groups of subject-based materials often compiled over time to help an organization’s staff with frequent reference questions or research. Like the example above at Shepard-Pruden Library in Edenton, NC, they’re typically housed in filing cabinets. They are a good place to store items that wouldn’t necessarily be cataloged or accessioned (individually and formally documented by the institution) but are valuable for research. Inside you might find photographs, clippings, family trees, pamphlets, handwritten notes – but because the contents accumulate over time you can find any number of surprises inside.

Vertical files are also the worst – for digitization that is. The same thing that makes them valuable for research – their convenience, their long term growth, and the variety of contents – makes them incredibly challenging to scan. If you’re interested in digitizing vertical files, we have suggestions! These have been compiled from our own experience at NCDHC along with the experiences of a number of our partners who kindly responded to a recent email asking for advice.

When facing full filing cabinets you may be tempted to dive in right at the beginning and get going, but we always suggest starting with a pilot project using a subset of materials. We can’t emphasize this enough! It’ll give you a sense of workflow, help you establish how you’re going to name and organize the scanned files, and uncover obstacles you didn’t anticipate. If it goes poorly, you can back out without losing a large investment. The suggestions below can be used for a pilot and for a full-fledged project.

Suggestion 1: Prep First, Thank Yourself Later

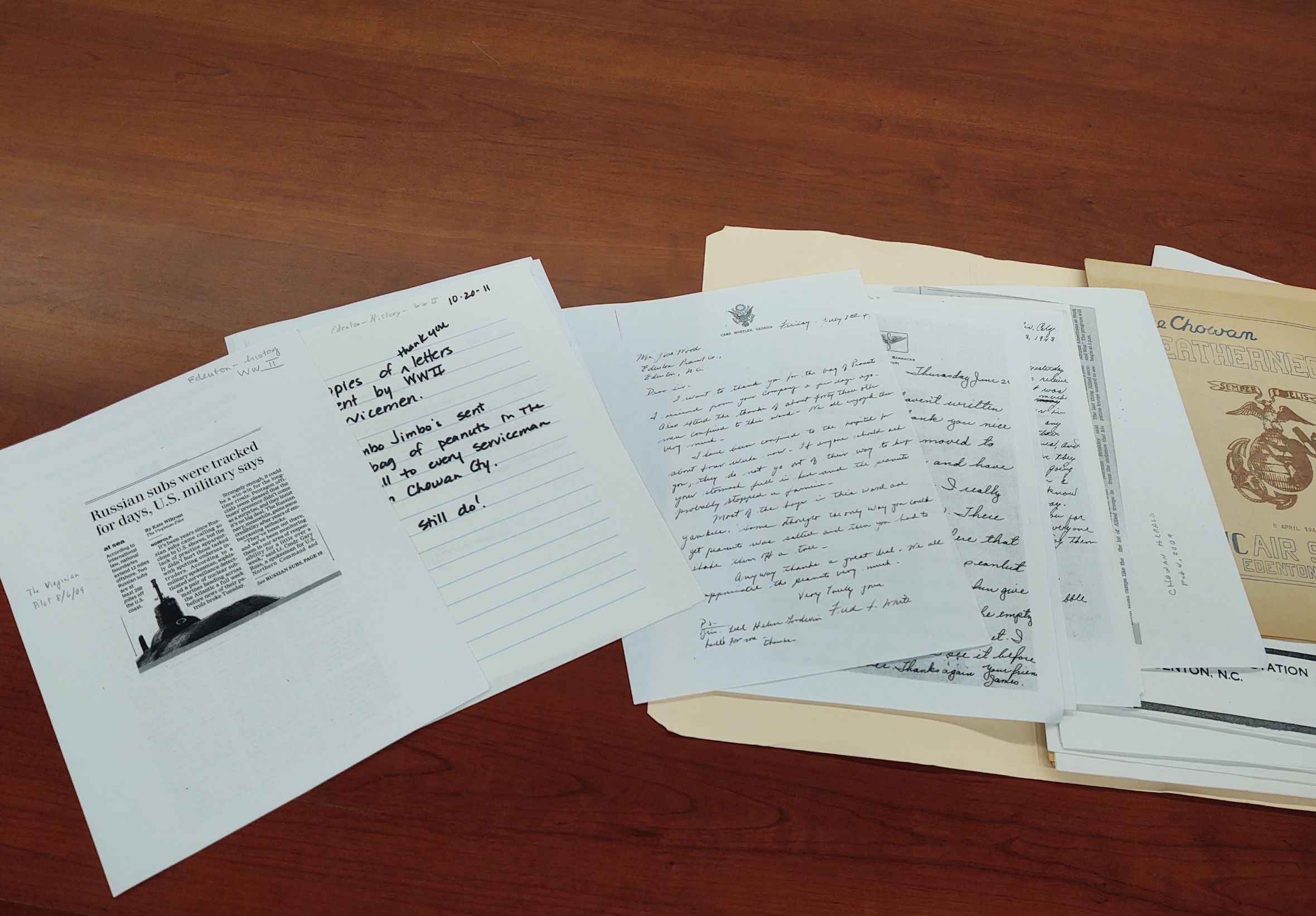

Here’s an example of a vertical file with newspaper clippings, letters, and publications about World War II. From the collection at Shepard-Pruden Library in Edenton.

Scan it all or be selective? Decide if you want to go from beginning to end or to be selective about what you’ll scan. There’s no right answer but each way has ups and downs. This decision will be subject to your users’ needs and your local resources.

Scan it all? Is there enough high value and unique content in your vertical files to warrant scanning everything? For example, some newspaper titles have been digitized in their entirety and are full text searchable (like those available at DigitalNC or Chronicling America) so you might decide that scanning clippings from those same papers is superfluous. As another example, many books published before 1924 in the United States are available online at the Internet Archive or through a simple search in your internet browser. If your files have a lot of book excerpts you may want to skip those.

Be selective? Being selective can be more time consuming and you may unintentionally miss items that would be of use, but it can be appropriate if you’re trying to simply scan items related to one or two topics or for a particular event. It is also a great option if you don’t have a lot of time or resources but want to help give access to high demand files.

