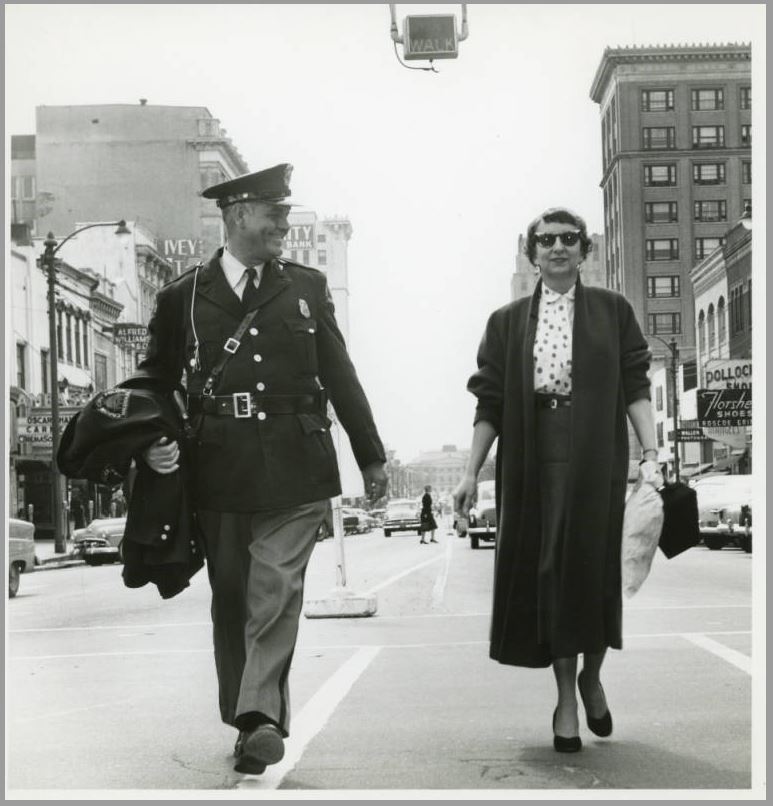

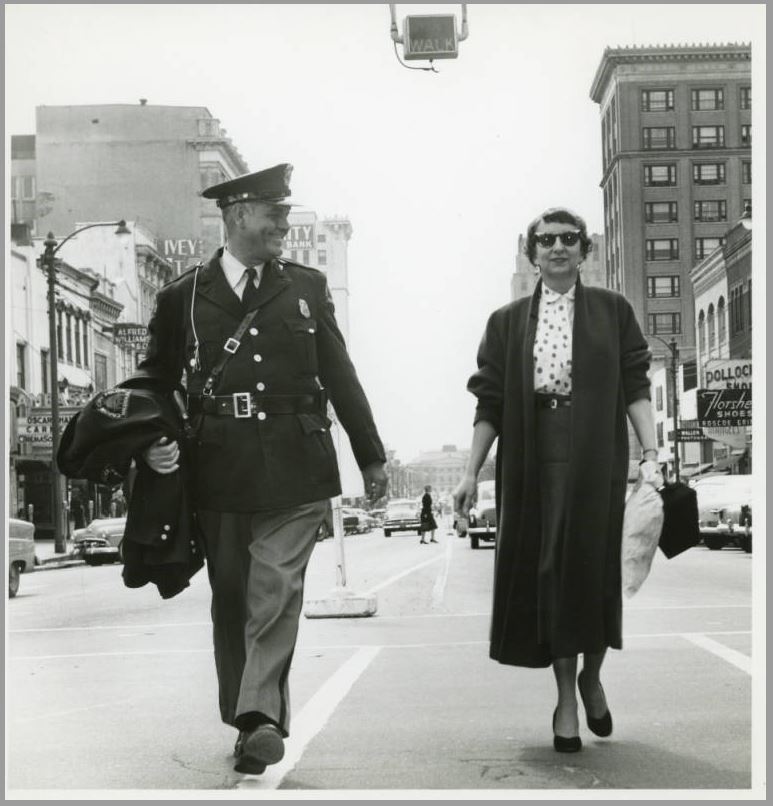

Madlin Futrell and a police officer walk down Fayetteville Street in Raleigh in the late 1950s

Back in August, DigitalNC was excited to road-trip over to Raleigh and test out our plan for onsite digitization at the City of Raleigh Museum whose staff kindly agreed to be our pilot location. The collection we worked on while there was the Madlin Futrell Photograph Collection, a great collection of photographs primarily from the 1950s. Madlin Futrell was a professional photographer who lived in Cary, NC and worked for the Raleigh Times, the North Carolina Office of Archives and History (now part of the North Carolina Department of Cultural and Natural Resources), and on a contract basis for several other institutions. The photographs we digitized include location photographs of the Raleigh area, employees in the NC Office of Archives and History, historic sites around the state, and of President Eisenhower’s visit to the state in 1958. They offer not only a look at places around NC in the 1950s but also a look at the life of a career woman in mid 20th century North Carolina.

Staff of the Hall of History in Raleigh, North Carolina. Photograph was taken in April 1960.

To view all the photographs digitized from the Futrell collection, go here. To view other photographs on DigitalNC, visit our Images of North Carolina site here. And if you’re interested in learning more about our onsite digitization program, please read about it here and apply if interested!

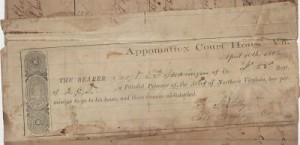

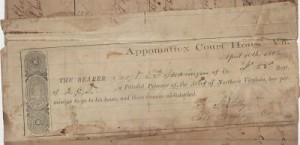

One of the more recent items we’ve digitized from the Stanly County Museum is the “Copy of Robert E. Lee’s Farewell Address and Parole Slip of Confederate Soldier E. S. Swaringen, 1865.” It’s a self-explanatory title, and despite the historic nature of Lee’s address the Parole was probably of equal or more import to Swaringen. The well-worn parole pass is pictured below.

Dated April 10, 1865 at Appomattox Court House, Va., the pass reads: “The Bearer, Sargt E. S. Swaringen of Co. “I” 52nd Regt. of N. C. D., a Paroled Prisoner of the Army of Northern Virginia, has permission to go to his home, and there remain undisturbed.” It is signed S[amuel]. Lilly.