First pass for organization. Go through the files in a first pass, during which you’ll assess the files’ contents, sort them in a way that will make scanning easier, and prepare the different formats for scanning. Here are some tasks to complete as you make a first pass:

- Pull out items to be cataloged separately. As your organization’s collection strategies have changed over time you may find materials within the files that should be pulled out and cataloged or accessioned independently. For example, perhaps you are a library where pamphlets were previously stuck in vertical files but are now cataloged and put on the shelf. These can be pulled out and dealt with separately.

- Weed. Take this opportunity to weed out duplicates and look for misfiled items.

- Group items with copyright or privacy concerns. I talk about this in more detail below, but if you plan to put these files online, you may want to skip scanning items that would be too risky or unethical to share online. You could put them towards the back of each file with a divider that indicates they should be either reviewed in more detail or skipped while scanning.

-

Ashlie, an NCDHC staff member, uses a microspatula to pry up staple legs. License: CC0

Remove staples and fasteners. The caveat here is that you should only do this with materials you’re sure you’re ready to scan. One partner mentioned that staff had removed staples and paperclips from a large quantity of files, but then the project got stalled. Because the vertical files were still in use, this led to papers being misfiled, shuffled out of order, and lost.

- Organize by type then by date. Within each file, organize individual items first by format of item, then by date. Group all of the photographs. Put like sized publications together. Group all of the single page items, all of the clippings. Putting like sized types together will speed up the workflow, saving time when scanning by streamlining your efforts at cropping. Once you’ve grouped things by type, within each group put things in date order (if dates are available). This will help you when you make the scans available.

Suggestion 2: Prepare for the Digital Files

Unless you don’t have that many vertical files (or you have a LOT of time and help) think of each vertical file as a single unit. Here’s what I mean by this. If you have a vertical file about a popular local landmark called the “Turtle Log,” and it includes a few photos, some clippings, and a handwritten narrative, all of those scans would be kept together in a virtual group, folder, or album just as they are in real life. When you describe that group/folder/album either in an internal or online database, you’d describe the unit as a whole, rather than describing each individual photo, clipping, or narrative. This will save a ton of time.