After Lee’s surrender, over 28,000 parole passes like this one were given out to Confederate soldiers who agreed not to fight — who would give up their arms and proceed home. The blank passes were printed in the field, the operation being directed by Major General John Gibbon who recalled the difficulty of producing so many in such a short period of time. It’s interesting to think about printing logistics compared with an event as momentous as the end of a war. Printing and filling out those passes would be like supplying every person in the city of Sanford NC with a small form within 24 hours.

E. S. Swaringen, the bearer of the pass, was Eli Shankle Swaringen or Swearingen (1836-1913) of Stanly County, North Carolina. The Swaringen family was and is prominent in Stanly County; William Swaringen was one of the first justices of the peace. During the Civil War, the 52nd Regiment, of which Eli was a part, was organized on 22 April 1862 near Raleigh. You can read a more extensive description of the Regiment’s activities in Volume 3 of the Histories of the Several Regiments and Battalions from North Carolina, in the Great War 1861-’65, p. 223 [271 online].

Swaringen and family are buried at Randall United Methodist Church in Norwood, North Carolina, and his tombstone, albeit slightly hard to read, is pictured here.

You can see more Stanly County Museum items at digitalnc.org.

This week we have another 40 newspaper titles and thousands of issues up on DigitalNC, including over 1,000 issues from The Messenger and Intelligencer from Wadesboro, the birthplace of Piedmont blues musician Blind Boy Fuller (read a brief biography about Fuller here). In this post we have some interesting new information regarding the blues legend’s birth!

Via John Edwards Memorial Foundation Records (PF-20001), Southern Folklife Collection, Wilson Library

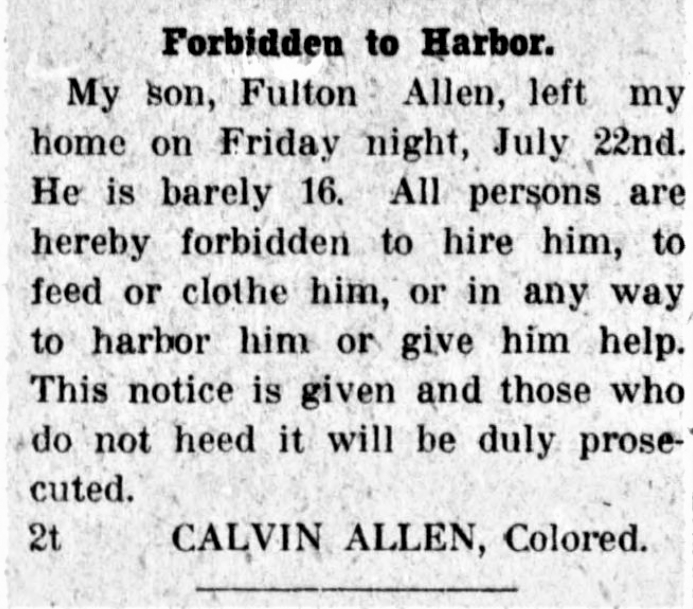

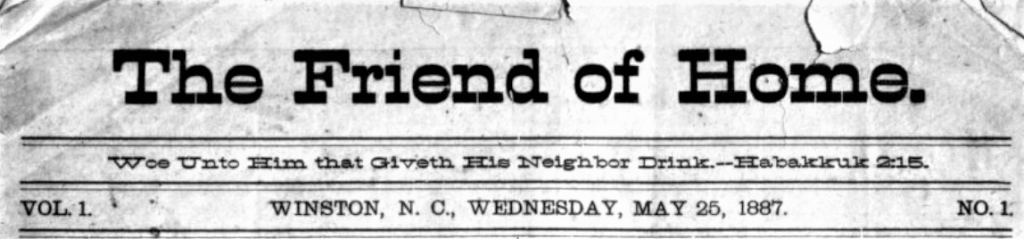

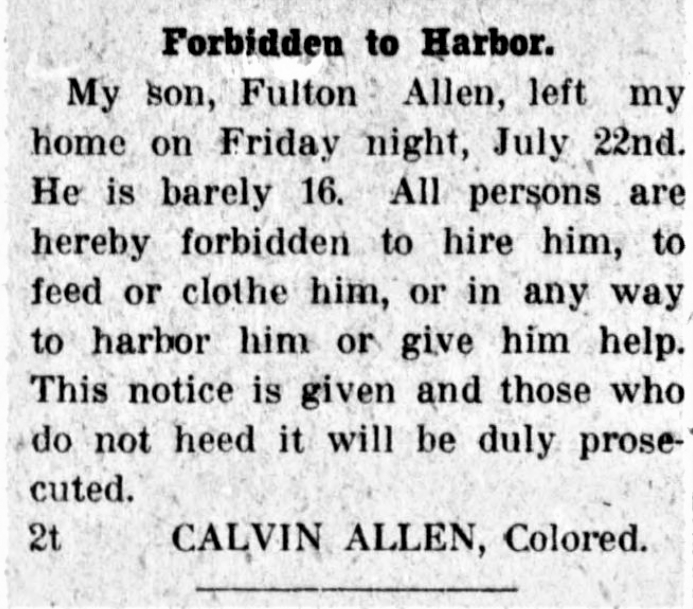

Blind Boy Fuller was born Fulton Allen to parents Calvin Allen and Mary Jane Walker in Wadesboro, North Carolina, but the actual date of his birth is very much up for debate. The date of July 10 seems to be generally agreed upon, but the actual year tends to differ. While there are some sources that put it at 1904, folklorist Bruce Bastin puts Allen’s date of birth at July 10, 1907 based on statements from the North Carolina State Commission for the Blind, the Social Security Board, and the Durham County Welfare records. However, his 1941 death certificate states that he was 32 years old when he died, putting the year of his birth at 1908.

Rockingham Post-Dispatch, July 28, 1921

What we found makes things a little interesting. After the family relocated to Rockingham sometime in the early 1900s, his father posted a notice in the July 28, 1921 issue of the Rockingham Post-Dispatch that would suggest that none of these are accurate. The notice supports the idea of a July birthday but implies that, being 16 years old, he would have actually been born in 1905.