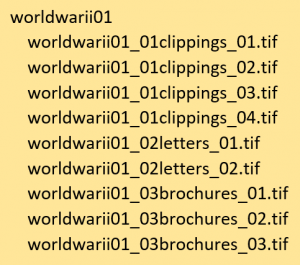

With this in mind, you’ll want to think of a file naming scheme that will keep all of these digital groups organized. Thankfully, file systems mimic files in real life, with the use of folders. Make sure you have a consistent naming convention for files and folders that ensures everything sorts appropriately. On the right is a quick example of how you might decide to name your files. This example is very basic – you could choose to give more detail, include known dates. But note the numbers (01, 02, etc.) included that will make the files sort in order.

With this in mind, you’ll want to think of a file naming scheme that will keep all of these digital groups organized. Thankfully, file systems mimic files in real life, with the use of folders. Make sure you have a consistent naming convention for files and folders that ensures everything sorts appropriately. On the right is a quick example of how you might decide to name your files. This example is very basic – you could choose to give more detail, include known dates. But note the numbers (01, 02, etc.) included that will make the files sort in order.

Suggestion 3: Determine How You’ll Work with Additions

If you intend to keep these vertical files active after scanning, you’ll need to figure out how to denote what’s been scanned and what you’ll do with new additions to the files. A light pencil mark or some other non-permanent note on the back of all scanned items can signal what’s been scanned. Decide if you have the time and staff to scan new additions before filing new donations or if you plan to do that wholesale at a later date. It might also be helpful to have a marker of some sort that you can insert into the file cabinets that lets researchers and staff know about files that have been removed for scanning and whether or not they can still request them.

Suggestion 4: You Should Scan these In House. Or You Shouldn’t.

I wish I could give a single way forward here, but like so many things the answer to whether or not to outsource scanning depends on your situation. Here are a few considerations for the two routes.

Scanning in house. This gives you a lot of flexibility. You can work on the project over time. For active files, they’ll be close at hand if needed. Your staff will gain experience scanning, if they don’t already have it.

Unless you can afford an overhead scanner or camera mount setup, scanning vertical files on a flatbed or other multifunction machine will make a very long process a lot longer. Sheetfed scanners can speed things up a little but only for extremely uniform, non-unique materials that are in good shape. Because the project is large, if you don’t have dedicated scanning staff (or even if you do) be prepared for the contents of multiple file cabinets to take years to scan. You may also need to hire new staff or reskill current staff to do this work, trading this for other duties they currently complete.

Outsourcing scanning. Outsourcing can mean a quicker outcome because the organization doing the scanning will have dedicated workflows and equipment for high volume output. If you don’t have digitization expertise on staff, their expertise can be helpful for avoiding pitfalls.

Unless you are working with an organization that typically scans special collections, the variety of formats can be a challenge and frequently increase the cost. Companies that specialize in corporate files will claim attractively inexpensive prices for scanning but they are frequently used to working with homogenous typing or copy paper. Be sure to interrogate them regarding their expertise, showing them examples and even asking for a quote after they scan a subset. Make sure they offer digital files of a quality and in file formats that you can use into the future.

Suggestion 5: Decide About Your Access Priorities and the Rest will Follow

As we’re fond of saying, digitization is the easy part. Even in a project of this size and complexity, the scanning and preparation of the digital files is more straightforward then what comes next. Here are confounding factors to take into account when you consider how you’ll provide access to the digital vertical files.

Full Text Search

Full Text Search

Full text search greatly increases the usefulness of digital vertical files. It’s one of the most cited reasons for scanning them in the first place. To be able to search full text within a scanned document, you’ll need to run that digital file through software that recognizes the text and then either embeds it within the file or stores it separately. (Note that this will only happen with typewritten text – accurate automated recognition of handwriting isn’t widely available at this point.) Here are two different options:

- Some institutions choose the PDF format for their vertical files. Software like Adobe Acrobat (not to be confused with the freely available Adobe Reader) will recognize text within a PDF. However PDFs are made for easy transmission and sharing, not for longevity and quality. We recommend that you scan initially to a higher quality or lossless format, and then, if it fits your goals and resources, create derivatives like PDFs. The upside of PDFs is that many desktop and laptop computers can natively search across PDFs. This means you could have them searchable locally, say on a reading room computer, and not necessarily have to provide internet access.