Bruce Bastin is the author of Red River Blues: The Blues Tradition in the Southeast and Early Masters of American Blues Guitar: Blind Boy Fuller with Stefan Grossman. The Bruce Bastin and Stefan Grossman Collections are housed here at UNC as part of the Southern Folklife Collection.

Over the next year, we’ll be adding millions of newspaper images to DigitalNC. These images were originally digitized a number of years ago in a partnership with Newspapers.com. That project focused on scanning microfilmed papers published before 1923 held by the North Carolina Collection in Wilson Special Collections Library. While you can currently search all of those pre-1923 issues on Newspapers.com, over the next year we will also make them available in our newspaper database as well. This will allow you to search that content alongside the 2 million pages already on our site – all completely open access and free to use.

This week’s additions include:

Charlotte

Edenton

Greensboro

High Point

Lexington

Milton

New Bern

Raleigh

Rocky Mount

Salem

Salisbury

Wadesboro

Wilmington

Winston

Winston-Salem

If you want to see all of the newspapers we have available on DigitalNC, you can find them here. Thanks to UNC-Chapel Hill Libraries for permission to and support for adding all of this content as well as the content to come. We also thank the North Caroliniana Society for providing funding to support staff working on this project.

This holiday season join us here on the blog for the 12 Days of NCDHC. We’ll be posting short entries that reveal something you may not know about us. You can view all of the posts together by clicking on the 12daysofncdhc tag. And, as always, chat with us if you have questions or want to work with us on something new. Happy Holidays!

Day 3: We’ll Come to You

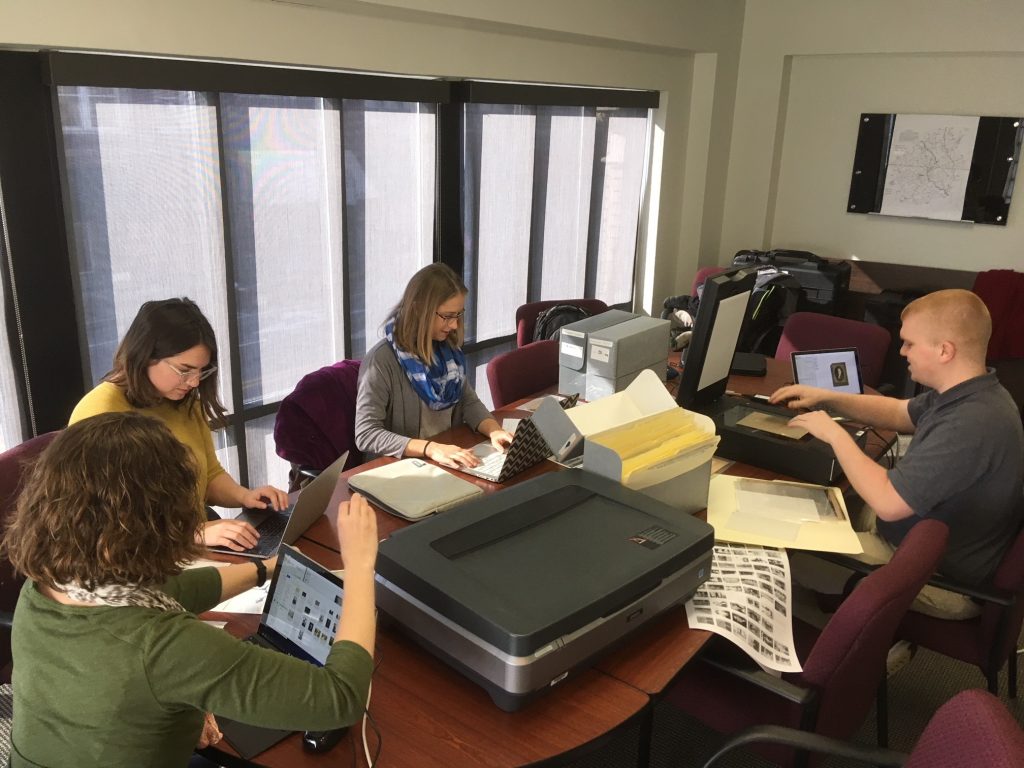

In 2017 we introduced a new initiative – DigitalNC on the Road! in which we pack up our scanners and laptops and travel to partners to scan items in their collections. One of our favorite parts of being part of the NCDHC is getting to see our partners’ institutions (and get in a little NC sightseeing and tasting too!)

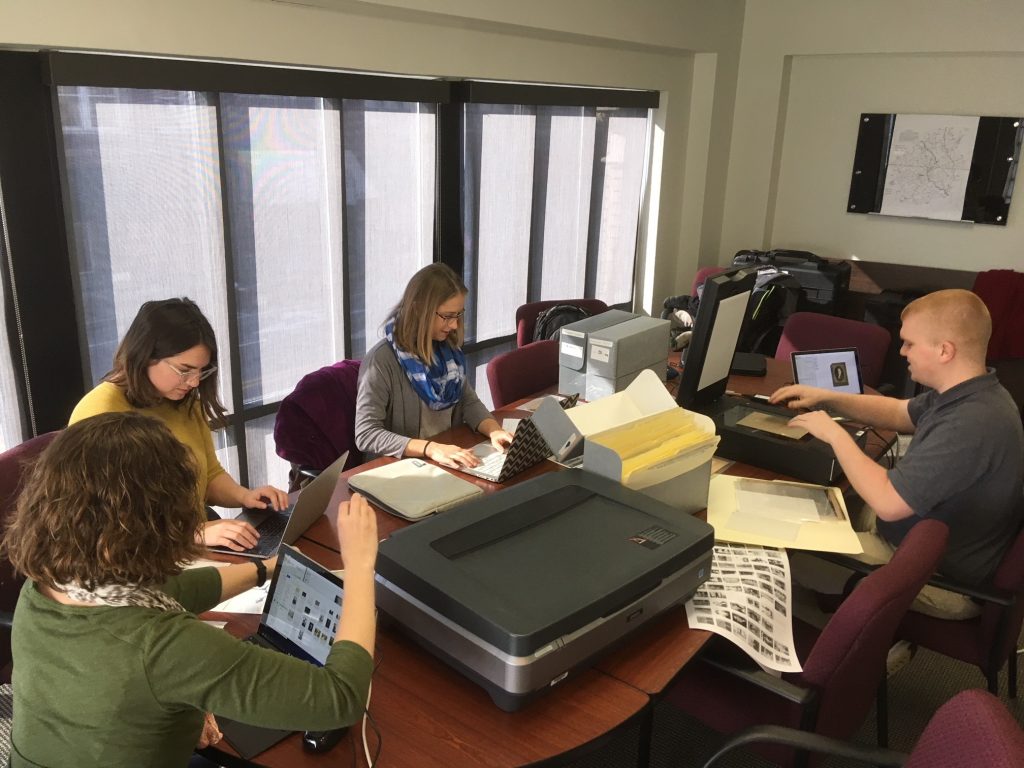

NCDHC staff scanning at Johnston County Heritage Center

Several partners so far have taken us up on the offer including City or Raleigh Museum, Johnston County Heritage Center, Winston Salem African American Archive, Gaston County Public Library and Graham County Public Library.

The length of time we will come for is flexible. Some partners we just visit for a day, other partners we come to for two or three days to really work through a collection. The process to visit starts at least a month beforehand where we meet with you via the phone to discuss what collections we can work on, how many materials we can get through, and discuss initial metadata needs. As far as resources needed once we arrive – a few tables and chairs and outlets near those tables is really it. We have been in community rooms, board rooms, and research rooms for our scanning setups! We welcome the public to view us and ask us any questions they might have. Our blog post announcing the initiative gives a good overview of how the process works. We have done photograph collections, news clippings, student history projects, and slides as part of our on site visits. Starting in January however we’ll have new scanners that will also allow us to easily do bound materials, including yearbooks.