- Alternatively, you can use a system that can store both the text recognized in an image and the image itself and then link them together. Some library or museum catalogs will do this, or you’ll need a content management system. This means additional ongoing costs and the need for technological infrastructure and expertise. But with these types of systems you can provide full text search of your files on the internet.

Copyright and Privacy

Copyright is one of the biggest confounding factors related to making vertical files accessible. Depending on how old your files are, it’s likely that there are materials in there that will be in copyright. If you want to post copyrighted materials on the internet, your organization will need to assess the amount of risk you’re willing to accept. Some items are riskier than others. Regardless, whoever is working on your vertical files will need training and the authority to determine what can and should go online and what should not. Here are a few resources to help get you started:

In addition to copyright, you should always consider privacy concerns. For some of the non-published items in your vertical files, the donations or additions were made with the expectation of local use by a single person or small group. Family history documents that discuss recent events are an example of the type of item you may judge to be too personal for broad consumption without the permission of the creator. There may be documents that share information about communities that would prefer they not be shared broadly. These are all good things to assess as you do your first pass.

Suggestion 6: Find Examples and Friends

Here are some examples of digitized vertical file collections online. These are large projects with a goodly number of staff and funding involved, so take that into account as you look. Note that the files are put online whole rather than breaking out individual items.

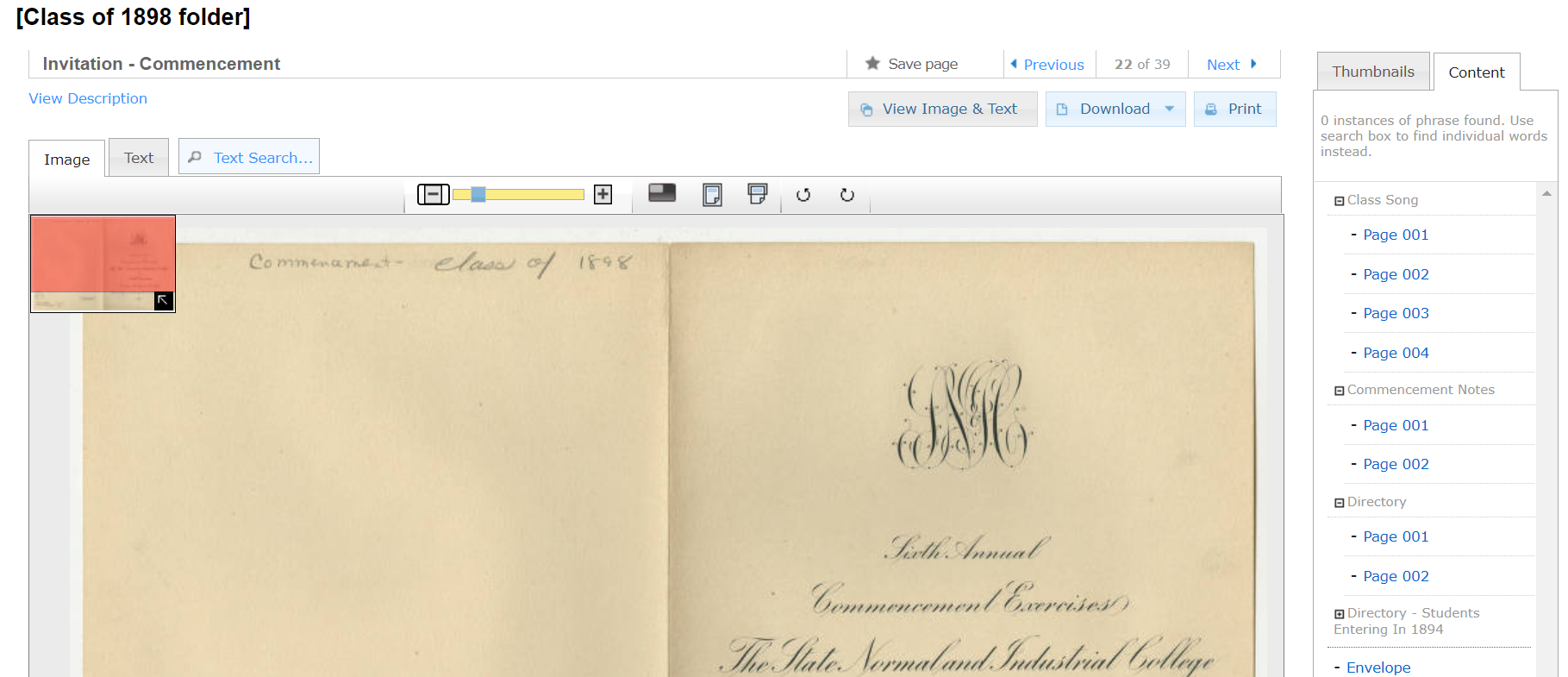

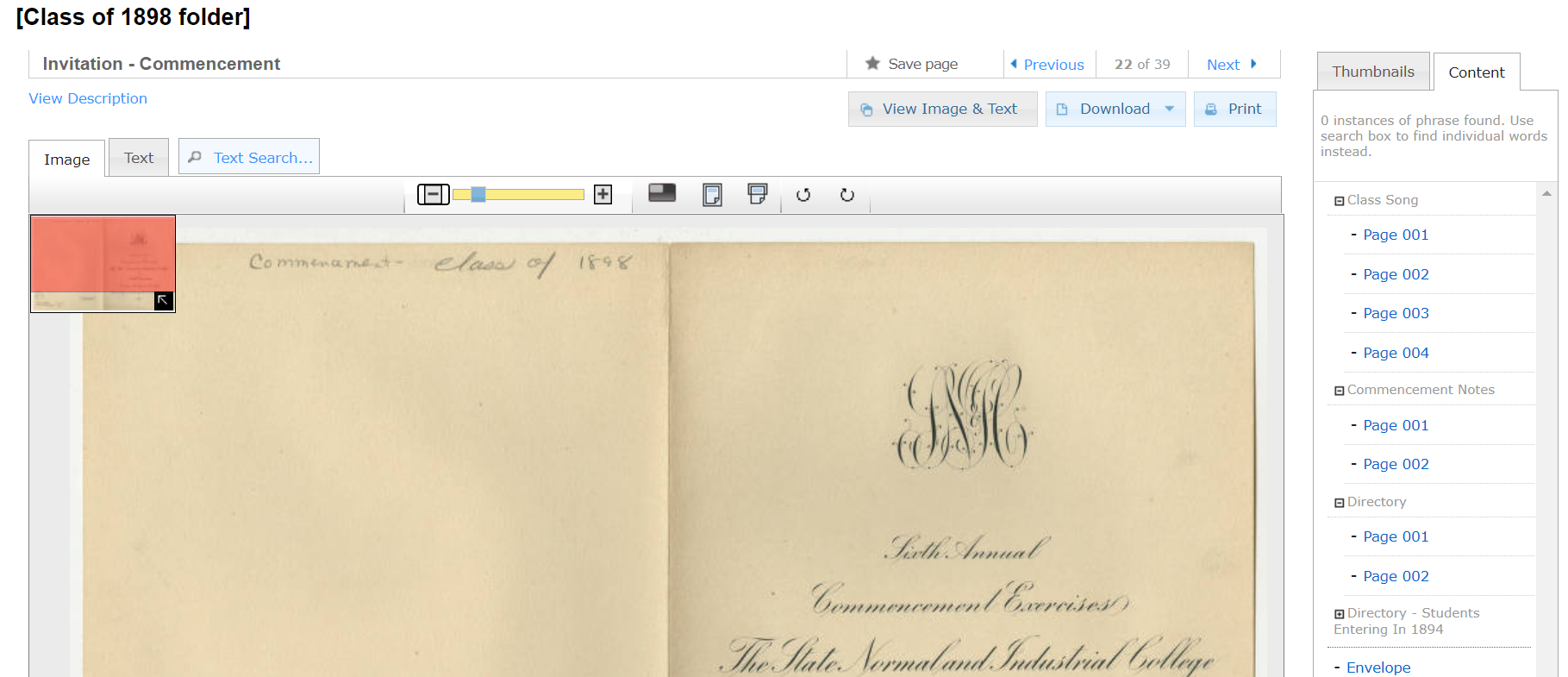

This first example comes from the Digital Collections of the University Libraries at UNC-Greensboro and showcases their “class folders.” UNC-G has done quite a bit with vertical files of various types, but this is a great example of folders that have a variety of items grouped by subject. These items are in a system called CONTENTdm, which is specifically designed to host special collections.

This invitation is one of a number of items in the vertical file entitled “Class of 1898.” You can see the item title at the top and a list of the different items inside on the right.

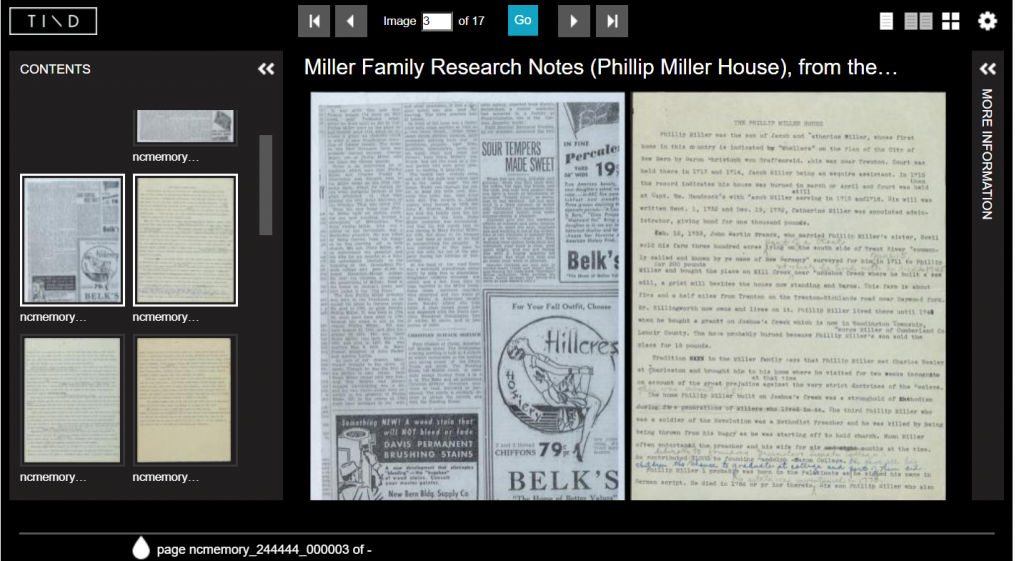

We’ve also done some vertical files at NCDHC, and you can take a look at an example here. This is from a large collection of vertical files shared by the Kinston Lenoir-County Public Library. Our system is called TIND.

This screenshot shows a large view of a newspaper clipping alongside a typewritten manuscript from the Sybil Hyatt Papers. To the left are thumbnails showing other items in this particular file.

Keep in mind that both of these systems are made for hosting large numbers of special collections items and, like a library or museum catalog, cost money and staff to maintain. While it’s outside of the scope of this article, you can take a look at another post we did regarding how to share your digital files.

For any digitization project, we heartily recommend trying to find friends and peers at area or regional organizations. Ask if they have vertical files or digitization projects (or both?!). A quick phone call or email can help you avoid duplication of effort, at the least, and may gain you advice or a collaboration. You can even choose to share staff or other resources, or collaboratively apply for funding. We also like to be friends! If you’ve made it this far and still want to digitize, but you have questions or would like additional advice, feel free to get in touch.

Vicki Coleman, Dean of Library Services at the F. D. Bluford Library, at North Carolina A&T State University

This year marks the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center’s 10th anniversary, and to celebrate we’ll be posting 10 stories from 10 stakeholders about how NCDHC has impacted their organizations.

Today’s 10 for 10 post is from Vicki Coleman, Dean of Library Services at the F. D. Bluford Library, at North Carolina A&T State University. We’ve partnered with NC A&T (Library home page | NCDHC contributor page) to digitize yearbooks, catalogs, and student newspapers. The Library also has their own extensive digital collections online, where you can find faculty research, agricultural history, and history about NC A&T. Read below for more about our partnership with NC A&T.

___

Happy 10th anniversary to the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center!