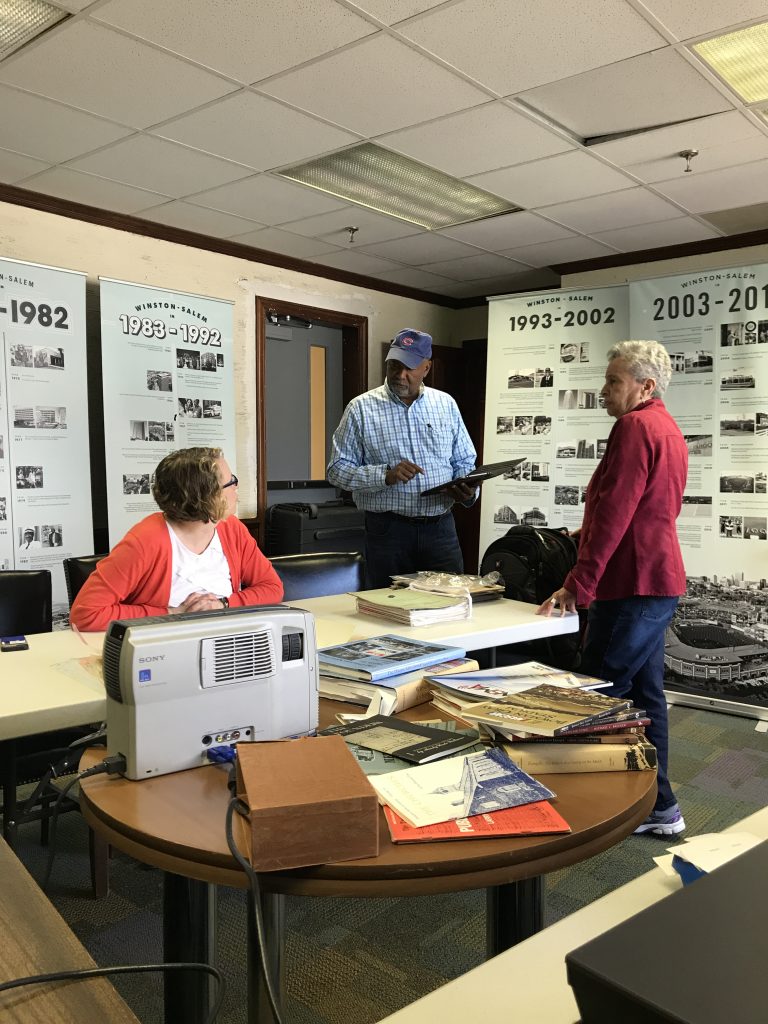

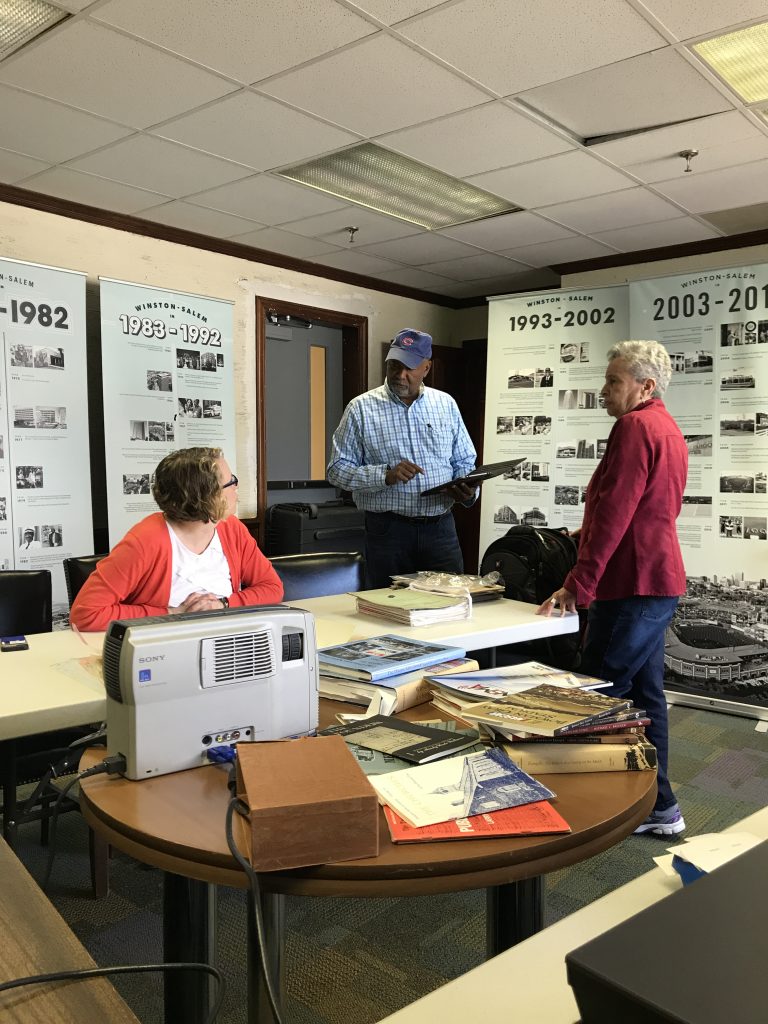

Lisa chatting with board members from the Winston Salem African American Archive

We are also happy to come visit and just talk through the collections you have and what might be candidates for digitization back at NCDHC in Wilson Library, and if you’re ready, take some of those materials back for us.

If you’re interested in talking with us to set up an on site visit let us know. We’re always up for a road trip across North Carolina!

Check back on Wednesday as we reveal Day 4 of the 12 Days of NCDHC!

About two years ago, we had the honor of hosting a group of students from Wilmington who were studying one of the most politically and socially devastating moments in the state’s history–the Wilmington Coup and Race Riots of 1898. Their efforts centered around locating and studying the remaining issues of the newspaper at the center of that event, the Wilmington Daily Record. Owned and operated by African Americans, this successful paper incited racists who were already upset with the political power held by African Americans and supporters of equality. During the Coup, the Record’s offices were burned and many were killed. Thanks to these students, their mentors, and cultural heritage institutions, you can now see the seven known remaining issues of the Daily Record on DigitalNC.

Our main contact on this project has been John Jeremiah Sullivan, a well known North Carolina author and editor. He originally approached us back in 2017 to enlist our help and, since then, has been working with a cohort of supporters, volunteers, and students to dig deeper into the Daily Record and to raise further awareness of its history. Today we’re excited to share the Project’s latest efforts in Sullivan’s own words below.

Daily Record Project Historians, taken by Harry Taylor in May 2017 at the Cape Fear Museum

Highlights

- Over the past few years, Wilmington middle school students have been combing through newspapers, periodicals, manuscripts, and other publications contemporaneous with The Daily Record searching for content from the Record that is quoted in those sources.

- Their efforts yielded numerous quotes, which have been assembled into what they’re calling a “Remnants” issue of the Record.

- Literary content, biographical information about the Record’s editors, Wilmington political news and more can be found in this issue.

- For the first time in one place you can read content that was published in issues of the Record that may no longer exist.

The Daily Record Project

by John Jeremiah Sullivan

“For the past four years, Joel Finsel and I, in conjunction with the Third Person Project, have been meeting weekly with groups of Wilmington 8th-graders to learn as much as we can about the Wilmington Daily Record, the African American newspaper destroyed at the start of the race massacre and coup d’état that turned Wilmington upside down in November of 1898. At the heart of the original Daily Record Project was an attempt to locate any surviving copies of the paper. Books and essays about the massacre always include a sentence along the lines of, ‘Sadly no copies remain,’ but it seemed impossible that they could all have disappeared. After three years’ hunting, we were able to identify seven copies–three in Wilmington, at the Cape Fear Museum (the staff historian there reached out to make us aware of their existence), three at the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, and one at the State Archives of North Carolina in Raleigh. (The latter is a mostly illegible copy of the issue containing Alex Manly’s editorial of August 18, 1898, the article seized on by white supremacists as a pretext for stirring up race-hatred in the months before the massacre.) These seven copies, thanks to the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center, can now be examined online by anyone with an Internet connection. For the first time in more than a hundred years, it is possible to read one of the most famous and important African American newspapers of the late-nineteenth century.

“When those seven copies had been thoroughly read through and annotated, and it did not seem that any more were going to surface (at least not in the near future), we found ourselves faced with the question of “What next?” Should we discontinue the project? We had no desire to do that—it had been too much fun and we were learning too much. We had developed rewarding relationships with the three middle schools that sent their students to study with us: Williston School, D.C. Virgo Preparatory Academy, and the Friends School of Wilmington. The Daily Record Project had become a kind of field laboratory for excavating more information about the events of 1898 and Wilmington history more largely. The last thing we wanted was to shut that down.

John Jeremiah Sullivan addressing the Daily Record Project class at DC Virgo Preparatory Academy, 2019

“We had noticed, in the course of studying the seven copies, that there did exist, in various sources from that period, isolated fragments of text from various issues of the Record that may no longer exist. We were finding these fragments in other newspapers. Just as publications do today, papers were reprinting one another’s material. Sometimes it was in the form of a quotation—several paragraphs, or even just a sentence. Sometimes whole articles were being re-published. In a couple of cases, the text survived by way of advertisement: a traveling circus, for instance, had liked what the Record said about it when it passed through Wilmington, and used that paragraph in announcing future appearances. We started wondering how many of these “ghost” stories might exist. The more we looked, the more we found. We enlisted the 8th graders to help us search. They turned up even more stuff. The range of sources we were using expanded. From old newspapers we moved on to magazines and books and pamphlets and letters. Often the writers or editors doing the quoting were critical of, or even hostile to, the Record and its politics. In attacking pieces from the Record that had offended them, they were unwittingly preserving more of that newspaper’s copy for future generations.

“By the time it was over, we had a folder containing scores of these “remnants,” as we were calling them, enough to create an entire new issue–a “ghost issue”–of the Daily Record, and that is what we have done.

“To create the actual issue, we worked with a brilliant graphic designer in New York named Stacey Clarkson James, who for many years had been the Art Director at Harper’s Magazine. I had worked with Stacey at Harper’s many years ago and have collaborated with her many times since. She exceeded even our high expectations by designing a newspaper issue that is not so much an imitation of the original Daily Record as a resurrection. She went in and crafted, by hand, a typeface that matches the now-extinct one used by Alexander Manly and the original editors. Then she laid out the pages according to the old 1890s press-style, even dropping in advertisements that we knew to have appeared in the Record. At the top it says REMNANTS. We gasped when we saw it.