Over the past decade, the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center (NCDHC) has played a vital role in helping the F.D. Bluford Library at North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University (NC A&T) ensure the success of its digital conversion projects. More specifically, the NCDHC’s digitization services have aided Bluford Library by providing the infrastructure to create thousands of preservation-quality digital images and other historical materials that are now accessible by students, faculty and researchers world-wide.

Working collaboratively with the NCDHC has opened opportunities for Bluford Library to give visibility to the wealth of history stored in its archive and to the many resources accessible from the DigitalNC website. Listed below are examples of how some digitized collections are used:

- The university’s digitized yearbooks (1939-2013), catalogs and bulletins (1895-2013) and student newspaper (1915-2010) serve as indexes, directing researchers to names, places, photos and historical events that helped shape the university, the surrounding Greensboro community, and the history of African-Americans with regards to higher education and the civil rights movement.

- In 2015, I oversaw the publication of NC A&T’s pictorial history book commemorating the university’s 125th anniversary. When it came to the digitization of some of our most brittle materials for inclusion in the book (e.g., minutes from an 1891 Board of Trustees meeting) it was the NCDHC that got it done.

- Over the past three years, James Stewart, the Archives and Special Collections librarian at Bluford Library, has taught more than 300 students how to access community histories about NC A&T and African-American history via the DigitalNC website.

- This past summer, Mr. Stewart and I conducted research pertaining to the naming of all the buildings and streets on the NC A&T campus. We were able to locate much of the historical information in the A&T Register, the NCA&T student newspaper that was digitized by the NCDHC and by searching the Newspapers collection on the DigitalNC website.

The NCDHC has advanced Bluford Library’s efforts to make historical materials accessible online by providing visionary guidance, high-level expertise and access to state of the art scanning equipment. I appreciate the great skills of the many individuals that make up the NCDHC and look forward to continuing a productive partnership with them. Congratulations to the NCDHC on its tenth anniversary and I await with pleasure another 10 years of remarkable achievements in increasing open access to the state’s cultural heritage.

Staff at Shepard-Pruden Memorial Library (L-R) Destinee Williams, Claudia Resta, Brandy Goodwin, Larry the Mascot, and Jennifer Finlay

This year marks the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center’s 10th anniversary, and to celebrate we’ll be posting 10 stories from 10 stakeholders about how NCDHC has impacted their organizations.

Today’s 10 for 10 Q&A is from Jennifer Finlay, Chowan County Librarian at Shepard-Pruden Memorial Library. (Library’s home page | NCDHC contributor page) We’ve worked with the Library to digitize issues of The Chowan Herald out of Edenton, NC. We were happy to work with them in a successful trial project to accept additional funds from partner organizations for newspaper digitization, too. Read below for more about our partnership with the Shepard-Pruden Memorial Library.

What impact has NCDHC had on your institution and/or on a particular audience that means a lot to you?

We had the good fortune of being chosen to have part of our local newspaper, The Chowan Herald, digitized by NCDHC in 2018. I then proposed an innovative approach to digitizing more years of the paper by having our local historic preservation grantors help fund more years. NCDHC had not done this in the past and the Shepard-Pruden Memorial Library was part of a pilot program. This helps small, rural and lightly funded libraries to be able to do digitization without having to learn all the technical aspects of digitization and hosting the results.

Do you have a specific user story (maybe your own!) about how DigitalNC has boosted research or improved access to important information?

This saves us so much time when we get the phone calls from out of state asking about a Chowan Herald article. We no longer have make time to go upstairs, fire up the microfilm machine, try and find an article with limited reference information and no index. We can either look for it ourselves while on the phone or give the link to the caller and they can have fun reliving the past.

If you were asked to “describe what makes NCDHC great” in a few words, what would they be?

NCDHC as a website is so much more user friendly than the state archives. (Sorry state archives). I love that Lisa Gregory and the decision makers of DigitalNC took a chance on us and tried something new.

Thanks to the staff at the Outer Banks History Center, we now have a complete run of the 1941 Tyrrell Tribune available online. These papers were scanned at our office in Elizabeth City.

Thanks to the staff at the Outer Banks History Center, we now have a complete run of the 1941 Tyrrell Tribune available online. These papers were scanned at our office in Elizabeth City.