“On the second page, above the masthead, can be seen a list of sources we used. There are a lot of them. The very size and range of the list shows the scope of the Record’s notoriety in its day. It was being read in many parts of the country.

“Maybe the most interesting thing about this issue is that, because it consists only of material that other publications found interesting enough to re-print, it winds up forming a kind of Greatest Hits compilation (though all of these “hits” have been buried in other papers until now). It’s a fascinating issue to read. There are articles on politics, culture, and social life, as well as strange unplaceable pieces, like the one about a man in Arkansas who caught fire in his orchard and just kept burning. No one could put him out. We still aren’t sure what that one means.

“Two of many things worth highlighting within the “Remnants” issue:

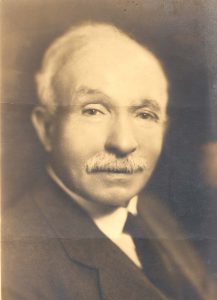

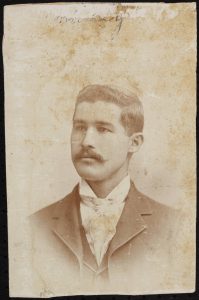

Charles W. Chesnutt, Charles Chesnutt Collection, Fayetteville State University Library.

“First–at the center of the issue is Charles Chesnutt’s short story, “The Wife of His Youth.” Chesnutt was, of course, one of the first great African-American fiction writers, and the novel that many consider to be his greatest work, The Marrow of Tradition, is a re-telling of the events of 1898, set in a fictionalized Wilmington that he calls Wellington. Chesnutt had many and deep ties to this city, more than most scholars are aware. (His cousin, Tommy Chesnutt, was the “printer’s devil” or apprentice at the Daily Record–you can find his name on the masthead on page 2.) “The Wife of His Youth” is probably Chesnutt’s best-known story. What’s curious is how we learned that it ran in the Daily Record. In Chesnutt’s published correspondence, there is a letter to Walter Hines Page, his editor at the Atlantic Monthly. It’s basically a letter of complaint: Chesnutt is telling Page that Alex Manly had reprinted the story (serially) in the Record, without having asked permission. At the time of that writing the Record had already been burnt and Manly had fled Wilmington, so Chesnutt essentially says, I guess we can give him a pass… But the complaint contained valuable information, because it tells us that the Record had an ongoing literary dimension. Manly was likely running stories and poems quite frequently—one of the seven surviving copies also contains a short story, “The Gray Steer” by one Frank Oakling. It’s on page 3 of the August 30th, 1898 issue.

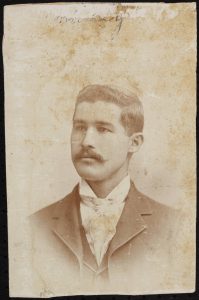

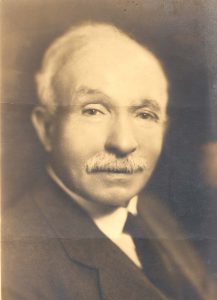

Alexander Manly, in the John Henry William Bonitz Papers #3865, Southern Historical Collection, The Wilson Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

“Second–readers will notice that at the end of the “Remnants” issue, in the last couple of columns on the last page, there is a series of articles from not the Wilmington Daily Record but the *Washington* Daily Record. These represent probably the most exciting discovery we made during this most recent session of the Daily Record Project. The way the story of 1898 traditionally gets told, the massacre and coup d’état marked the end of the Manly brothers’ journalistic careers: they left the city, their ambition blighted, and sank into relative obscurity. The reality could not have been more different. It turns out that the Manlys went almost immediately to Washington, D.C., and re-established the Daily Record there. Before a year was out, they had the press up and running. They operated the Daily Record for four more years in the capital, then handed it off to another editor, who ran it for another six or seven. One of their articles included here is a stirring anti-imperialist denunciation of American military intervention in the Philippines. Another describes the renaissance in African-American literary activity that was felt to be happening around the turn of the century. As far as we can determine, these few pieces represent the only extant copy from the *Washington* Daily Record, for its entire decade-long run.

“There is much more worth unpacking, but we want to allow visitors to the NC Digital Heritage Center’s website to have the fun of doing that themselves.

“Long live the Daily Record. Thank you for reading.

“There are a lot of people to thank. First, the incredible 8th-grade students participated in the “Remnants” session of the Daily Record Project. It was a privilege to work with them and be around their energy:

- Ridley Edgerton

- Bella Erichsen

- Dymir Everett

- Love Fowler

- Malakhi Gordon

- Heaven Loftin

- Katy McCullough

- Juan Mckoy

- Shalee Newell

- Isis Peoples

- Nakitah Roberts

- Gabe Smith

- Maria Sullivan

- Latara Walker

- Ramya Warren

“Second, the adults (teachers, administrators, chaperones, donors, friends, and Third Person Project members) who contributed every week to making this year’s work possible:

- Rhonda Bellamy

- Dan Brawley

- Laura Butler

- Stacey Clarkson James

- Michelle Dykes

- Clyde Edgerton

- Brenda Esch

- Joe Finley

- Cameron Francisco

- Sabrina Hill-Black

- Mariana Johnson

- Trey Morehouse

- Tana Oliver

- Donyell Roseboro

- Elliot Smith

- Beverley Tetterton

- Larry Reni Thomas

- Candace Thompson

- Leyna Varnum

- Tony Ventimiglia

- Florence Weller

- The Cape Fear Museum

- NC State Archives

- The Schomburg Center

“And finally, a shout-out to the Digital Heritage Center. Thanks to you, more than 120 years after white supremacists tried to erase the Daily Record, people are reading it again.”

We love hearing about ways that materials digitized through the North Carolina Digital Heritage Center have impacted research and recreation. We thought since they have done such a great job highlighting us, it’d only be fair to turn around and highlight a few we’ve found recently.

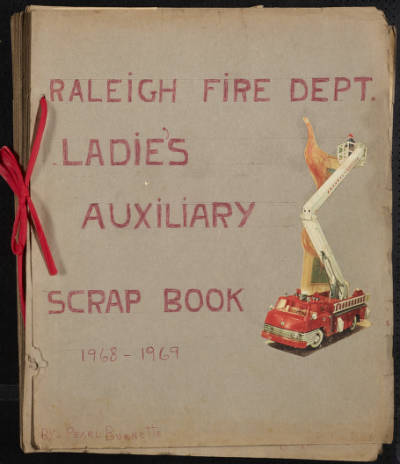

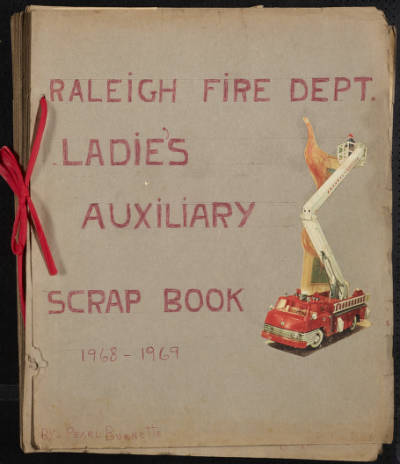

Cover page of the Raleigh Fire Department Ladies’ Auxiliary 1968-1969 scrapbook, digitized for the Raleigh Fire Museum

Our focus today is a particularly fun one because the author of the blog is not only a heavy user of DigitalNC, but also our main contact for one of our partners, the Raleigh Fire Museum. Mike Legeros’s Fire Blog provides a very detailed look into the history of fire departments in North Carolina, as well as keeping up to date on what’s going on in those departments today. It also links to a Fire History page, which has resources of the history of fire departments across the country, including historic and present day photographs of fire stations.

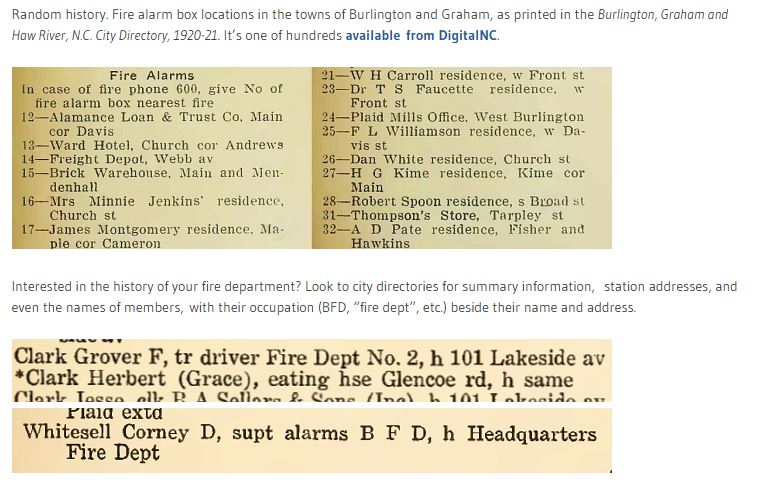

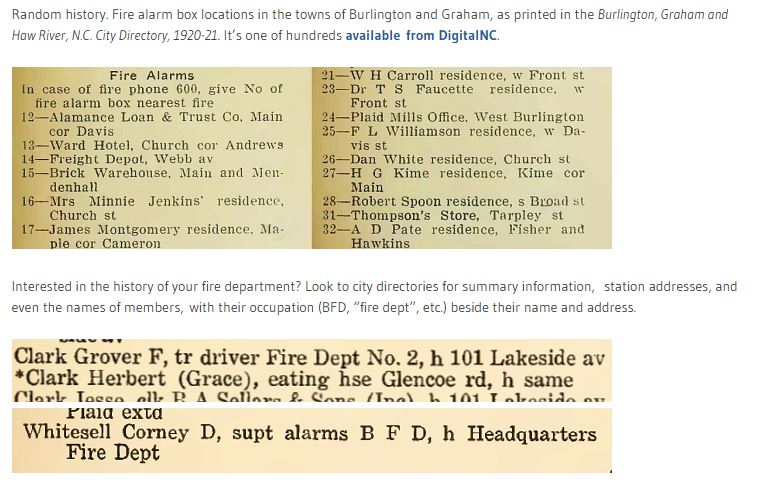

We are particular fans of the post that explains in great detail how to use our city directories, which is one of our favorite resources on DigitalNC and one that Mike has used extensively in his research. You can check out his tips and tricks here: https://legeros.com/blog/burlington-and-graham-fire-alarm-box-locations-1920-21/

If you have a particular project or know of one that has utilized materials from DigitalNC, we’d love to hear about it! Contact us via email or in the comments below and we’ll check out. To read about other places on the web that feature content from DigitalNC, check out past blog posts here.

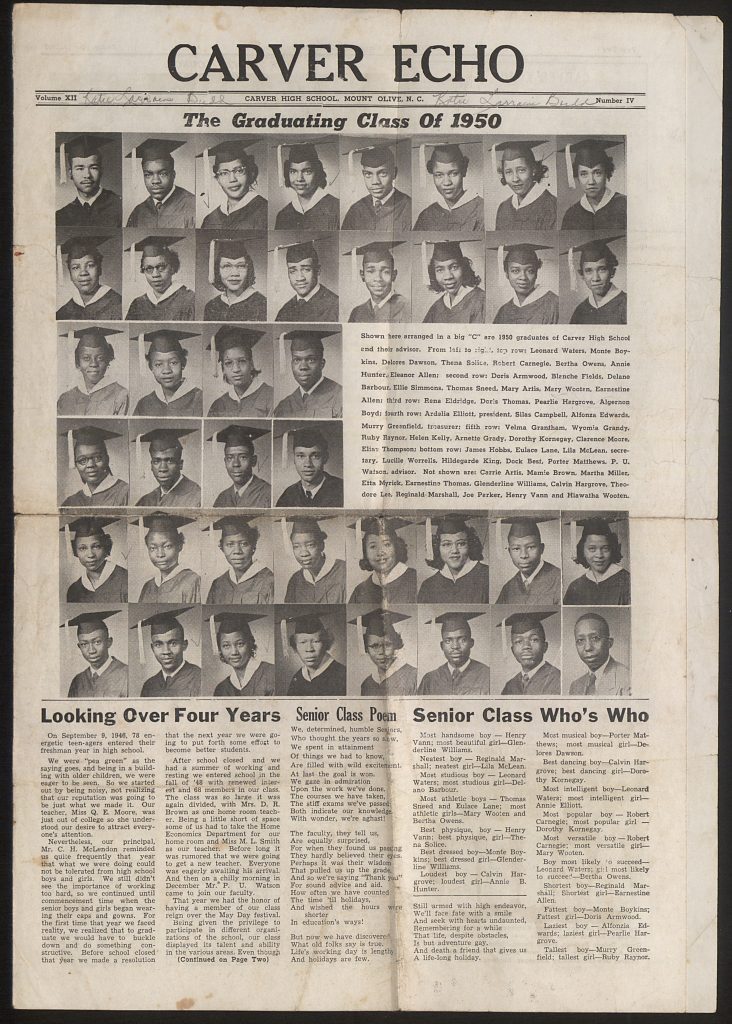

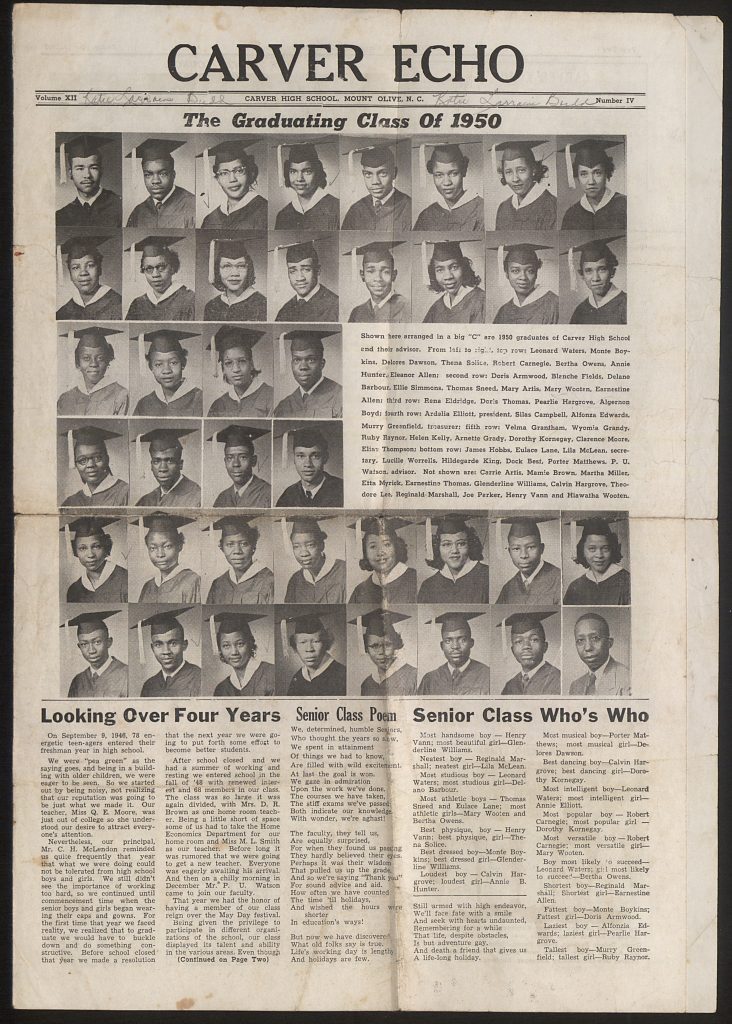

The only issue we have (so far) of a Carver High School newspaper. Mount Olive, NC, May 1950.

From our estimation, DigitalNC shares more digitized historical North Carolina African American newspapers than any other source. Contributors range from our state’s HBCUs to local libraries and museums. To help pull these titles together, we created an exhibit page through which you can search and browse eleven community papers and nine student papers. There are also links to more available on other sites.

Below we’ve re-posted the essay from the exhibit, giving you a brief history of these papers. We hope that we’ll hear from others who may be interested in sharing more of these rare resources online.

~~

Since the publication of Freedom’s Journal in 1827 in New York City, African American newspapers have had a long and impactful history in the United States. Begun as a platform to decry the treatment of enslaved people, the earliest African American newspapers appealed to whites, who were politically enfranchised. After the Civil War, as newly freed African Americans claimed the right to literacy, the number of African American newspapers around the country grew exponentially and the editors began addressing Black people instead of whites. Papers turned their focus from slavery to a variety of subjects: religion, politics, art, literature, and news as viewed through the eyes of African American reporters and readers. Communication about Black political and social struggles through Reconstruction and, later, the Civil Rights movement, cemented newspapers as integral to African American life.

In North Carolina, the first African American papers were religious publications. The North Carolina Christian Advocate, which appears to be the earliest, was published from 1855-1861 by the North Carolina Conference of the Methodist Episcopal Church, followed by the Episcopal Methodist, a shorter-lived publication produced during the Civil War by the same organization. After the Civil War, the number of African American newspapers continued to grow in North Carolina, reaching a peak during the 1880s and 1890s with more than 30 known titles beginning during that time.

The longest running African American paper established in North Carolina is the Star of Zion, originating in Charlotte in 1876 and still being produced today. Other long-running papers in the state include the Charlotte Post (begun 1890), The Carolina Times (Durham, begun 1919), the Carolinian (Raleigh, begun 1940), Carolina Peacemaker (Greensboro, begun 1967), and the Winston-Salem Chronicle (begun 1974). Many of these long running papers powerfully documented Black culture and opinion in North Carolina during the 1960s-1970s, with numerous editorials and original reporting of local and national civil rights news.

Occasionally overlooked sources for African American newspapers are North Carolina’s Historically Black Colleges and Universities (HBCU) and, before integration, African American high schools. You’ll find links on DigitalNC to newspapers from eight of North Carolina’s twelve current and historical HBCUs as well as two African American high schools.

While many African American newspapers have found their way into archives and libraries, it’s common to see broken runs and missing issues. You can find a great inventory of known papers from the UNC Libraries. If you work for a library, archive, or museum in North Carolina holding additional issues and would like to inquire about digitizing them and making them available online, please let us know.